New year brings accolades to history department

Campus historians pick up impressive number of AHA honors

January 2, 2019

A “bumper crop” of prestigious awards, prizes and honors will be presented tomorrow (Wednesday, Jan. 3) in Chicago to UC Berkeley faculty members by the American Historical Association, the nation’s most important professional association for historians.

Two history professors — Peter Sahlins and Yuri Slezkine — have won book awards, history professor emeritus Martin Jay has earned a lifetime achievement award and the California History-Social Science Program, which has a branch in Dwinelle Hall, is receiving a prize for distinguished K-12 history teaching.

“Competition can be fierce,” says Department of History chair Peter Zinoman, of the annual AHA awards. “It’s not unusual for Berkeley historians to win one, or maybe two, AHA awards during a single year, but four is truly a bumper crop.”

The 2018 AHA awards were announced in October, but will be handed out this week at the AHA’s 133rd annual meeting, which runs from tomorrow to Saturday. The prizes cover exceptional books, distinguished teaching and mentoring in the classroom, public history and other projects. The finalists were chosen from a field of more than 1,500 entries.

Louis XIV’s animals, Bolshevism’s rise and fall

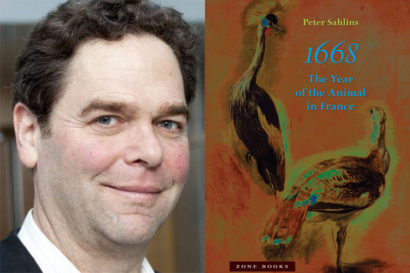

Peter Sahlins, who also is director of Berkeley’s Interdisciplinary Studies Field, has won the J. Russell Major Prize for the best work in English on any aspect of French history for 1668: The Year of the Animal in France (Zone Books, 2017). He says 1668 was “a remarkable year in France, when animals and their symbolic representations ― in literature, in art, in medicine, in philosophy and especially in politics ― helped transform the French state and culture.”

Peter Sahlins won an AHA award for his book 1668: The Year of the Animal in France.

He became interested in the subject while noticing an unusual and understudied convergence of texts and projects during Louis XIV’s early reign in France (1661-1715), when French culture appeared to be swerving away from its Renaissance past toward modernity.

So many of the writings, tapestries, illustrations and academic lectures that Sahlins found concerned the Royal Menagerie in the gardens of Versailles, where exotic and peaceful birds from around the world were housed, and “involved the figure of the absolute monarch in relation to animals,” as well as the kinship of humans and animals, says Sahlins. “And at the same time, in and after 1668, French intellectuals and artists engaged with the writing of René Descartes and his mechanistic understanding of animals.”

Sahlins, who calls 1668 an “animal moment,” says he also discusses in the book how different symbolic representations of animals “augured a new era in the conception of animals that tends to devalorize and naturalize them, but also us, as humans. It marked the passage from ‘we, including animals’ to ‘we are animals,’ a debasement of the human that is part of the making of the modern subject.”

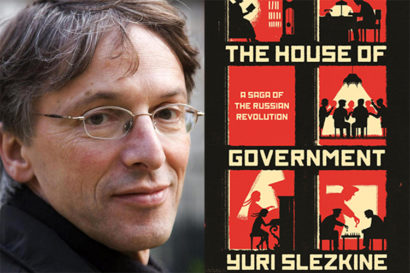

Yuri Slezkine’s book The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution was awarded the AHA’s George L. Mosse Prize.

Yuri Slezkine, the Jane K. Sather Professor of History, will receive the George L. Mosse Prize for an outstanding major work of extraordinarily scholarly distinction, creativity and originality in the intellectual and cultural history of Europe since 1500 for The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution (Princeton University Press, 2017). An epic that runs more than 1,000 pages, the book tells the true story of the top Communist officials and their families who lived in Moscow in the enormous House of Government — later called the House on the Embankment — and “who ruled the Soviet state until some 800 of them were evicted from the House and led, one by one, to prison or their deaths,” says Slezkine. Completed across the Moscow River from the Kremlin in 1931, the 505 furnished flats, along with public spaces that included everything from a movie theater and a library to a tennis court and a shooting range, made up the largest residential building in Europe.

