How a botched train robbery led to the birth of modern American criminology

To help solve the case, authorities called in up-and-coming criminologist Edward Oscar Heinrich, a UC Berkeley lecturer and alumnus whose collection of crime materials is now open at the Bancroft Library

April 30, 2019

On October 11, 1923, three brothers — Hugh, Ray and Roy DeAutremont — boarded a Southern Pacific Railroad train called the Gold Special near the Siskiyou Mountains in Oregon. The trio planned to rob the mail car. But instead of making off with their fortune, they killed four people and blew up the mail car — and the valuables inside. A huge manhunt followed, and authorities called in up-and-coming forensic scientist Edward Oscar Heinrich, a UC Berkeley lecturer and alumnus, to help solve what became known as the Last Great Train Robbery. He didn’t know that the case would put him on the map as a pioneer in modern American criminology.

And now, nearly 100 years later, Heinrich’s collection of crime materials from this case — and thousands of others he worked on throughout his career — are available for research in the Bancroft Library’s archives at UC Berkeley.

Pioneer American criminologist Edward Oscar Heinrich’s crime collection opened at the Bancroft Library in December 2018. (Photo © the Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, cubanc00005983_ae_a)

Read the transcript of Fiat Vox episode #54: “How a botched train robbery led to the birth of modern American criminology:”

A not-so-great train robbery

Anne Brice: On October 11, 1923, three brothers — Hugh, Ray and Roy DeAutremont — boarded a Southern Pacific Railroad train called the Gold Special near the Siskiyou Mountains in Oregon.

[Music: “Sweetly” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The trio planned to rob the mail car — a crime that had seen an uptick in recent years.

After they jumped onto the train as it was emerging from a tunnel, they shot and killed the brakeman, engineer and fireman. Then, they used dynamite to blow their way into the mail car.

But they used too much, and not only did the explosion kill the mail clerk, it also sparked a fire that destroyed the mail car and the valuables inside of it.

The brothers made a run for it — most people think empty-handed — with four dead bodies in their wake.

Crews work at the scene of a train robbery in the Siskyou Mountains in 1923. (Photo from the Edward Oscar Heinrich papers, BANC MSS 68/34 c, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Officials launched a huge, worldwide manhunt. They brought in tons of people to help track down the murderers — officers from surrounding agencies, postal inspectors, the National Guard and hundreds of volunteers. Pilots even flew airplanes over the mountains in search of the criminals — something that was unheard of at the time.

Although other train robberies happened in the U.S. after this, this one became known as the Last Great Train Robbery.

And, officials brought in an up-and-coming criminologist: UC Berkeley lecturer Edward Oscar Heinrich.

Heinrich didn’t know that this case would put him on the map as a pioneer of American criminology — who would go on to earn nicknames like the “American Sherlock Holmes.”

For the first time, files from this case — and thousands of others that Heinrich worked on, along with crime scene evidence and other things from his crime lab — are officially available to use for research in the Bancroft Library’s archives at UC Berkeley.

[Music: “Noe Noe” by Blue Dot Sessions]

There’s no other collection like it in the world.

This is Fiat Vox, a Berkeley News podcast. I’m Anne Brice.

The Heinrich collection at Berkeley

Anne Brice: The collection spans nearly 150 linear feet of crime lab materials — photographs, diaries, notes, newspaper clippings, letters and pieces of evidence — that shed light on some of America’s most notorious criminal cases that happened during Heinrich’s career, from the late 1910s to his death in 1953.

Tor Haugan is a writer at the UC Berkeley Library. He published an article about Heinrich and the collection earlier this month.

He and I spoke with Lara Michels, head of archival processing at the Bancroft Library.

Lara Michels, head of archival processing at the Bancroft Library, took about a year to process the Edward Oscar Heinrich collection. It was donated to the library by Heinrich’s son, Mortimer, in 1969. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Tor Haugan: Lara spent about a year processing the Heinrich collection, which was donated by Heinrich’s son, Mortimer, in 1969. The collection officially opened in December of last year.

Read Tor Haugan’s story about the Heinrich collection on Library News. The article explores three notorious cases Heinrich worked on: the DeAutremont train robbery, a major Hollywood scandal and a pair of killings that weren’t solved until decades after Heinrich’s death.

Fifty years might kind of seem like a long time to not process a collection like this. But, Lara she says, there were good reasons to wait.

First, it was important that plenty of time had passed after these crimes happened.

Lara Michels: Some of the crime scene photos in the collection are very graphic. These are victims of rape and murder. So, there’s a lot of sort of going back and forth about not only how much I can make these available, but also how much I reveal names of people and things like that.

Anne Brice: If the crimes had occurred more recently, an archivist might be compelled to exclude certain items from the collection to protect victims’ identities and their families’ privacy.

In the end, Lara retained almost everything in the collection, save some biological and physical specimens that would be easily lost and hard to prepare and view, like single strands of hair or single fiber samples from carpets.

Lara says she retained almost everything for the collection, including three guns. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Tor Haugan: Another reason is that it took so long to process this collection is that it was a really big undertaking.

There’s only one full-time permanent processing archivist at Bancroft. Lara’s job is actually to oversee archival processing, not necessarily to process collections herself.

But last year, a researcher had asked Lara her about using Heinrich’s materials for a project they were working on, so Lara looked into it.

Anne Brice: And once she did, she was hooked. She says the collection is unlike anything she’s worked on.

Lara Michels: He was a very meticulous person. You see that in the way he kept his records. He was really careful, really documented everything, very systematic.

One of my favorite things in the collection are his work diaries. He kept these meticulous work diaries his whole life, where he writes down everything he’s doing during the day — what he’s doing on any case at one time, all of the appointments. They’re like a treasure trove to really see how he approaches cases.

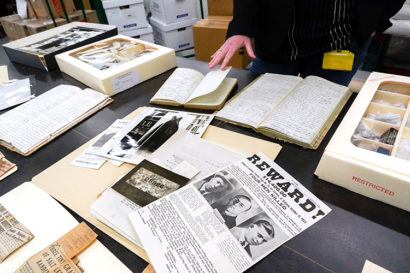

Heinrich saved newspaper clippings from cases he worked on throughout his career. (UC Berkeley Library photo by Jami Smith)

Anne Brice: When archivists work, she says, they’re thinking about the content of the collection, but also about the context for its creation.

Lara Michels: I think my biggest responsibility is to make sure that I communicate to future users not just what’s in the collection, but how it was created, why it was created, what were the purposes around its creation.

Anne Brice: So, unlike a lot of other collections, which might not include much information about certain items, the Heinrich collection is rich with context.

[Natural sound: Lara showing and talking about Heinrich’s collection]

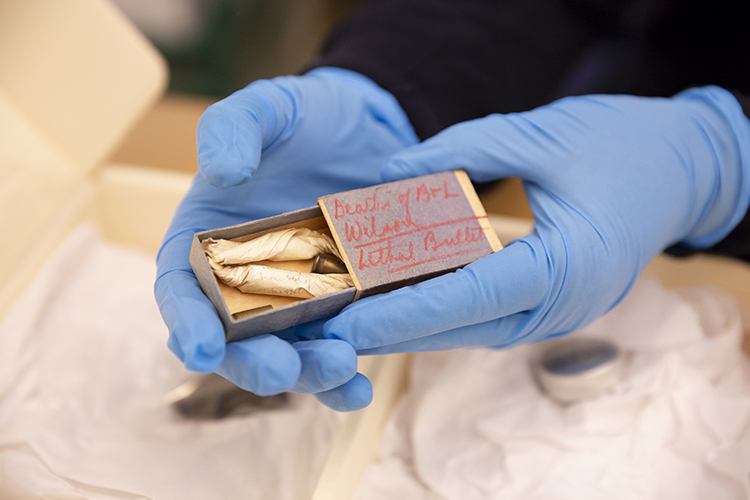

Lara Michels: This is the work that he did. He gathered all the materials from around. These are from a murder in Mariposa County. Two people were murdered. These are the lethal bullets, so these are the actual bullets used to the people. Heinrich stored them in a matchbox, as you can see. He labeled them “lethal bullets.” He tended to wrap all his evidence in paper. And these are test bullets — he did ballistics, so he had test bullets and lethal bullets and he could compare them.

Heinrich wrapped bullets in little bits of paper and stored them in matchboxes. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Tor Haugan: Because Heinrich began working as a forensic scientist in 1919, there weren’t really any regulations in place for what he could and couldn’t do. So he would just go onto a crime scene and collect evidence and take it back to his lab.

Anne Brice: Or he might ask the police to examine evidence — like a gun — and never return it.

Tor Haugan: So there are three guns in the collection. When Lara found them, she actually had to call UCPD to come disable them. That was a first for her.

Anne Brice: While Lara was going through all the materials, she says she felt like she really got to know Heinrich.

