Their workshop’s no palace, but they hold the keys to the kingdom

UC Berkeley’s eight locksmiths guard the master keys to hundreds of buildings on and around the campus

May 30, 2019

Jeff Bovie has handled all manner of calls for help in his 14 years as a locksmith at UC Berkeley. But a recent one threw him for a loop. Suspected intruders had been spotted, via a webcam, heading for the campus’s beloved peregrine falcon family that, since 2017, has made its home atop the iconic 307-foot-tall Sather Tower.

Armed with their tool boxes, Bovie and fellow locksmith Tim Howell sped across campus, ascended the Campanile and installed a lock on a door to a narrow spiral staircase that leads to the fluffy raptors’ nesting area.

Bovie was quite content to stay at the bottom of the stairs, a safe distance from mother falcon Annie, a fierce protector of chicks Carson and Cade.

“You don’t want to be up there when the falcons are there, especially the mother,” says Bovie, a Berkeley native and the campus’s lead locksmith. “Plus, that staircase is very narrow and claustrophobic. It reminds me of the steps at the top of Notre Dame cathedral.”

UC Berkeley’s eight locksmiths guard the master keys to hundreds of buildings on and around the campus, applying expertise, tools of the trade and good humor to assist campus members — including the feathered variety — in a bind.

With literally thousands of secured facilities spanning their coverage area — including structures built in the late 1800s, when the university was young — they fix and even create from scratch hardware ranging from ultra-modern to fascinatingly antiquated.

Steps leading to nesting area atop the Campanile (Photo by Matt Benca)

Their jobs have taken them from the hilly heights of the Lawrence Hall of Science and the UC Botanical Garden down into the vast network of underground steam tunnels built on campus in the early 1900s to provide buildings with heat .

They’ve replaced door knobs mauled by hyenas when Berkeley kept a colony of the bone-crushing predators for research purposes. They’ve climbed up balconies and through windows to free people inadvertently trapped in their offices or restrooms and saved highly sensitive research materials that would have been ruined had they arrived too late.

“We help people in trouble. We protect research, and we get to see every nook and cranny of the university,” says Bovie. “It’s a great job.”

The Facilities Services Lock Shop is headquartered in an underground parking garage near the campus’s West Gate. It used to be in warren-like Dwinelle Hall, which has a layout that’s confusing to new team members.

Calls typically come to the locksmiths through the UC Police Department and a Berkeley Facilities Services dispatcher. They usually involve such predicaments as lost keys, malfunctioning keycards — especially in labs with powerful magnetic materials — and campus upgrades needed for Americans with Disabilities Act compliance.

For the most part, the team has the run of the campus. But sometimes, it needs escorts to enter highly sensitive facilities, such as the basement of Kroeber Hall, where Hearst Museum of Anthropology artifacts are stored, and at the Bancroft Library’s Mark Twain Papers and Project.

In addition to having access to the hidden corners of campus and its environs, the locksmiths get to see, and occasionally even meet, some of its academic celebrities.

“We got to see the ‘Big Bang’ professor,” says locksmith Matt Benca, referring to Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist George Smoot. The group fondly refers to Benca as their “resident intellectual.”

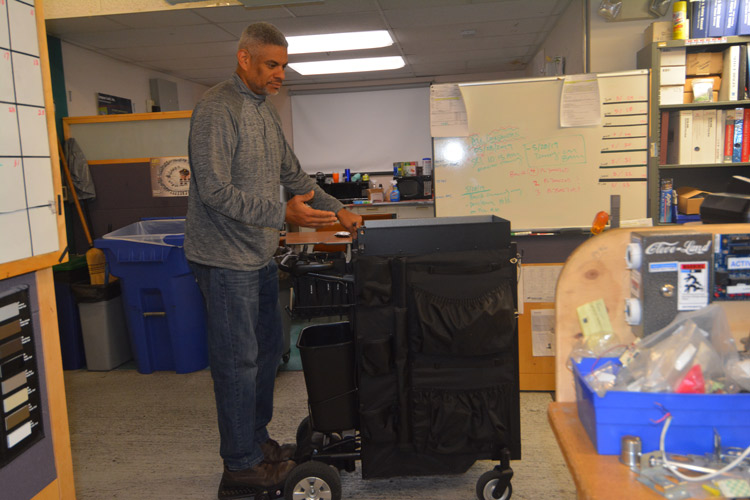

At 6 feet, 2-inches tall, John Camello, a newer team member, is a tad tall for the motorized cart the group uses to get around campus. Still, he gets a kick out of riding past historic spots like Senior Hall, a 1906 rustic log cabin designed by university supervising architect John Galen Howard and used by male students in the early 1900s for secret meetings.

And, even after 14 years, Bovie still gets excited discovering tucked-away places — and people — on campus.

On a recent call for service, he met Candace Falk, a former Guggenheim fellow who is heading up an archival project on Emma Goldman, an anarchist, feminist and prolific writer in the first half of the 1900s who was considered radical by the standards of her time.

“Candace is in this little off-site brick building south of campus where she archives the Emma Goldman Papers and teaches about her,” he says. “She’s really cool.”

It’s encounters like these that make the job a daily adventure, he says.

“We have the keys to the kingdom,” quips Bovie, jangling a master set that includes every imaginable shape, size and vintage.