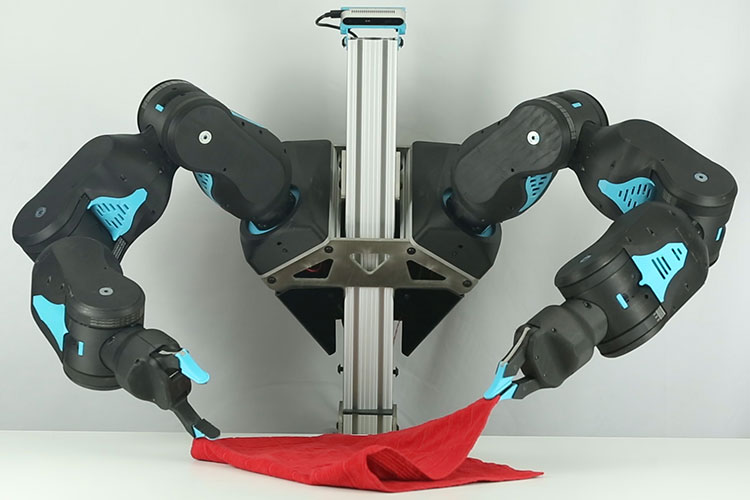

Meet Blue, the low-cost, human-friendly robot designed for AI

Blue’s creators hope the new robot will accelerate the development of robotics for the home

April 9, 2019

Robots may have a knack for super-human strength and precision, but they still struggle with some basic human tasks — like folding laundry or making a cup of coffee.

Enter Blue, a new low-cost, human-friendly robot conceived and built by a team of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley. Blue was designed to use recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and deep reinforcement learning to master intricate human tasks, all while remaining affordable and safe enough that every artificial intelligence researcher — and eventually every home — could have one.

Blue is the brainchild of Pieter Abbeel, professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences at UC Berkeley, postdoctoral research fellow Stephen McKinley and graduate student David Gealy. The team hopes Blue will accelerate the development of robotics for the home.

“AI has done a lot for existing robots, but we wanted to design a robot that is right for AI,” Abbeel said. “Existing robots are too expensive, not safe around humans and similarly not safe around themselves – if they learn through trial and error, they will easily break themselves. We wanted to create a new robot that is right for the AI age rather than for the high-precision, sub-millimeter, factory automation age.”

Over the past 10 years, Abbeel has pioneered deep reinforcement learning algorithms that help robots learn by trial and error or by being guided by a human like a puppet. He developed these algorithms using robots built by outside companies, which market them for tens of thousands of dollars.

Blue’s grippers holding a planetary gear set. (Phillip Downey photo)

Blue’s durable, plastic parts and high-performance motors total less than $5,000 to manufacture and assemble. Its arms, each about the size of the average bodybuilder’s, are sensitive to outside forces — like a hand pushing it away — and has rounded edges and minimal pinch points to avoid catching stray fingers. Blue’s arms can be very stiff, like a human flexing, or very flexible, like a human relaxing, or anything in between.

Currently, the team is building 10 arms in-house to distribute to select early adopters. They are continuing to investigate Blue’s durability and to tackle the formidable challenge of manufacturing the robot on a larger scale, which will happen through the UC Berkeley spinoff Berkeley Open Arms. Sign-ups for expressing interest in priority access start today on that site,

“With a lower-cost robot, every researcher could have their own robot, and that vision is one of the main driving forces behind this project — getting more research done by having more robots in the world,” McKinley said.

From moving statue to lithe as a cat

Robotics has traditionally focused on industrial applications, where robots need strength and precision to carry out repetitive tasks perfectly every time. These robots flourish in highly structured, predictable environments — a far cry from the traditional American home, where you might find children, pets and dirty laundry on the floor.

“We’ve often described these industrial robots as moving statues,” Gealy said. “They are very rigid, meant to go from point A to point B and back to point A perfectly. But if you command them to go a centimeter past a table or a wall, they are going to smash into the wall and lock up, break themselves or break the wall. Nothing good.”

If an AI is going to make mistakes and learn by doing in unstructured environments, these rigid robots just won’t work. To make experimentation safer, Blue was designed to be force-controlled — highly sensitive to outside forces, always modulating the amount of force it exerts at any given time.

“One of the things that’s really cool about the design of this robot is that we can make it force-sensitive, nice and reactive, or we can choose to have it be very strong and very rigid,” Gealy said. “Researchers can adjust how stiff the robot is, and what kind of stiffness — do you want it to feel like molasses? Do you want it to feel like a spring? A combination of those? If we want robots to move toward the home and perform in these increasingly unstructured environments, they are going to need that capability.”

Blue’s creators, Pieter Abbeel, David Gealy and Stephen McKinley. (Phillip Downey photo)

To achieve these capabilities at low cost, the team considered what features Blue needed to complete human-centered tasks, and what it could go without. For example, the researchers gave Blue a wide range of motion — it has joints that can move in the same directions as a human shoulder, elbow and wrist — to enable humans to more easily teach it how to complete tricky maneuvers using virtual reality. But the agile robot arms lack some of the strength and precision of a typical robot.

“What we realized was that you don’t need a robot that exerts a specific force for all time, or a specific accuracy for all time. With a little intelligence, you can relax those requirements and allow the robot to behave more like a human being to achieve those tasks,” McKinley said.

Blue is able to continually hold up 2 kilograms of weight with arms fully extended. But unlike traditional robot designs that are characterized by one consistent “force/current limit,” Blue is designed to be “thermally-limited,” McKinley said. That means that, similar to a human being, it can exert a force well beyond 2 kilograms in a quick burst, until its thermal limits are reached and it needs time to rest or cool down. This is just like how a human can pick up a laundry basket and easily carry it across a room, but might not be able to carry the same laundry basket over a mile without frequent breaks.

“Essentially, we can get more out of a weaker robot.” Gealy said. “And a weaker robot is just safer. The strongest robot is most dangerous. We wanted to design the weakest robot that could still do really useful stuff.”

“Researchers had been developing AI for existing hardware and, about three years ago, we began thinking, ‘Maybe we could do something the other way around. Maybe we could think about what hardware we could build to augment AI and work on those two paths together, at the same time,’” McKinley said. “And I think that is a really dramatic shift from the way a lot of research has taken place.”

RELATED INFORMATION