Couple builds bridge to Berkeley for Coachella Valley’s brightest, neediest youth

For years, Luisa and Oscar Armijo have been inspiring and helping high-achieving teens from low-income families in the faraway agricultural area to succeed here

January 24, 2019

Hilda Zarate-Cervantes badly needed a champion. It was March 2015, and the high school senior had just landed an in-person interview for a coveted UC Berkeley scholarship that, for her, would mean a full ride.

Zarate-Cervantes lived in Thermal, a rural, desert community in Southern California’s Eastern Coachella Valley. When she, her mother and five siblings lacked rent money, they’d share one room in her uncle’s un-airconditioned trailer. Their old car wouldn’t survive the three-hour drive to the interview in San Diego.

“I was one in 2,000 students invited, and only 100 are selected for the award. I needed that interview to have a chance to afford college, so I wouldn’t have to say goodbye to my dreams,” says Zarate-Cervantes. “I looked around for a ride. The principal said he couldn’t help. It was very stressful.”

Panicked, she turned to Luisa Armijo, who along with her husband, Oscar, is known in the valley for inspiring and helping high-achieving teens from low-income families to attend Berkeley. Armijo phoned Desert Mirage High School, educating officials there about the scholarship’s prestige and threatening to tell the media if no one helped.

Zarate-Cervantes and her mom soon were on their way, the school registrar at the wheel.

“I thought I’d have the same future as many young people here, but Luisa believed in me,” says Zarate-Cervantes, 21, who received the Regents’ and Chancellor’s Scholarship, a merit scholarship that fulfills financial need, and today is a law school-bound Berkeley senior. “She said she and Oscar would be there for me every step of the way.”

About half of the mostly Latino residents In Eastern Coachella Valley — one of the world’s top agricultural regions that’s especially famous for its date crops — are at the poverty level, primarily work in the fields and in low-wage service industry jobs and have less than a ninth-grade education.

The Armijos have lost exact count, but in the past 20 years, they’ve helped shepherd about 100 young people to Berkeley from Coachella Valley, a 45- by 10-mile area that includes Eastern Coachella Valley and its four main unincorporated communities: Thermal, Mecca, Oasis and North Shore — population 25,000.

In the eastern valley, the tireless activists and philanthropists primarily target Coachella Valley and Desert Mirage public high schools. They promote Berkeley, network with high school counselors, help teens navigate the college application process, befriend and educate parents reluctant about college — especially one 500 miles away — and help Berkeley admits in need with scholarships and dorm essentials.

“Luisa and Oscar are like the aunt and uncle you can always rely on,” says Fausto Figueroa, 22. In Thermal, he and his eight siblings were raised by their grandparents, who pick grapes, because of his parents’ drug addiction. Without the Armijos, he adds, “I would have been a statistic.” Instead, Figueroa entered Berkeley as a Gates Millennium Scholar and graduated last month with a degree in Chicano studies. Next, he plans a master’s degree in education.

Jesus Perez, an academic adviser at Coachella Valley Adult School, calls the Armijos “champions of educational justice” who see brilliance and hope in an isolated, underresourced and often-overlooked area of California.

“We believe in the potential in everyone,” says Oscar Armijo. “But it takes access to opportunities to change your life, to open doors so that great things can happen.”

The stark divide

Luisa and Oscar Armijo live on the other side of Coachella Valley, the prosperous west, with its luxurious resorts, lush golf courses and hip mid-century modern architecture. Their Palm Desert home is within walking distance of Indian Wells, one of the state’s most affluent cities.

But both Luisa, 63, a social worker, and Oscar, also 63, a certified public accountant, grew up in low-income families and underserved communities. And although Luisa Armijo says that today they could afford to buy “a Tesla, a Mercedes or other things, we choose not to.”

Instead, the humble duo devotes energy and resources to helping academically talented valley youth break the cycle of poverty with an education at Berkeley — a school that, remarkably, the Armijos did not attend.

It was the experiences of their four children — Aiyana, Oscar, Citlali and Chimayó — at Berkeley between 2000 and 2014 that captivated these University of Southern California alumni, who served in Berkeley’s Cal Parents organization for 16 years, two of them as co-chairs. Berkeley’s strong ethic of public service and social justice also matches the Armijos’ family values.

“At Berkeley, our kids just blossomed,” says Luisa Armijo. “Their hands spread wide, and the whole world opened to them.”

The Armijos want the same for students on the other side of the valley’s divide, where the median household income is about $26,000. Many families live in illegal mobile-home parks in poverty-stricken conditions. The eastern valley has made headlines for its environmental and public health perils. And last fall, it was the sole U.S. stop for the Flying Doctors of America, who provide free medical and dental services to uninsured families.

“That’s the only time many people here see a physician or a dentist. They start lining up in the wee hours of the morning,” says Berkeley alumna Rosemary Bautista, who grew up in Coachella Valley. She returned in 2009 as an immigration lawyer who represents low-income clients in the process of applying for their initial lawful permanent residency or to become U.S. citizens, as well as individuals in removal proceedings before immigration federal courts.

In addition to Bautista and a few more attorneys, other Berkeley alumni putting their degrees to use in their Coachella Valley hometowns include physicians, a Superior Court judge, bankers, teachers, city engineers and city managers.

“Going to Berkeley pushes you to build community,” says Bautista. “What better one to build than your own?”

“Poverty is a big problem in the valley,” adds Luisa Armijo. “And education is an important tool for social change.”

The Armijos are proof of that, too.

People of conscience

Luisa Armijo grew up around the Port of Los Angeles, within a neglected, predominantly black neighborhood. She observed the Watts riots of 1965, the lack of schools that adequately prepared students for college, too few quality job opportunities for youth and the violence and drug activity that turned the streets dangerous at night.

Armijo’s Mexican-American parents — her father also had Native American roots — “worked hard to give us a good Catholic school education,” says Armijo. They also gave their four children work and leadership experiences through summer youth programs.

Already at age 13, Armijo says, “I wanted to help my community.” Later, she would earn a master’s degree at USC’s School of Social Work, having defied her Catholic teachers’ predictions that she’d “end up pregnant before I got to high school.” Her career has focused on youth — gang members, pregnant teens, drug addicts, the incarcerated and, for 36 years, Native Americans on Coachella Valley’s Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indian reservation. There, she developed a comprehensive tribal library and a college pipeline program.

“I had a lot of hope for all of them to finish high school, to go to college,” says Armijo of her young advisees. “Everyone wants to succeed, to graduate, to have a better life.”

Oscar Armijo, born in Texas but raised in Mexico, was the first of eight siblings to go to the United States for college. At 17, he traveled alone to live with his aunts in Coachella Valley and to attend community college while juggling four part-time jobs, including harvesting grapes.

“I got exposed to labor conflicts in the fields, to UFW organizing, to picketing and struggles. To poverty. I saw people arrested, oppressed for being Hispanic, Latino,” he says. “I developed a consciousness and got involved in causes, and I felt I needed to go back to my communities and work to help with change.”

After transferring with a scholarship to USC’s accounting school, he met his future wife. They bonded over “working for causes, for organizations that make a change for other people,” he says. They also became salsa-dancing and racquetball partners.

After the pair’s graduation from USC in the late 1970s, Oscar Armijo and peers who’d attended UCLA and Cal State Northridge opened Coachella Valley’s first community health center, which provided free medical services to migrant farmworkers and other indigent populations.

For the past 30 years, Armijo has run a public accounting firm; many of his clients are nonprofit and non-governmental organizations. He’s awarded need-based Oscar G. Armijo CPA Latino Leadership Scholarships for about 20 years to college-bound Latino students from Coachella Valley who demonstrate academic excellence, extreme financial hardship and community involvement.

The Armijos first offered college scholarships in 1999 to students at Palm Desert High School, which their children would attend. But in 2009, at the urging of Larry Salas, who at the time was an academic counselor at Coachella Valley High School and in charge of the school’s scholarship program, they also began assisting Berkeley-bound students in the eastern valley.

“Counselors come to us and recommend students deserving of a scholarship,” explains Luisa Armijo. “Today, we’re also developing relationships with the Coachella Valley Unified School District itself and the board members.”

In addition to need-based scholarships, $500 worth of dorm supplies — a blanket, sheets, towels and more — are given to incoming Berkeley students by the Armijos and Cal Bears in the Desert. Luisa Armijo spearheaded the launch of the 80-member California Alumni Association chapter in 2012.

“A lot of these students would arrive at Berkeley without bedsheets and proper dorm room supplies,” says Bautista, who co-chairs Cal Bears in the Desert with alumnus Moises Moreno-Rivera. “I call Luisa Mama Bear. If a student needs something, Luisa makes sure it gets taken care of.”

