What drives Yellowstone’s massive elk migrations?

Study finds elk have the means to adapt to changing climate cues, but migratory shifts may have unknown ripple effects throughout the region

June 14, 2019

Every spring, tens of thousands of elk follow a wave of green growth up onto the high plateaus in and around Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks, where they spend the summer calving and fattening on fresh grass. And every fall, the massive herds migrate back down into the surrounding valleys and plains, where lower elevations provide respite from harsh winters.

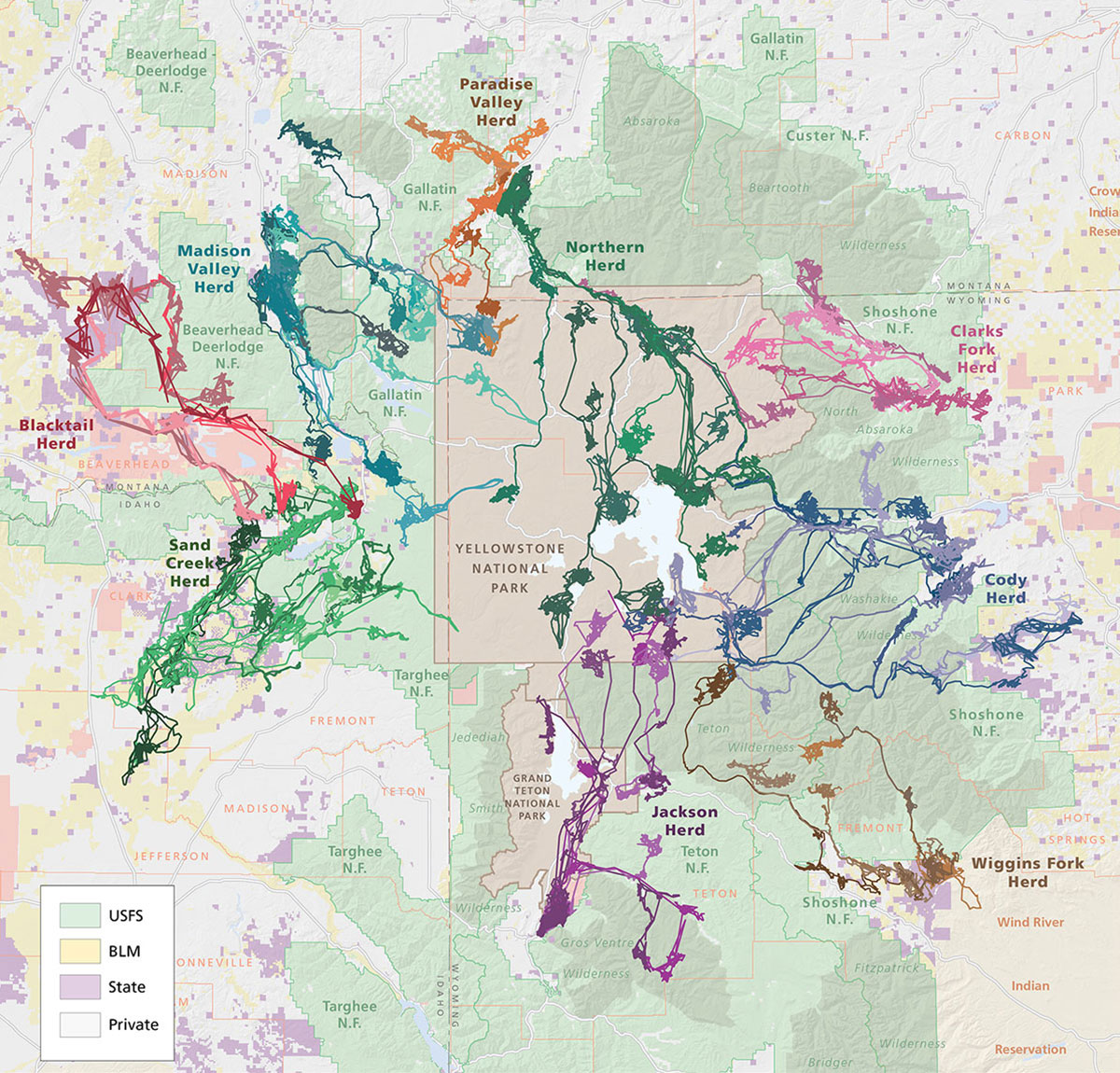

These migratory elk rely primarily on environmental cues, including a retreating snowline and the greening grasses of spring, to decide when to make these yearly journeys, shows a new study led by University of California, Berkeley, researchers. The study combined GPS tracking data from more than 400 animals in nine major Yellowstone elk populations with satellite imagery to create a comprehensive model of what drives these animals to move.

“We found that the immediate environment is a very effective predictor of when migration occurs,” said Gregory Rickbeil, who conducted the analysis as a postdoctoral researcher in Arthur Middleton’s lab at UC Berkeley. This is in contrast with some other species, such as migratory birds, which rely on changing day length to decide when to move, Rickbeil pointed out.

The new study analyzed the migratory patterns of the nine major elk populations of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, using GPS tracking data of more than 400 elk provided by a variety of state, federal, and non-profit organizations. (Map courtesy of the Wyoming Migration Initiative and the University of Oregon Infographics Lab, with data provided by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department; Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks; Idaho Fish and Game; National Park Service; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Wildlife Conservation Society; Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit; Iowa State University and Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.)

