Barry Stroud, influential, independent-minded philosopher, dies at 84

His overarching legacy was an ability to see the big picture in philosophy

August 21, 2019

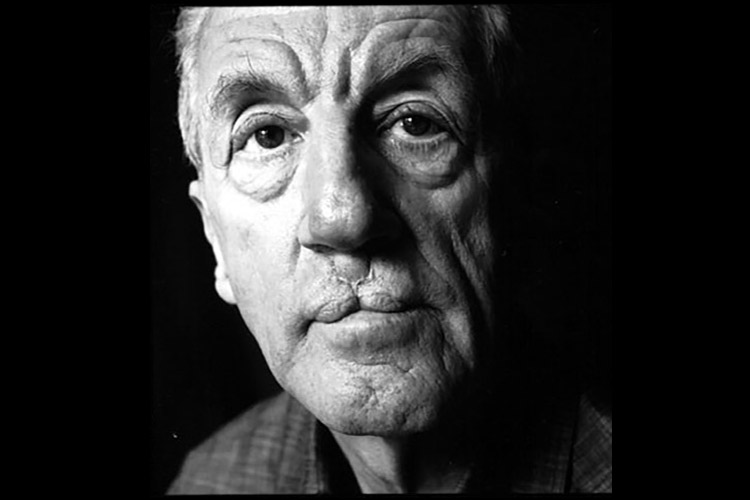

Philosopher Barry Stroud, who died Aug. 9, 2019. (Photo by Steven Pyke)

Barry Stroud, an influential thinker who challenged the prevailing attitudes of mid-20th century philosophy and sought to understand enduring and inescapable questions about knowledge, perception and reality, died of brain cancer at his home in Berkeley on Aug. 9. He was 84.

The Willis S. and Marion Slusser Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, and mentor to generations of scholars, Stroud joined the university’s faculty in 1961, after earning a Ph.D. from Harvard, and continued to teach and write even after his retirement in 2016.

While best known for his work in epistemology and philosophical skepticism — as well as his writings on such philosophers as David Hume and Ludwig Wittgenstein — Stroud’s overarching legacy, his colleagues say, was his ability to see the big picture and get to the heart of philosophy.

“Barry Stroud was a philosopher’s philosopher,” said Niko Kolodny, chair of philosophy at UC Berkeley. “He had a profound and far-reaching influence on generations of philosophers — above all, for his view of what philosophy itself was. He helped to revive an understanding of philosophy as a unique and distinctive enterprise.”

Janet Broughton, a UC Berkeley philosophy professor emerita and executive dean of the College of Letters and Science, described Stroud as a consummate philosopher perennially engaged in the life of the mind.

“Toward the end of his life, Barry was hard at work developing his views about perceptual knowledge, right up until the time his final illness made that impossible,” she said. “And even then, when he could no longer write, he took great pleasure in talking with his friends and students about the philosophical ideas to which he had dedicated so many decades.”

His seminal writings include Hume (1977), The Significance of Philosophical Skepticism (1984), The Quest for Reality (2000), Engagement and Metaphysical Dissatisfaction (2011), and four volumes of collected essays including Seeing, Knowing, Understanding (2018).

A provocative thinker

As a philosopher, Stroud came of age during a time when the prevailing Western attitude was that philosophical questions could be answered by the natural or social sciences, and he challenged those ideas, colleagues said.

“Writing against these currents, Barry showed that the deepest questions philosophy asks — ‘What underlies our conception of the world and of ourselves within it?’— were distinctive, and had to be answered in distinctive ways,” Kolodny said.

“One might say that, while everyone else was philosophizing about consciousness, reality and knowledge, he was philosophizing about philosophizing itself,” he added.

Jason Bridges, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Chicago and a former Ph.D. student of Stroud’s, echoed that sentiment.

“Barry single-handedly brought philosophical skepticism — which gives reasons to doubt whether we can know even the most ordinary things about the world around us — back to the center of philosophical discussion,” Bridges said.

A native of Toronto, Canada, and a lifelong Canadian citizen, Stroud was more than a philosopher to his three daughters, Sarah, Martha and Julie.

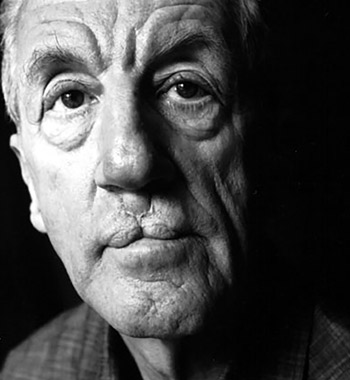

“Barry Stroud. Son. Brother. Farmhand. Point Guard. Quarterback. East York Goliath. Telegraph Climber. University of Toronto Student. Harvard Grad Student. Professor. Philosopher. Reader. Cinephile. Runner. Traveler. Venetian. Father. Friend. 5/18/35-8/9/19. I’ll love you forever,” Julie Stroud tweeted the day after her father’s death, along with photos of his multifaceted life.