So does Oscar Armijo. Maximiliano “Max” Ochoa, 27, a member of the P’urehpecha, an indigenous group from Michoacan, says he got a waterproof jacket in the mail from Armijo his freshman year at Berkeley after Armijo saw him without one in a storm. Ochoa moved with his mother and siblings from Mexico to Thermal in 1998 — his father arrived in the mid-1980s — and his parents still work in the fields. The family used to live in a trailer near the infamous Duroville trailer park that, says Ochoa, “brought national headlines about the living conditions of migrants.”

With help from the Armijos that included a job in high school cataloguing books at the tribal library, Ochoa went on to attend Berkeley and then UC Irvine, where last spring he earned a master’s degree in public policy. The Armijos are “like my second parents,” says Ochoa, and were at both ceremonies.

“The gap Luisa and Oscar breach for first-generation, college-bound students is necessary to navigate college,” he adds. “They are more than a support system and more like family.”

Underserved students don’t just need financial assistance and academic guidance, agrees Julian Ledesma, executive director of Berkeley’s Centers for Educational Equity and Excellence (CE3). “The Armijos understand what it takes to engender a sense of belonging that leads to academic success,” he says, “so they commit a special brand of comprehensive care and support to students from the Coachella Valley. Luisa and Oscar have established a lasting legacy based on familial love.”

“They are people of conscience,” adds Lupe Gallegos-Diaz, director and academic coordinator of Berkeley’s Chicanx/Latinx Academic Student Development Office, which recruits the Armijos to address new students and their families — in both Spanish and English — at its annual Familia Orientation on campus. “They understand the conditions a lot of us come from.”

Fighting for access

Conditions in Eastern Coachella Valley can make it tough just to apply to college.

When the Armijos first began working there, infrastructure for the internet was minimal, most students didn’t have cell phones or laptops, and computer access was only at school. “Gradually, that’s starting to change,” says Luisa Armijo, “but it’s still limited.”

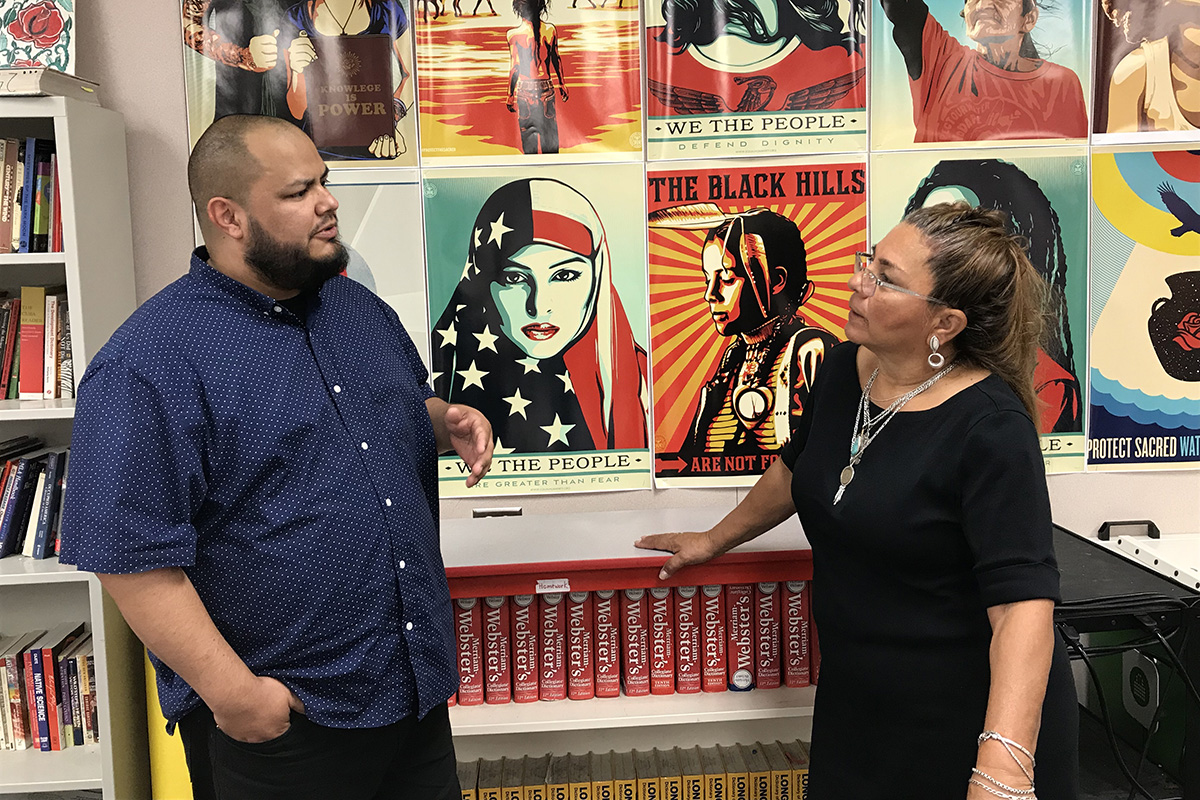

Recent Berkeley alumnus Fausto Figueroa says people ask him, “Is Coachella a fruit?” “It’s a place on the map,” he says, that’s changing as its educated youth return from college. With seven younger siblings there, he adds, “Why wouldn’t I want to go back and make it better for the generation to come?” (Photo by Bill Thornton)

Fausto Figueroa arrived at Berkeley in 2014 without a dorm room; his family couldn’t afford internet access, so he hadn’t received emailed housing instructions. He also couldn’t pay the fee to secure his room — it wasn’t covered by his Gates scholarship. “Fortunately,” says Figueroa, “Luisa reached out to her contacts, and everything got fixed.”

“Networking” is the term Armijo emphasizes to describe her work. She says, “We pull together resources to provide the most support — school counselors, parents, Berkeley alumni, Berkeley staff, local government officials and food and clothing distribution programs.”

Thanks in part to Armijo, the valley’s high school counselors are up to speed on the UC admissions process. But they’re less available to students: Today, there are 500 students for every counselor in Eastern Coachella Valley — a jump from last year, before layoffs, when the ratio was 350 to one, according to district officials.

Also grim is data from the state’s California School Dashboard. At the eastern valley’s three high schools, student progress in English and math is rated low to very low, the graduation rate at two of the schools is low, there are too few college prep courses and more than half the students lag in college/career preparedness.

“We have very limited resources for education, and it’s hard for students to get accepted to four-year (schools),” explains Johnny Gonzalez, a Desert Mirage High School teacher. “We combat apathy, low expectations, the social pressures our students face, loss of hope.”

The district does offer college readiness programs — AVID and, since 2015, the popular Puente Project, which has its headquarters at Berkeley. At Desert Mirage, Gonzalez says 280 students flock to Puente’s curriculum, which aims “to empower and transform students as people of color, to help them utilize the cultural wealth of who they are.”

Another important tool, he says, is Luisa Armijo, who connected Gonzalez to Ebelio Mondragon, assistant director at Berkeley’s Office of Undergraduate Admissions. Mondragon visited Desert Mirage students last fall to explain the UC admissions process and how to be a competitive applicant.

“Berkeley can seem like a very distant land,” says Gonzalez, “but now, our students have greater access to it.”

Connections count

Despite these steps forward, the Armijos and Berkeley desert alumni lost an important tool last spring to promote Berkeley — a popular annual yield event they hosted for new admits and their families at UC Riverside’s Palm Desert campus. The timing of a recruitment strategy change by the California Alumni Association (CAA) and a change in the Office of Undergraduate Admissions’ leadership impacted that outreach effort.

“Many of these families have never seen the campus and can’t afford to travel to Berkeley for Cal Day,” says Luisa Armijo, adding that students she’d hoped would consider Berkeley for 2018-2019 were scooped up by other schools investing more in outreach. “Parents have questions: ‘Where will my child stay? Who will he stay with? How will he eat?’ Most of these parents don’t know what a dorm looks like.”

Sending a child to college, especially a distant one, “is really scary for some parents, especially those who never completed their education,” adds Bautista. “They’re looking forward to their child getting out of high school and just working. Families making below minimum wage, doing seasonal labor, need that extra pair of hands to supplement the family income.”

“When I started as a migrant counselor, there was a good number of Latina students with ideal grade point averages that I encouraged to apply to a four-year university,” says Saul Martinez, academic counselor at Coachella Valley’s Indio High School, “and they’d come back the next day or so and say, ‘I don’t think I can apply. My dad doesn’t want me to go. He thinks I’ll get pregnant and end up with two or three kids.’ I started inviting Latina counselors who spoke the language to parent meetings and, within months, I began noticing the difference. It was transformational.”

“That’s the sort of thing Luisa does,” adds Bautista. “She’s willing to speak to parents, to help them take that leap of faith.”

For many years, Berkeley staff members Ledesma, from CE3, and Fabrizio Mejia, assistant vice chancellor for student equity and success, staffed the UC Riverside Palm Desert yield event. A vital part of the Armijos’ network, they continue to be thought partners with the couple about how to best support first-generation students from the eastern valley. Adds Ledesma, “We’ve committed to the Armijos and admitted students that CE3 will be there for them if they choose Cal.”

Silvia Marquez, Berkeley’s associate director of admissions, says Eastern Coachella Valley families need in-person contact with Berkeley. Chancellor Carol Christ’s recent announcement about the launch of a new Undergraduate Student Diversity Project, which stresses the importance of yield events, holds promise for a renewal of such activity.

“If we aren’t present in this part of Coachella Valley,” says Marquez, “Berkeley may not get on these students’ radar.”

And Berkeley needs students from Eastern Coachella Valley, says Perez, at Coachella Valley Adult School.

“We are an integral part of California, and our students represent that,” he says, adding that he, too, came from a migrant family, one that packed honeydew melons in Bakersfield. “Their narratives are valuable. Their stories can change policy. And the Armijos dare them to dream.”

Creating an extended family

Eight years ago, at Berkeley’s annual Reunion and Parents Weekend at Homecoming, the Armijos noticed that Eastern Coachella Valley students were missing their parents, who typically can’t afford to travel to Berkeley for the weekend of tours, lectures, receptions and football.

“It’s expensive to stay in hotels. They’d have to sleep in their cars,” says Luisa Armijo. Language is another barrier to travel, she adds, as are the fears of the undocumented.

That weekend, the couple took the homesick students to a Mexican restaurant in Berkeley for “the closest they could get to a home-cooked meal,” she says. “We became their parents for the weekend.”

Today, that dinner has grown into an annual tradition — the Desert Student Dinner, a popular mini-homecoming event that the Armijos host each fall near campus for the Berkeley students, staff, faculty and alumni from Coachella Valley and for other staffers whose units provide the students with support.

“We’ve built a family for these students at Berkeley,” says Luisa Armijo, “a network so they won’t be alone, so their parents know they’re not alone.”

“We’re not trying to replace their parents,” she adds. “We’re trying to help them.”

Last November, at Shorb House, home of Berkeley’s Latinx Research Center, the Armijos, their children and a few dozen campus staff and alumni participants greeted nearly 30 Berkeley students with Mexican food; a campus trivia contest; the gift of most students’ first Cal T-shirts and sweatshirts; an alumni advice panel; remarks by Christian Paiz, an assistant professor of ethnic studies with roots in Coachella Valley; and a lecture by Abraham Ramirez, a Berkeley Ph.D. candidate in ethnic studies. Ramirez was a first-generation college student from Coachella Valley whose parents came to the United States from Mexico as farm laborers.

Admiring the full house, Figueroa said, “When I was a freshman, there were 10 or 12 of us who came to this event, and now the whole room is filled up. It’s like home. Like a home away from home.”

During a formal program, wisdom was dispensed to students by members of Berkeley’s community, some of them also from Coachella Valley: Find a mentor. Go to office hours. Ask questions. Get involved in clubs. Explore activities outside your comfort zone. Meet someone face-to-face who intimidates you. Contact us; we’re here to help.

“Be proud of your lived experience, and instead of seeing it as a disadvantage,” advised Ramirez, “see it as the gift you’ll provide to the university classroom and to the research you do. You have more to offer than you think.” He also urged them to take an ethnic studies course.

“Be yourself. Educate Berkeley about you,” added Luisa Armijo. “It’s to Berkeley’s credit that you’re here. You enrich the campus. Whatever you dream about, that can become a reality here.”

Ruben Canedo, chair of Berkeley’s Basic Needs Committee, told students that they’re “the next generation of Armijos” and challenged them to “ask what we need to do at Berkeley so that people feel like they belong, feel better supported.”

“Our Coachella Valley needs you back,” stressed Oscar Armijo, who provided closing remarks. “We need your talents. There’s a lot of stuff to be done over there, and you are the future of our valley.”

“Develop the skill of giving,” he added. “There is a lot of need out there, and we all have something to give.”

Figueroa and other guests lingered and networked at Shorb House after the event, savoring time with their extended family at Berkeley and admiring the Armijos’ generosity and heart.

“I love what the Armijos do, and it motivates me to do the same,” he said. “And if we’re united like this, there will be change.”