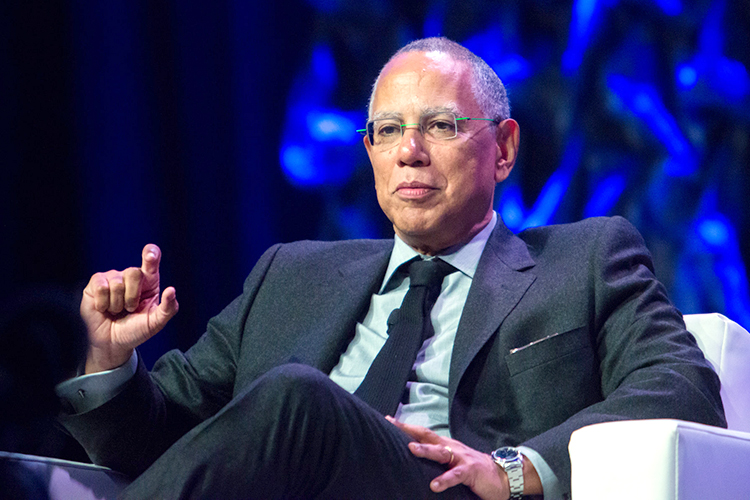

Berkeley Talks transcript: New York Times editor Dean Baquet on the future of fact-based journalism

June 13, 2019

Ed Wasserman: Welcome to On Mic. Conversations from North Gate Hall, home of the University of California Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism. I’m Ed Wasserman, dean of Berkeley Journalism. As one of the nation’s top journalism programs. We regularly invite the world’s best reporters, writers, and documentarians to talk about the stories behind their stories. This week we welcome Dean Baquet editorial chief of the New York Times. Dean Baquet is a punitive prize winning journalist and one of the nation’s most respected and influential editors. In today’s episode, I sit down with Dean to discuss the New York Times’ coverage of Donald Trump during and since the 2016 election, and the future of fact-based journalism.

Dean Baquet: I think if we get so caught up in Donald Trump, one, because not enough stories were written about X, tons of stories were written about X. I think Donald Trump won because there was something going on in the country that we didn’t understand, and still probably sort of don’t quite understand. It’s On Mic with me, Edward Wasserman, in conversation with Dean Baquet.

Ed Wasserman: So let me start with, just as all news nowadays starts, with Donald J. Trump. He presents so many challenges to customary journalistic practice. It’s hard to know where to begin. But, let me just cut through it and asked you kind of a seminal question, which is, if you had it to do over again, would you have covered the 2016 election differently? `

Dean Baquet: Sure. I’m not sure we would’ve covered Trump himself differently because we, I mean, we did a lot of stories about Trump and women he made uncomfortable. We did a lot of examinations of his finances. What I would have done differently, I don’t think the New York Times, actually, I think most news organizations did not have a handle on how much turmoil there was in the country, how much the country was sort of disaffected by the people who, who were running for president. The evidence of that, by the way, it was not just Trump. The evidence was that essentially an elderly democratic socialist gave Hillary Clinton, the established candidate, a run for her money.

That said, pretty clearly the country was in turmoil and was desperate to shake things up and I don’t think we quite saw that. I mean, newspapers and journalists play by a rule book unfortunately, but we, it’s not that we play by rule book because we want to, you just, if you do the same thing for 200 years a rule book develops. And I think this election sort of threw that rule book off. I don’t think we had a handle on just how much of a hanging over there was from the financial crisis, how much anger there was in the country. If you look at our coverage of Trump, it was pretty rugged, but I don’t think our coverage of the turmoil in the country was as strong.

Ed Wasserman: So in light of that turmoil, had you given it enough weight it wouldn’t have affected the way you looked at Trump, the amount of attention you gave to him?

Dean Baquet: I think we would’ve … If we had done … You know, hindsight, the cliche, I think if we had to do it over again, sure, I guess it would’ve changed your coverage of Trump because we would have been covering more of the reaction to Trump than Trump himself. Does that make sense? I think we would have understood better that the country just was not behaving the way it usually behaves in elections. Bernie Sanders was the first signal of that and Donald Trump was the dramatic final powerful symbol of that, and I don’t think we had a handle on that.

