The 1969 strike at UC Berkeley was just the beginning of Oliver Jones’s battles

After helping get the university to budge on adding an ethnic studies program, the activist went on to defend minorities and the environment in a 40-year career as a lawyer

February 5, 2019

Oliver Jones (beige jacket and sunglasses) was at the leading edge of the 1969 Third World Liberation Front strike in Berkeley that led to the founding of the Department of Ethnic Studies. (Photo courtesy of Oliver Jones)

There’s a black-and-white photograph, 50 years old now, that Oliver Jones keeps close at hand.

Taken in 1969 at UC Berkeley at the height of the Third World Liberation Front strike, it shows a large group of TWLF activists, a coalition of ethnic groups pushing for more diversity in the university, marching through Sather Gate. There is purpose in their stride. Almost all of them are looking directly at the photographer, unwilling to back down from the lens or from the moment.

Think of the Jets and the Sharks in West Side Story. That photo defined a generation in much the same way.

At their head is Jones, who would go on to be one of the most significant African American faces of the strike. He would go on to help found the Black Student Union.

While growing up in Oakland, Jones never thought his path would include Berkeley. Five miles away, it was the top-ranked public university in the nation. It might as well have been five light-years away.

He left Fremont High in East Oakland with the intention of enrolling at San Francisco State in 1966. But, “I had no money,” he says, so he instead enrolled at Merritt Junior College. He would wait to see what the future would bring.

He had no way of knowing it was the immediate past that would shape his future.

The Watts riots in Los Angeles in the summer of 1965 had many repercussions, one of which was seeing the University of California, in general, and Chancellor Roger Hynes, in particular, pump energy into what had been, a lackluster history of minority student enrollment.

Berkeley went to high schools, to be sure, in pursuit of African American students, but it also went to Bay Area junior colleges and the armed services.

Jones was a willing listener when a recruiter named Billie Nielsen came calling.

“I transferred in from Merritt College after being there for a semester,” Jones says of his arrival at Berkeley in the fall of 1967. “Billie Nielsen, she was the point person, and she was largely responsible for the group that came in.”

The recruitment changed Jones’s life. It changed the University of California, too.

“You have to put that time into some historical context,” Jones says. “It was the ‘60s, a time of political activism. You had the civil rights movement. You had the threat of the draft. But it was a new time, too. The university had very few African Americans, fewer Hispanics, next to no Native Americans. The only minority that had decent numbers were the Asians. Berkeley was smaller than it is now, about 25,000 students, but the absence of minority students was obvious as soon as you got there.”

“When I got there,” he adds, “it was with a very diverse group of actively recruited minority students. It was a change. And it was the ‘60s. It was a time where there was a general questioning of everything.”

One of the questions that arose concerned the Berkeley curriculum. Another dealt with the makeup of the faculty. The teaching being offered at the time didn’t devote much time to concerns of minorities, and the faculty was heavily white. By 1968, Berkeley students, just like San Francisco State students across the bay, were advocating for a Third World College. When it didn’t come in the first few months of 1969, the student activists went on strike.

The minority groups coalesced into the Third World Liberation Front. But while the Hispanic, Asian and Native American groups came into the union united among themselves, it wasn’t so for African Americans.

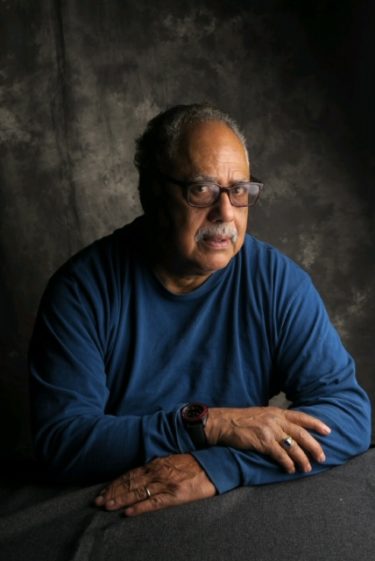

Oliver Jones (Photo courtesy of Oliver Jones)

“You have to realize that African American students were divided,” Jones says. “There was the African-American Students Association. It had a different orientation than the Islamic group that was aligned with the Black Muslims. And then there was my group, which morphed into the BSU (Black Student Union). There were divisions in the community.”

Harvey Dong, now a lecturer in the Department of Ethnic Studies, says Jones was out in front from the beginning.

“Oliver was there for almost all of the marches,” Dong says. “The African American groups were not monolithic at all. Some leaned more toward the Black Panthers, others believed in a separate state, and there were even some Black Muslims. For Oliver, I think he was someone who knew everybody, who knew all the different influences that were part of the black student movement.”

Even with those fractures, the Berkeley strikers held together for 10 weeks. That the strikers held out so long was due, in large part, Jones says, to others who had been recruited — Vietnam-era veterans.

“In the strike, veterans had a disproportionate impact,” Jones says. “They were older and more experienced and less likely to be intimidated. Those were all important lessons to be learned.”

The Third World College they’d advocated for would never happen, but an ethnic studies program and a program for hiring more minority faculty members were both initiated.

“Looking back, the university was a tough nut to crack,” says Jones, who stuck around to get a law degree from Berkeley and went on to champion persons and causes close to his heart and his community. “With the strike, we got our foot in the door. Everybody involved in that strike knew that they could face sanctions and retaliations for what was going on. It didn’t deter us. It was a rebellious time, at the same time as the strike, and people were still fighting the draft and the Vietnam War.”

One of those fighters was Jones. During the ethnic studies strike, he got his 1-A notice from the Selective Service System. He was being drafted. He says it was, “for me, a radicalizing moment.”

And the possibility of being drafted helped make him a lawyer.

“One day I went to Eshleman Hall, the old one,” Jones says. “I met up with a kid there. We talked about the draft, and when I said I’d gotten my letter, he said, `Don’t worry.’”

That chance encounter led to a meeting with Berkeley law professor Richard Buxbaum, the man who would go on to become the first director of the Earl Warren Legal Institute at Berkeley. Buxbaum, currently an emeritus professor at Berkeley, spent much of the late ‘60s guiding unwilling draftees through the conscientious objector legal statutes. Jones says Buxbaum told him, “We’re going to bury you so deep in this statute they’ll never be able to dig you out.”

That proved to be prophetic. Jones was granted conscientious objector status.

“The power of the university and what it could do became clear and had a lasting impact on me,” Jones says. “I went to law school while still a conscientious objector. My first job was with the NAACP’s regional council for the western states. That all led me to being the lawyer I became.”

He would go on to become one of the first lawyers to successfully sue police departments in Richmond, San Francisco and Oakland over their policies. He also successfully represented individual minority officers trying to break onto police force rosters. Along the way, says Jones, “I helped get rid of the department’s height requirements. It was first to help women get on the force, but it turned out to help open the door for Asians and Hispanics, too.”

Jones practiced law for 40 years, later focusing on the environment in suits against Chevron and Safeway over toxic issues. He and his wife, labor leader Katrina Lopez, had five children, “none of whom wanted to go to Cal,” he says.

Jones was one of the featured guests at the Jan. 22 rally on the steps of Sproul Hall on the 50th anniversary of the 1969 strike. He says of his role, “I just happened to be at the right place at the right time.”

“It was a political struggle, and it led to political results,” says Jones. “That’s to be expected. So, you have to look at what happened in context. It took a generation for these departments to be truly embraced by the institutions in the university. And the fight is not over.”