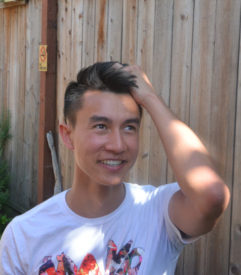

Top graduating senior an aspiring Elon Musk — minus the tweeting

Impish, iconoclastic bioengineering and materials science major is the winner of the 2019 University Medal

May 10, 2019

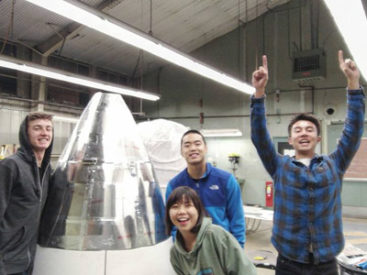

Tyler Chen hadn’t even started his freshman year at UC Berkeley when he began scouting for students on campus with engineering talent. He was looking to assemble a team to bring to life Elon Musk’s futuristic vision of a levitating train shooting through a vacuum tube at 750-plus mph.

Two years later, Chen’s Berkeley Hyperloop team advanced — after beating out more than 1,000 other contenders — to the 2017 finals of SpaceX’s hyperloop pod competition. With a glitch in the control system, though, the pod barely survived the U-Haul truck ride to the company’s headquarters in Hawthorne, California, let alone the test track.

“We tried to rebuild it at the last minute, but we couldn’t even test it on the track,” recalls Chen, 21, a native of Carlsbad, California. “The whole thing was really, really painful.”

A relentless optimist, he got back on track superfast, and it paid off.

Chen, a joint major in materials science and bioengineering, is this year’s winner of the University Medal, UC Berkeley’s highest honor for a graduating senior. In addition to receiving $2,500, he will give a speech to thousands of his peers at a campus-wide commencement ceremony at California Memorial Stadium on Saturday, May 18.

His resumé boasts a succession of impressive scientific and technological breakthroughs, plus a near-perfect GPA of 3.96. And don’t be fooled by this lean ectomorph: Chen has a third-degree black belt in taekwondo and trains in “tricking,” a high-octane combo of martial arts and parkour.

This fall, he starts Ph.D. studies in bioengineering as a Knight-Hennessy Scholar at Stanford University. His goal is to develop neural devices that enable people with paralysis, speech impairment and other neurodegenerative diseases and muscle disorders to communicate “using their minds alone.”

‘The complete package’

“Tyler is one of those rare students who exhibits the complete package of exceptional intellectual abilities, superior interpersonal skills, leadership, resilience and, at the same time, a humility that makes him a role model to his peers,” wrote Marvin Lopez, director of student programs in Berkeley’s College of Engineering, in his letter recommending Chen for the University Medal.

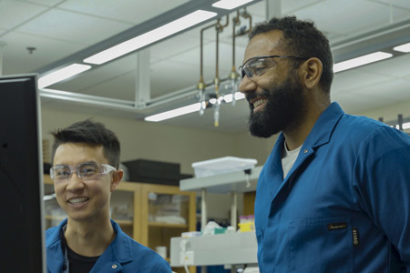

Tyler Chen with Aaron Streets, assistant professor of bioengineering. (UC Berkeley photo by Stephen McNally)

Chen was running microfluidic experiments in a lab in Stanley Hall on a recent Saturday when bioengineering professor Gerard Marriott, chair of the committee that selects the University Medalist, called.

With poor cell reception in the lab, Chen ducked into the hallway so he could make out what Marriott was telling him. The words all ran together, and then he heard, ‘You got it!’”

“I was super-excited. Then I ran back to the lab to check on my experiment,” says Chen. His unassuming demeanor can be quite disarming.

Meet the runners-up

Four other graduates were finalists for the medal.

In addition to co-founding and mentoring the Berkeley Hyperloop team, Chen has spent untold nights and weekends in the Streets Lab in Stanley Hall, designing microfluidic devices to manipulate individual cells for RNA sequencing.

“Tyler has demonstrated a level of gene detection sensitivity that I believe is the highest demonstrated to date. If validated, this result will have a significant impact in the field of single-cell RNA sequencing,” wrote Aaron Streets, an assistant professor of bioengineering and principal investigator at the Streets Lab, in a letter recommending Chen for the medal.

Among other achievements, Chen helped develop carbon nanotube-based biosensors to track the health of astronauts. And, during a two-day campus “makeathon,” he spearheaded a successful effort to build gripping devices for a quadriplegic member of Chen’s team.

A charmed upbringing

He credits the “superstar teams” he’s worked with for his technological and scientific victories. As for his inquisitiveness, iconoclasm and can-do attitude, those characteristics, he says, are rooted in his warm, goofy and intellectually curious family.

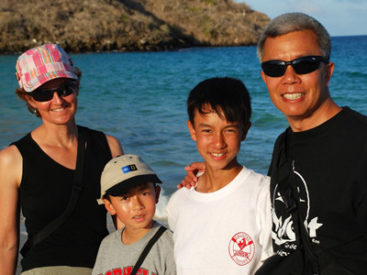

A young Tyler Chen (third from left) with dad, Eugene, brother, Eric, and mom, Katie. (Photos courtesy of Tyler Chen)

His father, Eugene Chen, is a mechanical engineer and the son of Chinese immigrants. His mother, Katie Chen, is a biologist from the Bay Area. They met at UCLA where his younger brother, Eric, is now a freshman in computer science.

Chen recalls an idyllic childhood in an upper-middle-class suburban enclave, a time of youthful pranks, taekwondo (everyone in the family is a black belt) and trips to China, India, Europe, Botswana and the Galapagos Islands.

“From my mom, I get curiosity and joy about the little things in life,” he says. “From my dad, I get that entrepreneurial spirit. He’s always coming up with new ideas and ways to solve problems. My brother is my best friend.”

His school robotics team brought out the impish competitiveness in him.

“I enjoyed coming up with strategies for how to mess with the other team, like using our overdesigned robot to knock over the other team’s robot,” Chen says with a laugh.

In his senior year in high school, he devised a plan to become a tech entrepreneur. It involved sampling as many STEM disciplines as possible to see which would provide the best tools to bring him the most success.

Suffice it to say, when he got to UC Berkeley in 2015, he was like a kid in a candy store. He sampled linear algebra, organic chemistry, physics, bioengineering, mechanical engineering, computer science, applied data science and cell and molecular neurobiology, garnering all As, give or take a plus or minus.

“In the end, I learned that no one discipline or tool is more important than the others, so I have been lucky to touch on each one,” he says.

A lesson in diversity

Looking back on his time at UC Berkeley, Chen says one of his favorite classes was Serena Chen’s social psychology class.

“I learned about how unconscious bias is part of the brain’s shortcut system, and that you can’t assume things about people based on the way they look, because we all come from different backgrounds and see things in different ways,” he says.

And that shaped his thinking at a two-day campus makeathon in March 2017 for people with disabilities.

On Chen’s team was Bonnie Lewkowicz, a quadriplegic and Bay Area advocate for greater disabled access to outdoor recreation. Instead of hearing about Lewkowicz’s overwhelming challenges, team members learned about the small things that make her daily life difficult, like plugging and unplugging electrical cords from outlets and picking up things from the floor.

Team members used a 3D printer to create parts for mechanical devices that would give Lewkowicz gripping strength, including a manual gripper that attaches to her arm and has claws that open upon contact with an object and grasp it. She uses it to this day.

“That’s the whole point of having a diverse team,” Chen says. “If a team is made up of clones of one person, it will only solve problems relevant to that person.”

Tech for humanity’s sake

As for personal highs and lows, Chen experienced the gamut on his Berkeley Hyperloop quest to create a prototype of a levitating vehicle that travels close to the speed of sound, as outlined in Musk’s 2013 white paper.

The highs came when his team’s pod design made the first cut in 2016, and the SpaceX engineers liked it enough to send the team to the finals to compete with 27 other student teams from around the world.

Also exhilarating was the team’s ability to raise $80,000 for industrial materials and other expenses from such big-name companies as Autodesk, General Motors and National Instruments.

But building the pod at Berkeley’s Richmond Field Station presented challenges. On the eve of the competition finals, Chen and his teammates detected a failure in their control system, which they tried like crazy to fix all the way to the competition arena.

“We ended up not winning,” Chen laments. “But afterward, we sat down and hashed out what we did wrong and what we could do better, and the team is still going.”

Musk might do well to hire Chen — though Chen has a lot more on his mind these days than the Hyperloop.

“I really admire Musk’s goal to slow down global warming and ensure the long-term existence of humans. But it seems like his companies are connected to people in the abstract,” he says. “Our generation is more about technology with interpersonal connections.”

Asked about the origin story he would tell techie youngsters who want to follow in his footsteps, Chen pauses for a few beats.

“Once upon a time, there was a boy called Tyler Chen, who wanted to be an inventor. He tried and failed at inventing a lot of things, and learned a lot.

“He helped people be optimistic about the future and understand one another, maybe through technology because, well, that’s what I know best,” he says, cracking an impish smile.