The results, published in the current issue of the journal Global Change Biology, suggest that, as climate change reshapes the weather and environment of the park, elk should have the means to adjust their migratory patterns to match the new conditions.

While this adaptability may benefit the survival of the elk, it may also have unknown ripple effects in local economies and throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem — one of the last remaining large, nearly intact ecosystems in Earth’s northern temperate zone, which encompasses about 18 million acres of land managed by more than 25 public and private entities.

“The decisions that these animals make about when to migrate are absolutely dependent on changes in the landscape, changes that are ultimately governed by the climate,” said Middleton, an assistant professor of environmental science, policy and management at UC Berkeley and senior author on the study. “And in the future, with climate change, we should expect the timing of these mass movements to be altered, which will affect the other wildlife and the people who depend on them, including predators, scavengers and hunters across the ecosystem.”

A recent UC Berkeley-led study suggests that climate change is likely to hit National Parks harder than other areas of the country. And though the study period was too short to say whether or not climate change is already affecting migratory timing, the tracking data did reveal a surprising trend: Elk on average arrived on their winter ranges 50 days later in 2015 than in 2001. This change had been noted by wildlife managers in the area, but had yet to be quantified on the ecosystem scale until now.

“This [study] provides great insight into the adaptation strategies of elk to climate change in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem,” said Jonathan Jarvis, former director of the National Park Service, who now serves as executive director of the Institute for Parks, People, and Biodiversity at UC Berkeley.

“The maps clearly demonstrate the need to think and operate at the landscape scale,” Jarvis said, “For the park managers, this kind of research gives them options and incentives, such as protection of migration corridors and seasonal habitats, for ensuring elk and other keystone species in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem will persist.”

Eating and being eaten

Yellowstone’s approximately 20,000 migratory elk are among the most important large mammals in the ecosystem, comprising about 10 million or so pounds of animal biomass pulsing in and out of the parks and adjacent wilderness areas each year — so where they can be found at any given time matters to both animals and humans alike.

“These elk eat a lot of things, and they are eaten by a lot of things, so wherever these masses of hundreds or thousands of elk are on the landscape determines who gets to eat and who doesn’t,” Middleton said. “In some cases, this could be sensitive populations of carnivores, like grizzly bears or wolves, and on the human side, it could be hunters, some of whom are making their income as outfitters and guides.”

A GPS collared cow elk climbs a hillside on the migration trail near the South Fork of the Shoshone. (Joe Riis photo)

Recent studies have shown that threatened grizzly bears depend heavily on newborn elk calves as a food source in spring — right when the migration is happening — and that a Yellowstone wolf kills, on average, 16 elk per year. Meanwhile, each fall, thousands of hunters from around the country pay guides for the chance to harvest an elk in the wilderness near Yellowstone.

While a smattering of studies has investigated the migration of individual herds in the park, none before this study had investigated the phenomenon on an ecosystem scale. To get a more complete picture of migration, Middleton partnered with state and federal wildlife managers in the Yellowstone region to pool information on 414 elk across nine herds that had been fitted with GPS collars between 2001 and 2017.

Rickbeil then analyzed the data to pinpoint when each elk made its trek from winter range to summer range and back again and used satellite images to infer the conditions on the ground during journeys.

He found that elk tended to leave their winter ranges and set out to their summer ranges as soon as the snow had melted and during the “green-up,” when fresh, nutritious plant growth began to sprout. Likewise, encroaching snowfall and hunting pressure cued them to make the return journey.

The team was surprised by the extent of the elks’ flexibility: One year, an individual female might migrate in April, but the next year in July, depending on the timing of snowmelt and green-up.

“They’ve got a big brain and big eyes, and they can look around and, to a large degree, see changes on the landscape and react to them,” Middleton said.

However, Rickbeil notes, the snow cover and vegetation couldn’t fully explain why the elk are now arriving so much later at their winter ranges. Variations in snow depth, which cannot be inferred from satellite data, might explain part of the dramatic change, Rickbeil said.

Alyson Courtemanch, who manages the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem’s Jackson elk herd as part of her job as a wildlife biologist with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, says knowing the whereabouts of the elk is critical to her job setting hunting seasons and managing the spread of diseases among wild elk and domestic cattle.

Elk pick there way along a mountainside. (Joe Riis photo)

“We’ve been observing a lot of really interesting changes over the past decade about the way that elk are moving across the landscape, specifically of the timing of the migrations,” said Courtemanch, who supplied GPS data on the Jackson herd for the study. “This analysis helped confirm a lot of things that people on the ground had suspected were happening, but that weren’t really quantified.”

“It seems like these animals can adapt to changing climates, which is likely a good thing,” Rickbeil said. “But there will be a lot of consequences to these changes.”

Study co-authors include Jerod A. Merkle of the University of Wyoming; Greg Anderson, Douglas E. McWhirter and Tony Mong of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department; M. Paul Atwood of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game; Jon P. Beckmann of the Wildlife Conservation Society; Eric K. Cole of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Sarah Dewey and David D. Gustine of the National Park Service; Matthew J. Kauffamn of the U.S. Geological Survey and Kelly Proffitt of Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks.

This research was supported by the National Geographic Society, Grant WW‐100C‐17; the Knobloch Family Foundation; the George B. Storer Foundation and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation.