Robert Alter sets a new literary tone with his translation of the Hebrew Bible

After a quarter century of work, the UC Berkeley scholar is starting to draw some rave reviews with the just-released three-volume, 3,000-page tome.

January 18, 2019

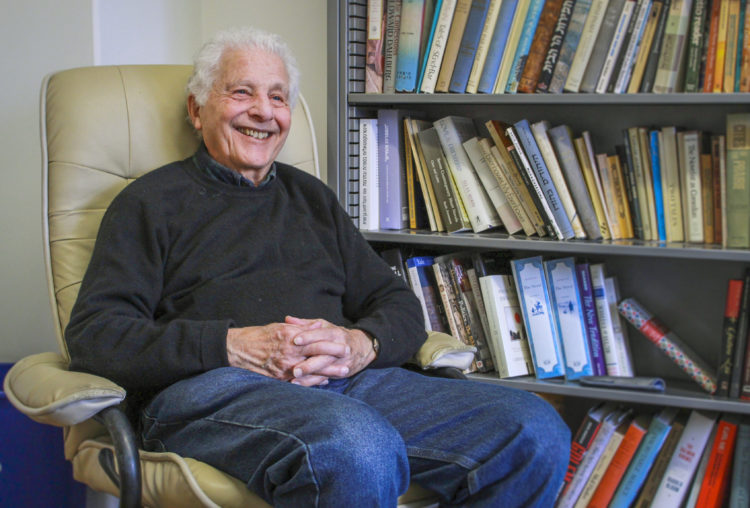

Robert Alter needed a quarter of a century, but his translation of the Hebrew Bible is garnering praise. (UC Berkeley photos by Jeremy Snowden)

There aren’t many stories surrounding the Bible that begin with Czech novelist of the fantastic Franz Kafka, but Robert Alter’s does.

Alter was already 25 years into his career teaching comparative literature and Hebrew at UC Berkeley in the mid-1990s when a representative of the publishing house W.W. Norton approached him about ideas for his next book.

“He proposed I’d do a book for Norton in their Norton Critical Series,” Alter says. “He said maybe something from Kafka or maybe something from the Bible. And not watching my lips, I said, `Well, somebody could make a really neat Norton Critical Series edition on the Book of Genesis, because there are now many good materials that you could include with the text of the book.’ But the problem is that there is something wrong with all the existing translations.”

Come again? The Bible has been in almost continual translation for better than 2,000 years and there’s something wrong with all those translations?

That statement sounds a bit ludicrous, but given language differences and the way language changes over time, there are always going to be thoughts that don’t jump easily from one to another. The Bible, being written by many people over a thousand-year stretch that ended about 165 B.C., is galactically difficult to translate.

“So, I said if I were to do this, I would have to do my own version,” Alter says, “my own translation.”

And that’s why he was tempted to dive into Kafka, of whom he is a huge fan and about whom he’d already written. In the end, however, he agreed to write an English translation of the Book of Genesis, something he said he figured would be a one-and-done. Wrong. He never stopped working on the Bible. And a quarter of a century later, he’s just published The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary, a new look at the Old Testament.

Robert Alter

His initial translation of Genesis surprised Alter with its popularity, enough so that he took a stab at translating the David story. At that point he was hooked, sort of. He thought he’d come back with “a nice little volume” centered around the books of Ruth and Esther, but his agent, Steve Foreman, said that from a publishing business perspective, there wasn’t much there there.

“And I asked, `Steve, what do you have in mind?’ And he said, `If we had our druthers, we’d love you to do the whole Hebrew Bible.’ And I immediately said, `Give me a break.’ So, I discouraged him, and we settled on the five books of Moses.”

Foreman ultimately won out. It wasn’t apparent that he would, though, until the last four years. It was four years ago that Alter came to the realization that he was already two-thirds of the way through the Old Testament, and, after taking a deep breath, plunged into dealing with the final one-third.

“The way I work in translating, it’s not something you do for eight hours a day,” Alter says. “So I’d work for three or four hours, and I’d translate a dozen verses or 15 verses and I’d be done. And then I’d go back the next day, look it over and continue. So I made progress that way. When I realized I’d done almost two-thirds, what I had to look at hard were the Prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah and so forth.

“That’s a huge amount of material — easily double the length of the five books of Moses. And it’s challenging. There are textual problems, there’s great poetry that you’re going to have to try to get into English. I said I figure I can do this now.”

Alter says he became literate in Hebrew when he was about 15 and read the Hebrew Bible in full for the first time when he was 18. He spent much of the early part of his scholarly career, however, on modern novels. Including Kafka, whose works drove many a college student bonkers.

Over the last 24 years, Alter has balanced his work on the modern novel with time spent translating the Old Testament in a way that strikes him as “rhythmic.”

“What I’ve tried to do is to reproduce the beautifully expressive syntax of the Hebrew, which the modern translators don’t try to do at all,” he says. “They try to make it read like yesterday’s newspaper. And then there’s the matter of sound play and word play, beginning with rhythm.

“Now, obviously the poetry has a certain rhythm, but I think the prose does, too. All great literary prose is rhythmic. And if you translate as arrhythmic, you are destroying the effect of the original. So that’s the kind of thing that I’ve worked on. And I think that is quite different from the English versions that have been produced by all these committees.”

Alter isn’t alone in feeling that. His new work has much buzz behind it. The New York Times Magazine says the finished work rivals the 1611 King James Bible. That’s heavyweight caliber competition.

Other early reviews of the work have been similarly laudatory, and some have pointed out that Alter’s translation is literary rather than scriptural.

“I can accept that, with this reservation — I think the scriptural is literary,” Alter says. “For reasons that we can’t quite fathom, in this rather provincial little kingdom sandwiched between the big empires of the ancient Near East, there were writers of genius. And they chose to cast their religious vision in great narratives and at times magnificent poetry. So, it is my contention that to get to the subtleties and sometimes to the heart of their religious visions, you have to try to represent the literary vehicle as well.

“To some extent it’s done in the King James version. They (47 17th century Church of England scholars) had a very good sense of English style, unlike the 20th century committees, people with Ph.D.s in the Bible from Yale and Harvard and Oxford and Cambridge. The King James translators were very much in touch with the literary culture of their age, so it’s not surprising that they could produce great effects of eloquence. But it’s uneven. There are many lapses.”

Alter says that “in order to keep myself sane” he tried to spend only about four hours per day on translation. Using the standard version of the Hebrew text that scholars and synagogues favor, he was able to translate close to 100 percent of the Bible that way over the course of more than two decades.

But every so often he’d come across a word or phrase that “didn’t sound quite right.” That’s when the process became most arduous.

Particularly troublesome, he says, was one of his favorite Biblical books, Job.

“I loved translating Job. I think it is among the most amazing poetry to come out of the whole ancient world,” Alter says. “It’s quite amazing. So first there is the question of how do you do justice to this beautiful poetry from a whole other language. But that was kind of an enjoyable challenge.

“The other challenge was that I’m afraid that scribal transmission has badly messed with the text of Job. There are many places where there are things that are not quite comprehensible. You have to struggle with `What am I going to do about this?’”

He struggled through, and now the three-volume set, comprising 3,000 pages, is out there, available at your local bookseller, just like Kafka.