Ed Wasserman: Did you have raised reflect on propriety of the coverage of other media of Trump? In particular, I’m thinking of something that Frank Rooney, [crosstalk 00:03:51] paper, other people have written it. I’ve written it. The notion that they gave him an outsized amount of exposure in the belief that his clownishness and as utter unsuitability to be president would speak for itself, and instead that exposure conferred stature on him, he became the central pivotal figure in the campaign.

Dean Baquet: I think because nobody thought he could win. And if you find anybody who says they thought he could win, don’t believe them. He was like, I don’t want to say comic relief. He was doing too well for that. But I think he was a great show and I think television found that show alluring. We did too. But, to be honest, I think television did more cause he was a better television show. But I think it’s a mistake and it’s a big mistake to think that Donald Trump won because there was press coverage. I think that’s missing something large that happened in the country in 2016. I’m not saying I’m … I’ve admitted 200 times that my paper could have done better, but I think that’s too easy an answer. And I think that answer denies that millions of Americans voted for him, most of whom don’t read the New York Times, by the way.

I think if we don’t stop and say, “What were the forces that drove this election?” And if we convince ourselves the forces that drove the election were because he got a lot of television time, I think that’s missing it. I think this was larger than that. I think this was a country that was anxious about the economy, anxious about what they thought was was a social change driven by the coasts. I think this is a country that feels disaffected by the coast. I think this is a country that was more divided than we know. I think that Fox News contributed to that division, but the division was there and they walked right in. I think if we get so caught up in Donald Trump, one, because not enough stories were written about X, tons of stories were written about X. I think Donald Trump won because there was something going on in the country that we didn’t understand and still probably sort of don’t quite understand.

Ed Wasserman: It’s been suggested that the mainstream press, of which the Times is the most authoritative, did Trump a tremendous favor in its search for even handedness in the way it dealt with the complaints and the criticisms of Hillary Clinton because so much of what was written about Trump was critical, because he was doing so many things that deeply deserve criticism. There was a sense that to balance the ledger, equivalent weight needed to be placed on sins that were incomparably less egregious in order to avoid the criticism that the ledger was being was being put in imbalance in Trump’s disfavor.

Dean Baquet: Yeah, I have a sort of a complicated answer to that. I do think that structure has not always served as well. At the right moments in American history, that structure’s been blown up. Go back and read the coverage of of Vietnam, and if you read David Halberstam’s front page stories in the New York Times from that era, or if you read Gay Talese’s stories about the south in the New York Times magazine, and I’m only mentioning the New York Times because I’ve studied it a lot, those were stories that just exploded the in the on the one hand or on the other hand, the moment deserved it. But I still think we fall back on it too much. I don’t think though that we overcompensated with Hillary Clinton, and whenever I say that I get booze.

You know, look, she was a person who had been in the public spotlight for a generation. There were questions to be raised about her time as secretary of state that were worth raising. We didn’t create the investigation to her emails. There was a criminal investigation or emails by the FBI. I think that if the leading candidate, if the nominee for a parties under criminal investigation, that’s a story to pursue, be pursued aggressively. I would still argue if you laid the coverage of Hillary Clinton next to the coverage of Donald Trump, I mean the coverage of Donald Trump was decidedly harder hitting because to be frank, there was more stuff to write about.

Ed Wasserman: Still we had a tremendous amount of attention paid to the server without there being any underlying allegation, that there was a compromise of national security. Then, the DNC email hacking, which was nothing but embarrassing, it really exposed and illuminated nothing. But, overall, the cumulative weight of that was to cast a shadow over her honesty and integrity.

Dean Baquet: I mean, it wasn’t. First off, the hacked … I mean the stuff, Podesta’s hacks, there were revelations in there. I mean there were revelations about her speeches. There were revelations that I don’t think were insignificant. Oh, all that’s been lost with the passage of time. But they were revelations about her speeches, her private speeches to wealthy business people, and what she said to them. The most powerful criticism of Hillary Clinton, as was with Bill, was that, I’m not saying this is criticism I buy, but it was criticism that was public, which was that they liked being around wealthy people. Do I think that, do I think that that was in the class with the stuff we revealed about Donald Trump? Of course not. And I don’t think that was the case at all. I don’t think so at all. No.

If I can add one thing, of course, I mean now, now we get into the great flawed journalism.

Ed Wasserman: The great flaw?

Dean Baquet: Well there are many great flaws, but there is one powerful flaw of journalism, which is that you write what you know in the moment. Of course, if we knew, if I knew that those Podesta emails were the result of a hack by Russian intelligence, possibly furthered by people in the Trump campaign, that would have been a much better story than, than the other. Just that just for the record.

Ed Wasserman: Granted. I was reflecting on what another six years of Trump and the White House might do to the medium. And I think it would really-

Dean Baquet: It would really exhaust us.

Ed Wasserman: Well, I’m wondering about whether there are new habits that are being developed and ,other people have written eloquently about this, and increasingly. The question is whether there are limits to adversarialism. Obviously, you don’t want to normalize behavior that you’re worried can become a fixture of our political culture. But here, this is very interesting. It’s a quote from this guy I wasn’t familiar with. His name was Michael Morel and he’s was former, an acting CIA director. Yeah, right.

And here’s the quote. It’s a little long, but “You know, when Hugo Chavez was first elected president of Venezuela in 1998 there was no political opposition of which the speak. The opposition was in disarray. There was no opposition leader to stand up and provide an alternative vision to that being pursued by Chavez. In its place, the Venezuelan media became the political opposition, and in so doing the media lost its credibility with the Venezuelan people. It was a huge loss for Venezuela. That is a risk right here in America right now. I believe that objective, fact-based journalism has never been as important as it is to the future of our democracy. But in order to be effective, journalists cannot take sides or even appear to take sides. It is only about our future.”

Dean Baquet: He’s completely right. I don’t want to be a leader of the opposition to Donald Trump. This is perhaps the hardest thing about navigating this era. A big percentage of my readers, and I hear from them a lot, want me to lead the opposition of Donald Trump. They don’t quite say it that way, but what they say is, “Why quote his tweets? Why go to his press conferences? Why not? Why not just call him a liar every day? Why not essentially just take him out and beat him up? What are you waiting for?” And I feel very … I think that would be … I agree with Mike Morrell. I think that would be the road to ruin, for a bunch of reasons. But to me the most powerful one is if you become the leader of the opposition, eventually the people who you’re aligned with come to power, right?

Eventually the people who want Donald Trump out come to power, and then you’re just their chump. No, I don’t want to be, it’s a tricky thing to navigate. We have never … I mean, I ordered the New York Times to call him a liar on the front page. We’ve never done that. It was-

Ed Wasserman: But you have done that.

Dean Baquet: We have done it, but I mean, we’d never done that before. I don’t think that the New York Times that ever used the word lie and in reference to, at the time he was the republican nominee. I don’t think we’d ever … In that moment, to not have done it would have been dishonest. I mean, the incident was, it was the birther incident. He had spent years saying that Barack Obama wasn’t born in the United States. He even said, “I hired private detectives and they’ve come back with interesting stuff.”

And then suddenly when pushed he said, “Okay, I believe he was born in the United States.” I thought, unlike some of the other things which sort of fall through the middle, are they fibs? How do you get inside somebody’s head? I thought that was clear and clean. So we used it. But the hardest thing to navigate is how do you look at your, “I’ll use the front page because it’s easiest measure.”? How do you look at your front page every day and say, “I’m covering something extraordinary. Granted. I’m covering something that’s unlike anything we’ve ever covered. Granted. But, somehow, I also don’t want the New York Times to look like an oppositional newspaper because for the long term life of the New York Times, that’s not a healthy position to be in.”?

Ed Wasserman: Don’t you think you’ve been successful?