The book draws upon diaries, letters, autobiographies and interviews and includes hundreds of rare photographs.

Zinoman calls the book awards for Sahlins and Slezkine “bittersweet.”

“They confirm what we already know — the brilliance of these colleagues,” he says. “But they also remind us of the sad news that both Peter and Yuri have announced that they plan to retire at the end of the year.”

Lifetime achievement, top K-12 teaching

Martin Jay, Berkeley’s Sidney Hellman Ehrman Professor of History Emeritus, is one of three scholars receiving the AHA Award for Scholarly Distinction, which honors senior historians in the United States. The award has been given since 1984, and 77 scholars have received it. The other 2018 winners are Charles Maier of Harvard University and Nell Irvin Painter of Princeton University.

Martin Jay, Berkeley’s Sidney Hellman Ehrman Professor of History Emeritus, will be presented with the AHA Award for Scholarly Distinction, which honors senior historians in the United States.

During Jay’s 45-year career at Berkeley, the AHA says he “transformed the study of French and German intellectual history and critical theory. His work is known to historians around the globe, and his scholarship from the 1970s onward is still widely read for its extraordinary erudition, its methodological innovativeness and its clarity of exposition.”

Jay is the author of nine books — some translated into as many as 10 languages, five edited volumes and more than 100 articles. He has received major awards, visiting professorships and invitations to lecture all over the world. The AHA credits him with training “many of the leading intellectual and modern European historians teaching today” as well as with shaping the work of Berkeley graduate students in many disciplines. In October 2016, Jay was celebrated at a conference at Berkeley at which all 31 speakers had had Jay as their primary doctoral studies adviser and were working at universities — in history as well as in law, journalism and public policy — in the United States, Europe, Asia and Australia.

Jay also helped develop Berkeley’s interdisciplinary program in critical theory.

Also at the AHA meeting, the Beveridge Family Teaching Prize for distinguished K–12 history teaching will be presented to the California Department of Education and the California History-Social Science Project (CHSSP), which is headquartered in UC Davis’ Department of History, but has one of its six regional sites at Berkeley.

Established in 1995, the prize recognizes excellence and innovation in elementary, middle school and secondary history teaching, including career contributions and specific initiatives. The prize is awarded on a two-year cycle rotation: in even-numbered years, it goes to a group; in odd-numbered years, to an individual.

At each regional site, teachers and scholars work together to improve classroom instruction, student learning and literacy. Berkeley’s CHSSP website describes “a special focus on meeting the needs of English learners, native speakers with low literacy and students from economically disadvantaged communities.”

Brewer Prize joins the mix

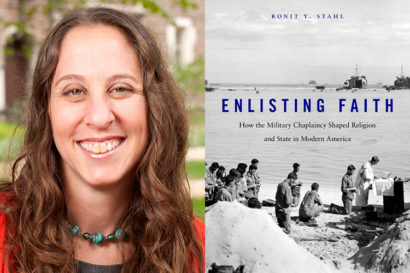

Ronit Stahl, assistant professor of history, is receiving the Frank S. and Elizabeth D. Brewer Prize from the American Society of Church History for her book Enlisting Faith: How the Military Chaplaincy Shaped Religion and State in Modern America. (Washington University in St. Louis photo by Sid Hastings)

An additional Department of History faculty member, assistant professor Ronit Stahl, is receiving a highly regarded prize this week from the American Society of Church History (ASCH) for her book Enlisting Faith: How the Military Chaplaincy Shaped Religion and State in Modern America (Harvard University Press, 2017). The Frank S. and Elizabeth D. Brewer Prize honors outstanding scholarship in church history by a first-time author.

The ASCH awards will be presented at the society’s winter meeting, which also is being held this week in Chicago.

Her book examines the growth and development of the military chaplaincy, from World War I through the late 1980s, and its impact on American life. Initially, only Protestants and Catholics were in the chaplaincy’s ranks; today, they also include Jews, Mormons, Muslims, Hindus and individuals of many other faiths. Stahl also writes about the federal government’s role in authorizing and managing religion in the military.