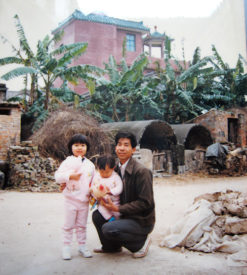

I was born in mainland China, and I was 1 when my family came to the States. My sister was 5. We were the last in our family to come to the States, and are an example of the kind of chain migration Trump rails against. My father passed away just shortly before we arrived.

Henry Wei Leung is a first-year student at Berkeley Law. (UC Berkeley photo by Anne Brice)

Two of my uncles swam across the border to Hong Kong at different times, seeking asylum after the devastation of the Cultural Revolution. They lived and worked there for a decade, then were offered refugee status in the U.S. From what I was told, they were also offered some kind of travel stipend. They agreed to emigrate, but declined the stipend because they had been working and could pay their own way. Over the course of the next couple decades, most of my family migrated to the States. My first uncle, who ended up in Honolulu, took us in to live with him until I was 9, then we moved to Alameda in the Bay Area.

Henry, 1, and his sister, 5, with their father in a village near Zhongshan in Guangdong province, China. Their father died shortly before the family immigrated to the U.S. (Photo courtesy of Henry Wei Leung)

It was very hard for my mom. It’s still very hard for her. She speaks a little English, but it’s broken. She’s very nervous if she has to do anything outside of her normal routine.

While she was working as a waitress, she took night classes to get her AA, in order to get a job with a higher pay. And my sister and I would edit — and sometimes even write — her papers because she didn’t have the time for it. And so, from a really early point, it was clear to me that knowing English and being able to manipulate the written form meant being able to change your material circumstances. That was very real for us.

As a kid, I didn’t think about college at all. I thought I might be a martial arts teacher, or join the military. It wasn’t until I was 15 when my high school English teacher sent me information about a summer writing program hosted by the National Book Foundation in New York. I just applied on a whim. It was there that I discovered poetry.

I discovered people who had committed their lives to poetry, who were making, not a living out of it, but a life out of it. I decided, “Okay, I want to do this. I want to be a poet. I want to immerse myself in writing and language and literature.”

Leung and his mom in Zhongshan. It was her first visit back home after many years to a much-changed city. (Photo courtesy of Henry Wei Leung)

It was radical for me. But it was really important for me, too, because what I saw — and still see — with my mom’s life is that not having access to the imperial language is not having access to power. So, poetry, to me, was an avenue into some form of mastery over your social circumstances. And mastery of your own story.

After high school, I went to Stanford on a full ride scholarship. I didn’t like it there. I wasn’t used to being around so much privilege and entitlement. So, I studied abroad as much as I could. Traveling was eye-opening to me in many ways. Seeing that people around the world have different ideas about what it means to do well or have a good life allowed me to dismantle my own assumptions about success and having a good life.

There’s a theory of language, the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, that says our language dictates our worldview. That what you have words for is exactly the limit of what you can grasp of the world itself. If you don’t have the language for it, there’s no way you can imagine beyond that. I looked at this even on a grammatical level and wondered, “If we were to look at how stories are told in different languages, or even with hybrid languages like in Hong Kong, would we see that stories, structurally, are not so universal after all?”

With a stack of library books, Leung (far left) sits with other protestors in the Admiralty camp in Hong Kong. (Photo courtesy of Henry Wei Leung)

After I got my MFA in Michigan, I went to Hong Kong as a Fulbright scholar in 2014. My plan was to spend most of the year in libraries, but I found my library on the street instead.

There was a protest happening in Hong Kong called the “Umbrella Movement.” It was the most historic protest in Hong Kong history. The mainland Chinese government was constitutionally bound to give universal suffrage to Hong Kong people. And what they finally offered was one person, one vote; but Beijing would preselect the candidates. So, students in Hong Kong went on strike.

It was really about the future of Hong Kong and about autonomy in the face of a second colonialism. It was about a disappearing quasi-nation. So much of what was supposed to be preserved by the Sino-British Joint Resolution has already been lost or fatally infringed. The Hong Kong identity is disappearing because of, for example, an imposition of Mandarin over Cantonese. Schools are now being subsidized if they teach in Mandarin instead of Cantonese. It’s the erasure of a mother tongue. Even food names are starting to change into a Mandarin-equivalent.

Leung leads an Earth Day poetry workshop on the rooftop of Hong Kong University, a few months after the protests. (Photo courtesy of Henry Wei Leung)

During that time, I was writing what became my book of poems, Goddess of Democracy: an occupy lyric. The Goddess of Democracy was a giant papier-mache statue in Tiananmen Square that was raised by students shortly before the massacre. It was one of the first things the tanks destroyed. Replicas of the statue have appeared all around the world, and in Hong Kong it remains an important symbol of mainland resistance.

My time in the Umbrella Movement drove me to transform my skills as a writer and pursue a career in law instead. Now, as a law student at Berkeley, I’m still answering the same question: “What are the fundamental structures in language that determine how we see the world and shape it with our stories?” I think entering the legal profession is another way of framing and structuring narratives, but in a way that intends to change their outcomes.

I definitely never wanted to go to law school — not until recently. My mom had always told me I should, and now that I finally am, she says, “Are you sure you don’t want to be a doctor?”

This is part of a series of thumbnail sketches of people in the UC Berkeley community who exemplify Berkeley, in all its creative, scrappy, world-changing, quirky glory. Are you a Berkeleyan? Know one? Let us know. We’ll add your name to a drawing for an I’m a Berkeleyan T-shirt.