Lara Michels: There is, when you process, a sort of emotional connection or a responsibility you start to feel for the creator of the papers and for the other people who are documented in the papers and for the victims of the crimes. So, being an archivist, there is sort of an emotional part to it. We don’t talk about that a lot, but it’s there.

[Music: “An Introduction to Beetles” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Anne Brice: She learned about Heinrich’s life — his father’s suicide, his anxieties about finances, how he talked his way into attending the University of California.

And she learned about how he taught himself forensic science — an emerging field that he would use as an expert witness to sway juries in prominent cases.

Court testimony by Heinrich. The pioneering forensic scientist was a well-known expert witness — one who could sway juries with science. (UC Berkeley Library photo by Jami Smith)

Lara Michels: He knew how to present evidence, and he was in demand as an expert witness. Frankly, he knew how to sell himself as an expert witness, too. When I think of Heinrich, I think of him as an expert witness and a scientist who could play that role and give that sort scientific legitimacy to a case.

I think that’s why people sought him out — because they knew that he could help them win their cases. The public was sort of fascinated by science in the courtroom, and he was part of that.

How Heinrich used science to name the murder suspects

Anne Brice: While investigating the train robbery-gone-way-wrong, authorities had come across a cabin in Siskiyou County that the criminals had stayed in while on the run.

So Heinrich took the train from Berkeley, where he was running a crime lab out of his home, to the cabin in Oregon, where he took photos and collected evidence. Then he brought it all back to analyze in his lab.

After the DeAutremont Brothers were named as suspects in the botched train robbery, more than 2 million wanted posters were printed in English, French, Portuguese, German and Dutch. (UC Berkeley Library photo by Jami Smith)

Authorities had found a pair of overalls in the cabin that had an oil spot on them, so they assumed the overalls belonged to a local mechanic.

But at his lab, Heinrich found that the spot was actually pitch from a tree and determined that authorities should really be looking for a lumberjack — one who lived and worked in the Pacific Northwest and was white, in his early 20s, about 5’10,” with light brown hair.

Lara Michels: He dug through the pockets of the overalls to find little bits of lint and pine trees, and then he put it under his microscope. I mean, that’s very common now, but back then, it was less common. He was one of the first to really do that.

Anne Brice: In the 1958 book, the Wizard of Berkeley, author Eugene Block writes that Heinrich also figured out the suspect was left-handed after he found wood chips in the right pocket. (A left-handed lumberjack’s right side would be closest to the tree as they chopped, so the right pocket would catch flying wood chips.)

And from other clues and evidence that Heinrich collected — like purchase records and a signature — the DeAutremont brothers became suspects.

Heinrich figured all of this out using forensic science, which he taught himself. He’d learned at a young age that people depended on him and that if he wanted to succeed, he’d have to figure out any way he could to make it happen.

[Music: “Base Camp” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Who was Edward Oscar Heinrich?

Heinrich examines a Palo Alto scene of the 1933 murder of Allene Lamson. Allene’s husband, David, was tried for the murder in a trial that became a tabloid sensation. (Photo from the Edward Oscar Heinrich papers, BANC MSS 68/34 c, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Anne Brice: When Heinrich was a teenager, his father killed himself. And it became Heinrich’s job to support his family. So he trained himself to become a pharmacist.

At 18, he passed the boards and began working as a pharmacist in Tacoma, Washington, where he grew up.

But he felt like he needed more training, so he came to the University of California — which later became UC Berkeley — to learn chemistry. He didn’t have a high school diploma and was told he couldn’t attend.

So he petitioned for reconsideration, and in 1904, he was let in as a special status student.

In 1908, he graduated with a degree in chemistry. And the same year, he married an education student he met at Berkeley named Marion, with whom he would have two sons.

Then, after stints as a chemist in Tacoma, Washingon, a police chief in the city of Alameda and a city manager in Boulder, Colorado, Heinrich was pulled back to Berkeley in 1916 by the death of a famous handwriting analyst and expert witness, Theodore Kitka. Heinrich came back to take over Kitka’s practice.

Then, in 1919, Heinrich started his own crime lab in the basement of his Berkeley home on Oxford Street.

In the summer, Heinrich would teach criminology at UC Berkeley — he taught the first criminology course offered anywhere in the country.

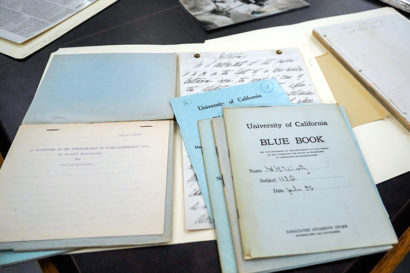

Lara Michels: We have these great essays. He had his students write about the very first criminology course offered anywhere in the country. He taught it. And he had them write these blue book essays evaluating the course.