Dean Baquet: I do think I’ve been successful, but I think it’s been really hard. Sure it is. And do I think that you and I could go to the archives of the New York Times and find days where we didn’t succeed? Absolutely. I mean the first thing I will own up to is that the beauty of newspapers, to be frank, they’re honorable and mission-driven, but they’re also really flawed. I mean, I could, I could find some doozies in the back if you want, mainly by my predecessors. But-

Ed Wasserman: Look, it’s one thing for me to pick up the paper and say, “Well, what is the idiot done today?” It’s another, it’s another thing to think that the Times editors are asking themselves the same question. And I don’t know what I would do in your shoes because, but I do know that we practice journalism, which is, it is subject to certain kinds of minutes of discourse and evidentiary limits and responsibility and all the rest of it. And I do know that there are limits to adversarialism. I don’t know what those limits are because he seems to transgress so routinely. But I think the fear here is the disempowerment of the Times.

Dean Baquet: Yeah, that’s right. The fear is the longterm disempowerment of the Times. But if I can say one thing that will give you hope, the one thing, I’m addicted to the histories of newspapers. Perhaps Donald Trump has not happened before, but incidents where newspapers had to wrestle with this stuff, that’s happened before. and sometimes they fail, sometimes not. I mean, I grew up in the south. I’ve talked about this. I think southern newspapers wrestled with their own version of this. I think American national newspapers wrestled with this in Vietnam. They did. I think they wrestled with … I mean, I find some comfort in almost every question I’m confronted with. Some predecessor has been confronted with it before. Right. How do you … Once it became clear that Vietnam was a tragedy and America was going to lose, you’re the editor of the New York Times, run that coverage. I think that must’ve been really difficult.

Ed Wasserman: So is part of the question the composition of your newsroom? Would you hire somebody for an important influential supervisory position on your editorial staff who is pro Trump?

Dean Baquet: I have never asked. Nobody ever believes this, but I’ll say it.

Ed Wasserman: Supposedly he comes in wearing a mask.

Dean Baquet: Well, first off, I would never hire anybody who wore a cap. You actually can’t ask that question. But, did I go-

Ed Wasserman: You’re usually not shy.

Dean Baquet: Right. But did I go out and find journalists who’d been in the military? Yes. Do I go out and try to find journalists who don’t have the same backgrounds as traditional New York Times reporters? Do I try to find journalists who I can at least … Because I mean I think the HR department would take me out in chains if I said, “Who did you vote for?” But do I try to hire people who are from a different world where I think there’s a possibility they voted for Trump? Sure, absolutely.

Ed Wasserman: Well, you’re not actually forbidden to ask their political opinion. I don’t think that’s not a protected class under the-

Dean Baquet: No, it’s not. It’s just, if you believe that journal … I have never, nobody ever believes this, but I am surrounded by a group of deputies. I have no idea who they voted for. None. Never asked, wouldn’t ask. So it would make me uncomfortable to ask that question. But if the thrust of it is, do I want a newsroom where there are people who probably voted for Donald Trump? Absolutely. And I’d like those people to have the courage and I would like to encourage them to come into me and call me out if they think I’m doing something that makes them uncomfortable.

Ed Wasserman: Let me shift this a little bit because one of the concerns that that I have is that the focus on Trump, and I’m guilty of focusing on Trump and this conversation, the focus on Trump has diverted attention from really important substantive, let’s call it, I’ll call it harms.

Dean Baquet: I mean, I think Trump is Trump. Of course Trump distracts the press, but I’m not quite sure. I mean I don’t think there’s any shortage of stories about the tragedy of Yemen and America’s involvement in Yemen. I don’t think there’s any. I mean we maintain, have always maintained a full fully formed bureau in Afghanistan. We have spent more time covering Syria than anybody else. I’m not so sure that’s true. I do think that that Americans jump for the Trump story, but I think we work hard to make sure there’s other stuff there too. The way I think about running the newsroom, I walk in every year thinking, “Okay, there’s the Trump story.” But I also think I’ve got to find out what the other big story of the year is. The first year of Trump, it was the me too story, which was the Harvey Weinstein Story.

