In media coverage of climate change, where are the facts?

A study of New York Times coverage of climate change shows that articles rarely present the facts behind the scientific consensus on global warming

September 19, 2019

The New York Times building in New York City.

The New York Times makes a concerted effort to drive home the point that climate change is real, but it does a poor job of presenting the basic facts about climate change that could convince skeptics, according to a review of the paper’s coverage since 1980.

Public polls show that Americans, whether agreeing or disagreeing with the idea that human activity is changing Earth’s climate, lack an understanding of the basic facts leading to this conclusion, says climate scientist David Romps, a University of California, Berkeley, professor of earth and planetary science. A large percentage of the public doesn’t know that global warming is happening now, that it’s caused by record levels of CO2 from fossil fuel burning, that 99% of climate scientists agree on this and that the changes are effectively permanent.

“If the New York Times isn’t doing it, my guess is that it is just not happening across print journalism,” Romps said. “One of the hopes is that, by at least pointing this out, it might occur to people to take a look at what kind of context is provided in news coverage of climate change.”

Romps and co-author Jean Retzinger, the former associate director of UC Berkeley’s Media Studies program, published their analysis in the journal Environmental Research Communications.

After more than a decade of research focused on how climate change affects the atmosphere — in particular, clouds and lightning — Romps became frustrated about the public’s lack of basic knowledge of the science that underlies the 99% consensus among climate scientists.

“The notion that there is a scientific consensus has been referred to as a gateway belief by people who study how the public thinks about climate change,” Romps said. “They find that, if you can get people to understand that fact, it kind of pries the door open and makes them open to learning more and potentially changing their minds.”

Yet, as of 2019, the fact of a scientific consensus is mentioned in a mere 4% of Times articles about climate change, he and Retzinger found. The fact that we are experiencing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that haven’t been seen in millions of years — and never before in human history — is mentioned in only 1% of the paper’s articles.

The percentage of climate change articles in the New York Times since 1980 that mention five basic facts about global warming. (Graphic by David Romps, UC Berkeley)

And the fact that climate change is permanent is mentioned in only 0.4% of articles.

“We are talking about an alteration of the planet’s climate, and in all of my conversations with people, no one has ever asked me how long it lasts,” Romps said. “I don’t understand how people can have any sort of opinion about global warming without knowing that fact: that it is effectively permanent. The time scale for drawing the CO2 anomaly back down to where it was 50 years ago is on the order of 100,000 years, 10 times longer than human civilization. So it is, for all intents and purposes, permanent. And each additional increment of warming is effectively permanent.”

Lack of facts sows confusion

A fourth climate-change fact he looked at — that CO2 produced by fossil fuel burning creates a greenhouse effect that warms the planet — was mentioned in only 0.1% of the articles. Many people confuse the effects of carbon dioxide with the ozone hole, which is caused by chlorofluorocarbons used in refrigerators, or think that warming is due to the heat produced by burning oil and gas.

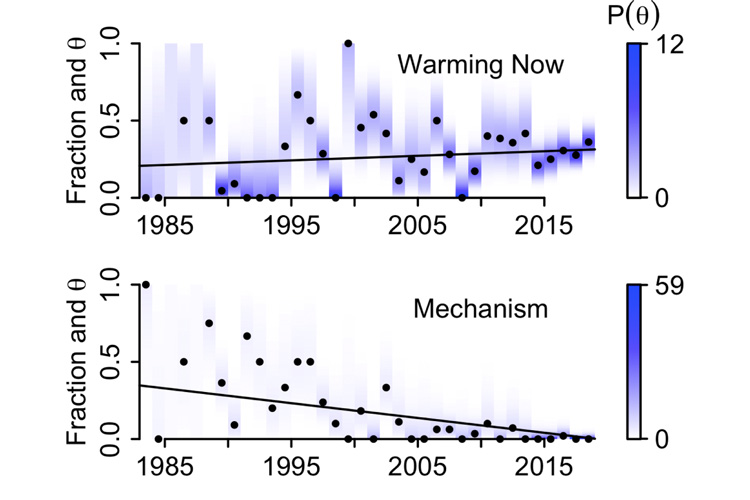

Two key facts – that climate change is already happening and that carbon dioxide from fossil fuel burning is causing it – have received the most ink in New York Times articles, though mention of the latter has dropped to nearly zero in recent years. The other three facts were hardly ever mentioned in the paper’s news articles about climate change. The dots indicate the percentage of articles containing these facts in each year, while the blue is a measure of uncertainty. (Graphic by David Romps, UC Berkeley)

His data show that, in the 1980s, when the concept of global warming was still new to many readers, the Times often referred to the mechanism of greenhouse warming and did so, in some years, in every article. But 20 years later, this mechanism is seldom mentioned, despite a whole new generation of readers.

The only fact mentioned regularly — in nearly one-third of all articles — is that the effects of climate change are being felt now. But of the 600 news articles mentioning climate change over the 38-year period, the vast majority contained none of the five basic climate facts. This occurred despite the ease with which the basic facts of climate science were embedded in articles that did mention these facts.

“We have this major problem: that people don’t seem to have a solid grasp of the fundamental ideas. And why would that be?” he asked. “There has been a well-funded campaign to spread misinformation and sow doubt about global warming, which has been very successful. On the other hand, climate scientists are not necessarily out there communicating effectively to the public.”

“After you finish school, you learn about science primarily through the news,” he added. “And if you are not getting appropriate context from that news coverage, you are going to be confused.”

Romps is embarking on an experiment to try to change this, partnering with UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism to offer fellowships to student environmental writers to discuss with climate scientists the basic facts about climate change and how best to convey them within news articles. If this proves effective in changing public understanding, it could open the door to a broader national discussion of climate change coverage in the media.

Paper of record

To assess whether the basic facts behind the scientific consensus about climate change are being communicated through the media, Romps and Retzinger focused on perhaps the number one paper of record in the nation, the Times.

The 597 climate-change articles published by the New York Times since 1980 show consistent coverage of the issue, with peaks during significant news events. (Graphic by David Romps, UC Berkeley)

“We chose the New York Times because it certainly has this reputation of being excellent in covering environmental issues and climate change, and I personally think it’s one of the best,” he said. “At the same time, I had this feeling from having read stories on climate that they didn’t convey the basic facts to readers, and that that might be a problem.”

They enlisted the help of a dozen undergraduate students to review New York Times articles mentioning climate change that were published between 1980 and 2018, in search of the key words employed when mentioning five basic facts: the consensus, mechanism, longevity, magnitude and immediacy of climate change.

They then searched for all articles that included these key words, and Romps read each one to judge whether or not it mentioned these five facts.

“I don’t think that everyone learning the basic facts I have outlined here is a solution in itself. But I do believe it is a necessary condition,” he said. “We are not going to make the progress we need until everyone from both political parties, from rural and urban areas, from all states, accept the fact that global warming is happening, it is caused by us, and that the solution is to stop burning fossil fuels. These are the basic facts that climate scientists know, policy wonks know, but somehow the broader public does not quite appreciate yet.”

In addition to his efforts to better communicate the facts of climate change, Romps hopes to set an example for those wanting to reduce their carbon footprint. Last year, he refused to fly to an awards presentation, and since January has not flown to any scientific meetings — a big drop from his typical yearly air mileage topping 100,000 miles. He’d like to deliver scientific papers to colleagues via video streaming, but this is not yet an accepted practice at annual meetings.

Nevertheless, he is heartened by younger people speaking out, and he supports the Sept. 20 worldwide climate strike, including a UC Berkeley rally at 11 a.m. in Sproul Plaza with talks by students and faculty. While Romps that day will be teaching his undergraduate course on the science of climate change, he plans to attend the rally and encourages his students to do the same.

“Being a climate scientist can be a fairly depressing occupation,” Romps said. “But seeing young people stand up and make their voices heard is really quite encouraging. There is hope. The youth have been heeding the call, and we need grown-ups to start heeding the call, too.”

This study was supported by the National Science Foundation (1535746) and the National Institute for Climate Education.

RELATED INFORMATION

- Climate news articles lack basic climate science (Environmental Research Communications)

- Romps’ Physics of Climate website