“Barry Stroud. Son. Brother. Farmhand. Point Guard. Quarterback. East York Goliath. Telegraph Climber. University of Toronto Student. Harvard Grad Student. Professor. Philosopher. Reader. Cinephile. Runner. Traveler. Venetian. Father. Friend. 5/18/35-8/9/19. I’ll love you forever,” Julie Stroud tweeted the day after her father’s death, along with photos of his multifaceted life.

His eldest daughter, Sarah Stroud, a philosophy professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, remembers her father as an avid reader, cinephile, jazz enthusiast, art lover, wine connoisseur, talented cook and passionate outdoorsman.

An athlete and laborer

Born in Toronto in 1935, Stroud was the youngest of two sons born to William Stroud, a salesman for a clothing company, and Florence Stroud. Both were from families that had immigrated to Canada from England.

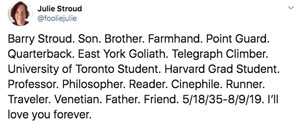

Stroud was born in Toronto in 1935. (Photo courtesy of the Stroud family)

At just age 10, he started working summers as a farmhand, operating tractors, mowers, binders and hay elevators. At 18, he left farming to work for the Canadian National Railway, stringing and replacing telegraph wire in remote areas of Ontario.

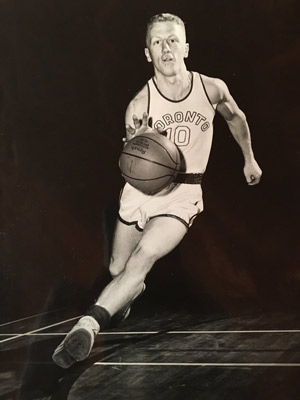

In high school and college, he was a star athlete. At Toronto’s East York Collegiate Institute, he was the starting point guard in basketball and the starting quarterback in football. Then, at the University of Toronto, where he majored in philosophy, he was a starting point guard on the campus’s Division 1 varsity basketball team.

“Through Barry’s physical prowess and athletic achievements, he cultivated a work ethic, competence and confidence that contributed enormously to his distinctive academic and intellectual achievements,” said his daughter, Martha Stroud, associate director of the University of Southern California’s Shoah Foundation Center for Advanced Genocide Research.

And that athleticism carried through into his adult life: “In addition to years of regular basketball games and low-handicap golf outings, he ran and then walked six miles a day through Tilden Park,” she said.

Stroud was a starting point guard on the University of Toronto basketball team. (Archival photo courtesy of the Stroud family)

After earning a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from the University of Toronto in 1958, he went to Harvard University on a Woodrow Wilson fellowship. There he met Janice Goldman, a doctoral student in sociology. The two married in 1960 at Cambridge City Hall.

They moved out West when Stroud was hired as an assistant professor of philosophy at UC Berkeley in 1961 and went on to have three daughters. Their marriage ended in 1979.

Lifelong Venetian love affair

In 1975, Stroud became a tenured professor, and went on to serve three separate stints as chair of the philosophy department over the next decade and a half. After several sabbaticals at the University of Oxford in England, he spent a sabbatical in Venice and fell in love with the Northern Italian city and its people.

“He promptly set out to learn Italian, a language he had never previously studied, and developed a profound love for Venice and Venetians, and traveled regularly to Venice for the rest of his life, most recently in December 2018,” Sarah Stroud said.

Over the next three decades, his academic career at Berkeley flourished as he shaped generations of young philosophers and received honors, including fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the British Academy. From 1995 to 1996, he served as president of the American Philosophical Association.

Meanwhile, his visiting professorships and guest lectures took him around the world, including to the University of Oslo, the University of Athens, National Autonomous University of Mexico, and to Brazil and Argentina.

In 2007 at Berkeley, Stroud was named the Willis S. and Marion Slusser Professor of Philosophy, a position he held until his retirement in 2016. He continued to teach and advise until weeks before his death.

In an online tribute to Stroud, John Tasioulas, a professor of politics, philosophy and law at England’s King’s College London, tweeted this:

Stroud is survived by three daughters, his brother and two grandchildren. (Archival photo courtesy of the Stroud family)

“All too often philosophers portray themselves as having it all figured out, a glibness of attitude that is starkly at odds with the difficulty and persistence of philosophical problems. One of the greatest opponents of this glibness in our day was Barry Stroud. RIP.”

Stroud is survived by his daughters, Sarah Stroud, of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Julie Stroud of Berkeley and Martha Stroud of Los Angeles; his brother, Ronald Stroud and sister-in law Helen Stroud, of Berkeley; son-in-law Daniel Hellerman; a niece, nephew and two grandchildren.

A campus memorial for Stroud will be held on Nov. 2. Details about the time and location will be posted on the Department of Philosophy’s website.