I think we were successful. We covered the big story that everybody was paying attention to and then we came up with the other big story that people needed to pay attention to. This year, I think it was, yes, there was Trump, but we put just as much energy in Facebook and Google and the larger questions that were being raised by the platforms. What I would say to somebody who said, “I’m worried that I’m spending too much time reading stories about Donald Trump,” what I would say is you should read a lot of stories about Donald Trump. This is a historic moment. He has transformed regulation in America. He has transformed the judiciary, and everybody may be distracted by the sort of, the stormy Daniels and the other stuff over here. You should pay a lot of attention to Donald Trump. I mean, this is a transformational moment in American political life.

This is not a, I would argue this is not like a clown show that when it’s all over, everybody’s going to go, “Phew.” I think this is a very powerful moment. I think it’s in the steak to assume, to assume that Donald Trump is not responsible for some of the large changes in the government. Whether he understands how government works and knows how to pull the machinery like LBJ did, that’s a different question. But to assume that he did not choose the trade war, to assume that he did not choose to to to make immigration a national issue, I think is to underestimate what’s going on.

Ed Wasserman: Let me shift a little bit. The Times has done some remarkably good investigative work. What I want to know is, one of the things that we had, journalists, always expected was that when you run a story and you’ve got them dead to rights, you get traction in a political system. There’s a way people say, “There’s going to be a prosecutor. He’s going to hold an investigation, there’ll be legislative hearings, there’ll be a whole …” There’s an echo. Somebody notices it and they’re going to react to it. And we’re coming out of the period now the Democrats back in Congress, this may change. But I’m just wondering how it feels to time and again breaking these stupendous stories, and then the electorate, the political system just rolls over and goes back to sleep.

Dean Baquet: So when I was at, when I was an investigative reporter for the Chicago Tribune, I did a bunch of stories along with some colleagues about corruption in the government. It’s all we did. Nothing ever happened. I want spent a month investigating an Alderman who made every supermarket in his ward carry his soft drink. And I worked to prove it. I got all these people telling me all this anonymous stuff. I went to every supermarket, I counted the bottles. And I went to him and I said, “So my investigation shows that you have all these soft drink bottles, et cetera, et cetera.” And he said, “Oh yeah. No, what I do is, I make the supermarkets carry my soft drinks, and what I do is I tell them if they don’t carry my soft drinks, they’re not going to get zoning changes. Yeah, that’s what I do.” And I’m sitting there thinking, “Why did I spend a month doing this? I should have just called you after.”

After I would do those stories nothing changed. One of the guys who had wrote about 10 stories about, and I left Chicago in the ’80s got indicted two weeks ago. So I would go on panels with the, with the investigative reporters for the Minneapolis papers and I would get in here and you know the guys I was writing about were like stuffing people in trunks. They would write about guys who, politicians who like wrote the wrong name on their expense accounts and there were huge scandals.

So that I have come to believe that you do the work. Yes. It bothers you that it doesn’t have impact, or that it has, my own belief is that things have longer term impact. They’re like dropping a little bit of food coloring in the water and eventually the water changes color. But I think if you just do it for the impact, you’re gonna make yourself crazy. So you do it for the craft. You do it because it’s the right thing to do. And if you are expecting dramatic impact … I mean the Harvey Weinstein Stories, I remember just before we publish them thinking, “This is going to be a pretty good story. Nobody’s heard of Harvey Weinstein. I mean this would be good.” But who would have thunk that that created a national movement. So you never know. You do the work.

Ed Wasserman: I want to change the subject kind of almost entirely. So let’s just imagine a hypothetical under which there’s an asteroid heading towards the earth and it’s going to hit in a year’s time.

Dean Baquet: So I have time to put people in place to cover.

Ed Wasserman: So there is a possibility of deflecting it. Possibility of destroying it, in part a possibility of mitigating the harm. There’s huge preparations that are needed because depending on where it hits, different people will be impacted in different ways. There is basically only one story. That story is the asteroid, but I actually believe what I’m about to say is true, which is that I don’t know that we’re so far from that now with respect to climate change and I’m just wondering whether you’re satisfied.