Heinrich, who taught the first criminology course in the U.S. at UC Berkeley, asked his students to review his class as their final exam. (UC Berkeley Library photo by Jami Smith)

So you get these really interesting perspectives from these students who are being exposed to something that’s totally new, and they’re really fascinated. And that Heinrich had his students do that as their final assignment to evaluate the course was a really interesting choice on his part. I think he was actually a really good teacher, as far as I can tell.

Anne Brice: In the collection, you can almost see step by step how Heinrich taught himself forensic science.

Lara Michels: He had a vast library, which we have most of at the Bancroft Library. We’ve catalogued all of his library. So you’ll find all kinds of interesting books about wax substances. He was self-taught in ballistics, all of his handwriting analysis skills were self-taught, ink analysis, typewriting analysis, blood spatter analysis, all of that. He was really a jack-of-all-trades, I think.

So he taught himself almost everything he knew.

Anne Brice: Lara says the bread and butter of his work was analyzing handwriting and typewriting. In any given month, he might’ve been working on 30 to 40 cases, and most of them were for fraud or forgery or other crimes like that.

Lara Michels: He had his own way of doing handwriting analysis. What I found throughout the collection were these little, teeny cut-out letters. He would photograph letters, enlarge them, cut them out. They’re just all over the place in this collection.

Lara says the bread and butter of Heinrich’s work was handwriting and typewriting analysis. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Anne Brice: When the U.S. entered World War I, in 1916, Heinrich worked for the U.S. Army’s Military Intelligence Corps, which had intercepted documents about a conspiracy by German-supported Hindu revolutionaries who planned to incite an uprising in India, which would have diverted British forces.

To decode the documents, Heinrich worked with tutors to learn three East Indian dialects. Then, he analyzed the handwriting, typewriting and ink. And he was able to prove who wrote dozens of the documents.

There was another famous case in the 1920s that involved Heinrich. A priest was murdered in the South Bay, and Heinrich examined threatening, anonymous notes written to the priest. He figured out that they were written by a baker by the way the letters were formed — just like writing on a cake.

And after a four-year investigation, Heinrich’s work on the DeAutremont brothers’ case would finally pay off.

Case closed, collection opened

[Music: “Maldoc” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Anne Brice: In 1927, the DeAutremont brothers were finally caught.

Hugh — the youngest — had joined the U.S. Army and was stationed in the Philippines. The other two — twins Roy and Ray — were arrested in Ohio by the FBI.

In 1928, they were convicted and sentenced to life in prison in Oregon.

Hugh was paroled in 1959 and died from cancer a few months later. Roy, who had schizophrenia, was given a lobotomy in prison and died in a nursing home a few months after he was paroled in 1983. Ray, paroled in 1961, spent many years working as a part-time janitor at the University of Oregon in Eugene. He died in 1984.

As for Heinrich, he worked as a forensic scientist until he died in 1953 at age 72.

Lara says that Heinrich will stick with her.

Lara Michels: My sense of his personality will linger with me, more than the cases. That seems strange, but I feel like I got to know Heinrich and how he approached his life and his work.

Lara says Heinrich — who he was and how he worked — will stay with her. (UC Berkeley Library photo by Jami Smith)

Archivists sometimes like to think of themselves as super objective, but that’s sort of nonsense, in a way. You bring your own skills and your own sensibilities to the work that you do. He will linger. I will have a sense of him for a long time.

Anne Brice: Lara says mostly she’s happy that the Heinrich collection is finally open. She’s curious to know how researchers and anyone else interested in the collection will use all of the materials. There haven’t been many requests yet, but she thinks once the news gets out that the collection is open, there will be more interest.

As with most archival collections at the Bancroft Library, the Heinrich collection is stored in an off-site facility. Anyone interested in viewing the collection can create a free account through Aeon — that’s Bancroft’s Special Collections Request System — make a request online, then view the materials in the Bancroft Library’s reading room.

You can find more information on the Bancroft Library’s website at library.berkeley.edu.

For Berkeley News, I’m Anne Brice.

You can read Tor Haugan’s story about the Heinrich collection on Library News. It was also published in Fiat Lux, the library’s quarterly magazine. The article explores three notorious cases Heinrich worked on: the DeAutremont train robbery, a major Hollywood scandal and a pair of killings that weren’t solved until decades after Heinrich’s death.

Listen to other episodes of Fiat Vox: