For Martha Olney, a teaching professor of economics at UC Berkeley, coming out didn’t happen all at once. As a graduate student in 1980, she met her wife, Esther Hargis. A few of their friends knew they were together, but “it wasn’t something you told people.” Esther was a Baptist pastor, so she needed to be careful at the time to protect her career. It wasn’t until the couple decided to adopt their son, Jimmy, nearly two decades later, that they decided they had to live their lives fully out.

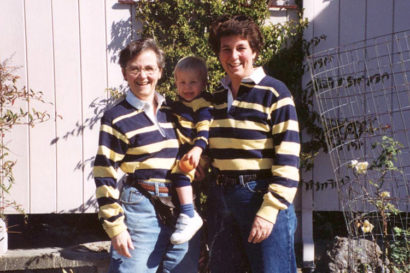

Esther Hargis (left) and Martha Olney in the summer of 1984, soon after they officially became a couple. They met in 1980 when Olney was graduate student at UC Berkeley. “In retrospect, we dated for about three and a half years without actually realizing that’s what we were doing, and then became a couple,” says Martha. (Photo courtesy of Martha Olney)

Following is a written version of Fiat Vox episode #56: “The ministry of being out:”

“So, my wife’s a minister. In the 1980s, being a lesbian Baptist pastor … we knew them all. We knew all of them.”

[Music: “A Rush of Clear Water” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Martha Olney is a teaching professor of economics at UC Berkeley. She met her wife, Esther Hargis, in 1980 as a graduate student at Berkeley.

Martha Olney is a teaching professor of economics at UC Berkeley. (UC Berkeley photo)

“For her career, she needed to be really careful,” says Martha. “And I think she needed to be more careful initially than I needed to be. And that was fine because she’s, frankly, the best preacher I’d ever heard in my life. Still true. And I very much supported her ministry. So, you know, it was a choice that we made. There were some of my friends here in graduate school who knew we were a couple, but it was not something that you told people.”

After Martha got her Ph.D., she took a job as an assistant professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Esther soon joined her and got a job as a chaplain at UMass. They came out to a few people, but they were still really cautious about who knew they were together.

“What does it look like to be partially out, but not totally out? What does that mean? What’s the difference?” I ask.

“It means you’re constantly aware of who is around and thinking about the context and the setting. And always being aware of what you’re saying,” she says. “It takes a lot of work.”

Then, on April 25, 1993, there was the March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation. It was an experience that would change their outlook on what it meant to be gay in the United States.

The March on Washington

Martha and Esther had moved to the Bay Area by this time, and Martha had been splitting her time between UMass and Berkeley, teaching one semester at one campus, then one semester at the other. They two met up in Washington.

[Natural sound: People cheering and marching to music in the March on Washington. Video by John Schuster via YouTube.]

Esther (left), Martha and their friend, Scotty Conover, at the March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation on April 25, 1993. (Photo courtesy of Martha Olney)

“There you were in Washington, D.C. with at least a million, if not more, other gay folk. It was just a mind-blowing experience. So, you know, the experience started in Dulles Airport, where you get off the plane, and you look around, and it’s like, ‘Oh my God, I’ve never seen this many gay people together in one place in my life.’ And then you take the Metro into downtown D.C. and it’s like, ‘Oh my God, I’ve never seen this many gay people together in one place in my life.’ It was just the most amazing experience.”

[Speech from the march: “It’s time to stand up and look America directly in the eye and say, ‘I am not a second-class citizen. I demand immediate equality now in all aspects of life.'” Video by John Schuster via YouTube.]

Even people who they assumed would be opposed to the march were actually there to celebrate.

“We had lunch in the American History Museum, and the Daughters of the American Revolution were having their conference in D.C. at the same time.”

The Daughters of the American Revolution, or the DAR, is a conservative organization for women who are directly descended from someone involved in the American Revolution.

People celebrate at the 1993 March on Washington. (Photo by Elvert Barnes via Wikimedia)

“And so, we were in the cafeteria line, and we were coming up on the desserts, and there were these two women from Texas in line behind us. And one of the women says, ‘Honey, would you like a piece of pie?’

“‘Oh, sure, sweetheart, that’d be great.’

“And it’s like, ‘Oh, are you here for the march?’

“‘Yes, we are.’ And it was like, ‘Oh, my God. Even the people that you look at and you think they’re there for the really conservative convention are there for the march.’

[Speech from the march: “We are brave enough to live in the light. We are brave enough to step out of the closet. We are brave enough to recognize that we love each other, that we have a right to love each other, that we have a duty to love each other. And someday, we will all be free. And someday, we shall live in the light. Thank you.” Video by John Schuster via YouTube.]

“I think that march had a huge effect because I think that that it was impossible for everybody who was at that march to turn around and go back home and go back in the closet.”

But it wasn’t until a big life decision that Martha and Esther felt they had no choice but to live a fully out life.

[Music: “Arizona Moon” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Coming out in Berkeley

After the march, Martha says she was less focused on herself and more focused on the ministry of being out — what it meant to be religious and part of the LGBTQI+ community.

“There’s such a dominant message in so many of the churches that kids are growing up in of, ‘Homosexuality is bad, evil,’ et cetera, sin and so on — all that language. And it just really schmucks up people’s heads, you know? And so, to be part of a ministry where the message was, ‘God made you, God loves you, God don’t make junk.’ That just became really important to me, to all of us.”

During the process of adopting their son, Jimmy, Martha and Esther decided it was time to live completely out. (Photo courtesy of Martha Olney)

By 1996, Martha was teaching economics at UC Berkeley full-time. And Esther had become the pastor of the First Baptist Church of Berkeley. Three years later, they adopted their son, Jimmy.

It was during the adoption process that Esther decided she needed to officially come out to the congregation.

“We both felt really strongly that we had to be out because there was no way to raise a child and say, ‘Oh, honey, when you go to kindergarten, you can’t call us both ‘Mom.’ You can’t do that to a 4- and 5-year-old. And so, deciding to become parents meant deciding we were going to be completely out in our lives, because it just couldn’t be any other way as moms.”

As a professor, Martha made a point to mention during class that she had a woman partner.

“At the time, I would say, ‘my partner, she.’ So, you know, in some context, there was something where I made sure I said, ‘my partner’ and then, I used the pronoun ‘she.’ And now I say, ‘my wife.’”

Martha received a GSI mentoring award in 2015. She says she makes a point to come out to her classes each semester. (Photo courtesy of Martha Olney)

Every time she’d come out to her classes, there’d be students who visited her office afterwards, where they would come out to her and talk about their experiences. Some would say they didn’t know how to tell their parents they were gay.

“It clearly made a difference. It was very scary the first few times I did it because I was afraid there would be hecklers. There have never been hecklers. So, there was a time when it was really important. I don’t know that it’s still as important as it was. Probably. I think being 18 or 19 years old and being queer, depending on where you grow up, still takes some bravery.”

[Music: “A Path Unwinding” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Martha’s also on the Lavender Cal out list. It’s a list of faculty and staff who identify as part of the LGBTQI+ community. It got started in the 1990s — first in print, then online — as a way for students to know who was queer on campus.

Martha says she learns a lot about what it’s like to live as a young gay person from her 21-year-old son, Jimmy, now a junior at Vassar College.

The freedom and risk of being gay today

“All the opportunities you used to be excluded from when you realized you were gay, that’s not true anymore. You know 20, 30 years ago, ‘Oh, I’m gay. I can’t get married.’”

Now, Martha says, same-sex couples can get married wherever they want and can have kids together in different ways, whether it’s through adoption, insemination or surrogacy. There’s a certain freedom that exists today that she didn’t have for much of her adult life.

From left: Jimmy, Martha and Esther. A junior at Vassar, Jimmy has written about the freedom and risk that comes with being gay today. (Photo courtesy of Martha Olney)

Her son, Jimmy, has written several pieces about both the power of just being out and being yourself, but also the risk that it brings with it.

She remembers how Jimmy would walk hand-in-hand with his first boyfriend as a sophomore in high school.

“There was an older gay man who walked up to them in some store, where they were walking along holding hands. And the guy said to them how proud it made him that these two kids could be holding hands and how he’d never had that opportunity. And he just wanted to say something to them about what a wonderful change there is in the world.

“So, I was like, ‘OK. But I’m still your mother and I still want you to be careful.’”

There have also been times where Jimmy’s been out with a boyfriend and has become aware of someone following them. And he won’t take the BART anymore after someone sat behind him and whispered death threats in his ear.

“There’s this freedom, where you can be out with your boyfriend holding hands, and risk. I think no victories are ever won on a permanent basis. We see that right now with abortion rights. I think that’s true with marriage rights. So, I think we always have to remain vigilant.”

[Music: “Alustrat” by Blue Dot Sessions]

It wasn’t until after same-sex marriage became legal in the U.S. in 2015 that Martha and Esther felt comfortable holding hands in public.

“When you’re a new couple, you figure out whose hand goes in front and whose goes behind and how do you put the fingers together. We finally sort of have it down, but we’ve been together 35 years and we’re just sort of figuring out when we hold hands, how do we do it?”

Martha and Esther in Norway in 2018. “We’ve been together 35 years and we’re just sort of figuring out when we hold hands, how do we do it?” says Martha. (Photo by Martha Olney)