Dean Baquet: You know, I don’t, I don’t want to say, boy, I don’t want to sound like a PR guy for the New York Times, but I guess it’s part of [inaudible 00:26:38]. I mean, we devoted a whole issue of the magazine and climate change. We’ve done three full special sections. Do I think we should do even more? Yes. Because I think it’s the story of our time. Yes. I think, I think we have done a lot. I think we’ve done more than anybody else. I’m past being frustrated with an end when an investigative story doesn’t have impact because I’ve learned. I’m frustrated that the, the constant drum beat of large ambitious coverage about climate change does not seem to move the discussion. I agree with that. And I guess when I hear the question, it makes me want to turn up the volume even more. I mean the volume is pretty high for us, but maybe it should be even higher.

Ed Wasserman: I’m going to ask you one more question and then open up to the floor. I’d like to hear you talk a little about the rest of the news media. What do you think they’re doing wrong? The time, not only survival but its success has been remarkable, but it’s also sort of a little bit by itself and it’s sort of benefited from a flight to quality. It’s benefited from the destruction of the regional newspaper business. What is it that people elsewhere in the media are failing to learn from you and, and can you be doing something to help them?

Dean Baquet: Yeah, well the biggest, I mean I’ll run through the biggest crisis, is local journalism. I don’t know what the answer is going to be for local journalism. I mean, I think local newspapers in the next two … I think we’re at the moment, and I think over the next two to three years, a lot of local newspapers are going to go out of business. I don’t know how anybody’s gonna make money or what the model is for covering the parts of New Orleans I grew up in, or Newark, or you know. That to me is scary and it’s the most troubling part about the plight of … the New York Times will be fine.

I worry a lot more about the Newark Star Ledger and the Miami Herald and, and I don’t think we’ve come up with another way to cover schools in Miami, and those papers have already been gutted. We are having a very interesting intellectual discussion about how the New York Times manages this, this very compelling time. But I have a newsroom of 1500 people bigger than it’s ever been. And then I go to visit local newspapers and they’re down to the bone. And I think that’s a crisis. Other papers, I mean I think Fox News is dangerous. I’ve said it before, I’ll say it again. I don’t think Fox and Friends is journalism, and I think it’s dangerous and I think they have outsized power because they happen to speak directly to the president. And I think what they practice is an odd kind of propaganda.

And I’m not saying that because they’re regarded as right wing media. I think it’s dangerous. I think the way they sort of push facts aside, I think, I think that’s scary for the country. I think the Washington Post is, if you want me to run through the list, I think the Washington Post is doing great stuff. I think the combination of the arrival of Jeff Bezos, a very good editor, I think they’re doing great.

Ed Wasserman: So I’m going to just take the interlocutors privilege and ask you one concluding question. You’re reaching that point. There’s a mandatory retirement age at the Times, I understand, of 65.

Dean Baquet: Not for everybody. The masthead has to step down at 65.

Ed Wasserman: So you can take a pay cut and stay around?

Dean Baquet: No, no, no. Traditionally the executive editor leaves the building at 65, which I will do.

Ed Wasserman: Okay, so…

Dean Baquet: But that’s 30 years from now.

Ed Wasserman: So what do you want them to say about you on your way out the door? What’s your legacy?

Dean Baquet: Oh boy. You should never write your own legacy, right? I mean if you asked me what I feel is the thing I’m proudest of at the New York Times, I do think that in the last couple, three years we truly became a publication that understood how to take advantage of all the innovations that were laid in front of us. And I think for too long newspapers, but I’m speaking of mine, looked at all of the innovation, all the possible innovations and looked at them and got nervous. And I think we’re now at the point where if somebody comes to me and says, “Dean, we have this thing and it’s just going to make storage round and they’re going to do this amazing thing, but they’re going to show people what life is like in Yemen,” I’m going to say yes, and I think that’s what I would like to have accomplished. Others will have to tell me whether I did, but that’s what I would hope to have accomplished.

Ed Wasserman: Well, Dean Baquet, thank you very much.

Dean Baquet: Thank you, thank you. Thank you.

Ed Wasserman: We’ve been listening to Dean Baquet in conversation with yours truly, Ed Wasserman. This has been On Mic, a podcast presentation of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. Technical facilities for On Mic are underwritten by the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation. Our producer is Luis Hernandez. I’m Dean Ed Wasserman. Thanks for listening and please join us next time.