‘Triptych’ is a meditation on provocative photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s work

Robert Mapplethorpe was known for pushing the boundaries with his photos. Now, 30 years after his death, Triptych explores what his photos meant to American culture and how they're relevant today

September 24, 2019

When korde arrington tuttle was growing up in North Carolina in the 1990s, he felt like he had to live in a world with strict boundaries drawn around what he could do, and how he could act.

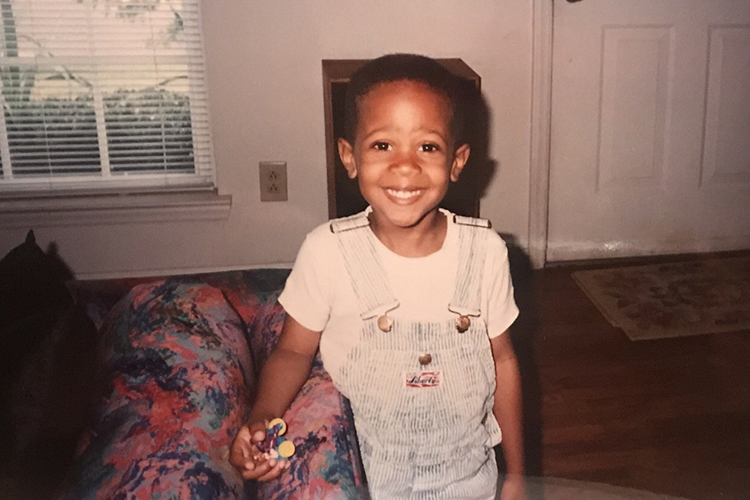

korde arrington tuttle grew up in North Carolina. (Photo courtesy of korde arrington tuttle)

His parents nurtured his creativity, but the culture he was raised in was conservative and religious. He and his five younger brothers and sisters grew up in the church, and in predominantly white neighborhoods.

“I was a faithful and devoted child,” says tuttle, “which meant internalizing whatever would allow me to continue receiving love and adoration from my parents and authority figures, structures and institutions.”

tuttle with his parents, Loretta and Perry, and his five younger siblings, Karsynn, Karigan, Kanyon, Kallaway and Kambridge. (Photo courtesy of korde arrington tuttle)

tuttle felt denied the ability to understand his sexuality as a child and teenager. As a senior in high school, he was enrolled in conversion therapy, which tries to change a person’s sexual orientation to heterosexual, through an organization called Exodus International. (It has since been closed.)

“That is one extreme, although an all-too-common example, of how censorship manifested in my life,” he says.

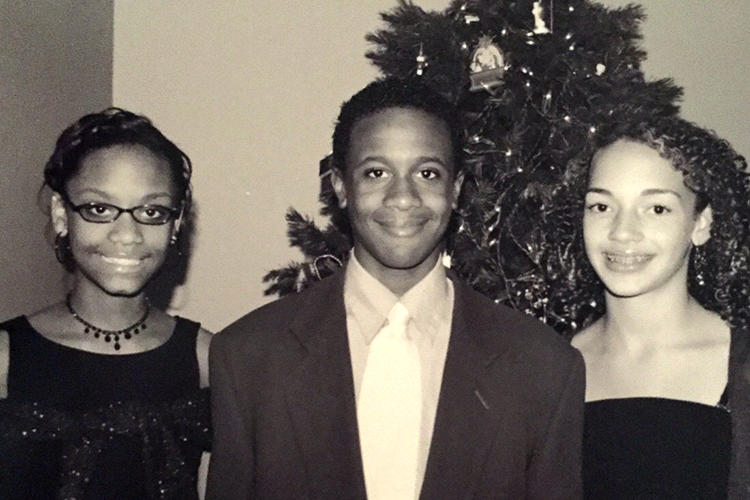

tuttle with his sister, Karsynn (left) and family friend Vanessa Watson (Photo courtesy of korde arrington tuttle)

In college, tuttle became interested in the life and work of an artist and photographer named Robert Mapplethorpe.

“I was drawn to Mapplethorpe’s confrontational gaze and spirit,” says tuttle. “I was also turned on by the images of eroticism and beauty. Although I didn’t have language for it at the time, on a subconscious level and in a deep emotional way, Mapplethorpe’s composition, his relationship to religious iconography and sacred geometry, spoke to something I recognized.”

Robert Mapplethorpe’s eyes in Triptych (Brooklyn Academy of Music photo by AA Baranova)

Listen to an excerpt from Triptych.

Now in his 20s, tuttle has written a libretto for an oratorio called Triptych (Eyes of One on Another). A libretto is text used in a long vocal work, and an oratorio is a large musical composition for an orchestra, choir and soloists.

Created by composer Bryce Dessner, of the rock band The National, and co-commissioned by UC Berkeley’s Cal Performances, Triptych is a mixture of music, words, images and video that reflects on the impact of Mapplethorpe’s provocative photography. It’s performed by vocal ensemble Roomful of Teeth, along with mezzo-soprano Alicia Moran, actor Isaiah Robinson and the San Francisco Contemporary Players.

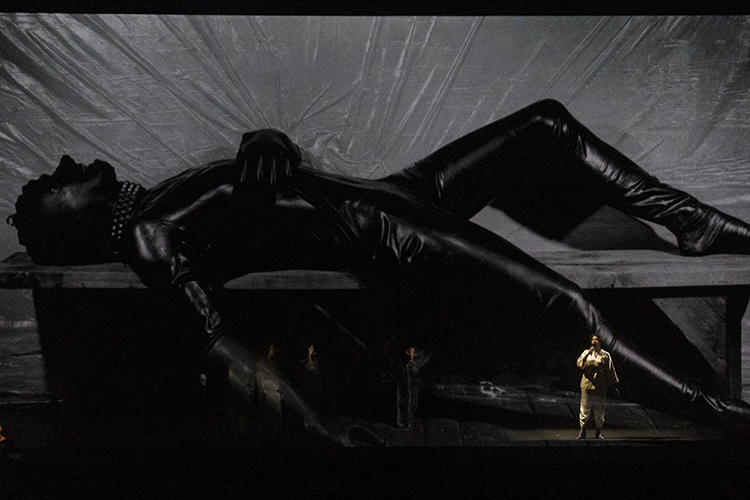

Actor Isaiah Robinson in Triptych (Brooklyn Academy of Music photo by AA Baranova)

Singer Alicia Moran in Triptych (Brooklyn Academy of Music photo by AA Baranova)

“I would describe Triptych as a conjuring, drawing from the well of dramatic, theatrical, musical and obviously operatic, photographic, video, graphic, choreographic traditions,” says tuttle. “It is inspired by the life, death and legacy of artist, mystic, prophet Robert Mapplethorpe in conversation with poet, activist, philosopher, agitator Essex Hemphill and luminary Patti Smith.”

Mapplethorpe was born in 1946 in Floral Park, a suburb of New York City. In 1963, he enrolled in the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where he studied drawing, painting and sculpture. He met musician and poet Patti Smith in the mid ‘60s, and the two moved into the Chelsea Hotel.

Triptych (Brooklyn Academy of Music photo by AA Baranova)

He began taking Polaroid photographs in 1970, and a few years later, upgraded his camera. His photography was diverse and often unexpected, united by a formal photographic approach and technique.

His work included nudes — many of black men, self-portraits, still lifes of flowers and celebrity portraits. His most controversial work at that time was of the bondage, dominance and sado-masochism, or BDSM, subculture in New York City.

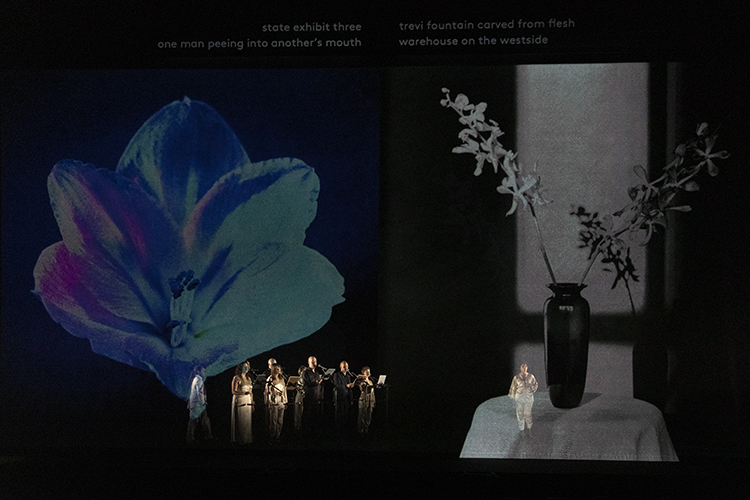

Triptych (Brooklyn Academy of Music photo by AA Baranova)

In 1989, when Larry Rinder, a curator at the University Art Museum — it was since renamed the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, or BAMPFA — was asked if it should display photos by Mapplethorpe in an exhibition called The Perfect Moment, Rinder said “no.”

Rinder, now the museum’s director and chief curator, had just started working at the museum. He’d come from New York City, and had specific ideas about what art was — and what it wasn’t. He thought of art as a way to call power into question, to challenge the status quo. And he didn’t really think that Mapplethorpe’s work did that.

But the museum director at the time, Jim Elliot, felt differently.

And somehow, in the moments it took Rinder to make his way back to his office, Elliot had slipped the materials with a note onto the curator’s desk.

“And it said, ‘Congratulations, you’re in charge of the show.’ So it was a very rapid lesson in how, when you work at a museum, the museum is bigger than you are, and you kind of serve a greater good,” says Rinder.

The Perfect Moment, a collection of Mapplethorpe’s photos, was shown at UC Berkeley’s art museum in January 1990. (BAMPFA photo)

“And I think it was a healthy thing for me because it really did get me out of my habitual ways of thinking. Having to be responsible for the Mapplethorpe show, I think, opened my eyes to a different way of thinking about the relevance of art and the complexity of art — the balance between beauty and challenges to taste.”

The Perfect Moment, a collection of 175 of Mapplethorpe’s photographs, was cancelled by the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. in June 1989, amid congressional arguments about what type of art should receive federal funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. Protests followed, and the director resigned.

So, showing this work at that time was a political statement, says Rinder. One that was risky for the museum to exhibit.

The Perfect Moment at BAMPFA in 1990 (BAMPFA photo)

“I think that today, it’s hard to imagine how politicized culture was at that particular moment,” he says. “It was, you know, a very intensely highly charged moment.”

It was at the height of the AIDS crisis — Mapplethorpe had died from the disease months before, in March 1989, at age 42.

And, it was the beginning of the so-called culture wars — when American society was becoming more and more divided between traditionalists and progressives over issues including abortion, homosexuality, gun laws, immigration, LGBT rights and censorship.

“That was an additional potency that the exhibition had at that moment,” says Rinder. “A potency of the personal tragedy of Mapplethorpe. But also, of social and community tragedy, because what happened to Mapplethorpe was happening to others on a daily basis, particularly in this area. So, the exhibition became a kind of concentrated experience of a lot of very intense currents that were coursing through the community at that particular moment.

“And I do think that art has the capacity to be a kind of lightning rod for the most important issues of life, and that exhibition was certainly an embodiment of this.”

Triptych (Brooklyn Academy of Music photo by AA Baranova)

In January 1990, The Perfect Moment opened at Berkeley’s art museum, where it was positively received, says Rinder. The only negative feedback he recalls receiving was a letter from the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights.

“Looking back, there was a fearful atmosphere around AIDS,” says Rinder. “There was obviously the tragedy of so many people passing away. But there was also a fear of contagion. I mean, we were living in the time of a plague. There was so much negativity being projected onto sexuality and Mapplethorpe’s work unabashedly celebrated the body, sex and gay sexuality, in particular. So, I think the show helped change people’s perception of themselves and others in a positive way.”

The exhibit went on to be shown at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center in April 1990. Hamilton County prosecutors in Ohio charged the center’s director Dennis Barrie and the museum with obscenity. It was the first time criminal charges had been brought against a U.S. museum.

Although some critics say that Mapplethorpe’s work has lost its relevance today, Rinder says it still presents a dynamic where viewers are pushed into a space between reality and possibility, or between the real and the ideal.

Triptych (Brooklyn Academy of Music photo by AA Baranova)

And Triptych librettist tuttle has found an inspiration in Mapplethorpe’s work that helped him begin to break out of the invisible boundaries he felt imprisoned by as a youth, and to create daring work on his own terms.

“I loved and admired that he seemed to do whatever he wanted to do, how he wanted to do it, when he wanted to do it,” says tuttle. “He was not bound by the lines that were drawn around him, which is something I didn’t feel I had permission to do.

“There was an honesty about the pain and pleasure unified, explained, unexplained in his work that I appreciated and that I was inspired by. I appreciated allowing it all to co-exist without explaining it, and I felt like that provided me the opportunity to do my own work and make up my mind for myself.”

Triptych (Brooklyn Academy of Music photo by AA Baranova)

Triptych will make its Bay Area debut at Zellerbach Hall on Saturday, Sept. 28, at 8 p.m. The performance will run one hour and 10 minutes without an intermission.

Cal Performances has planned related events on campus, including a panel discussion on making meaning from the marriage of new music, performance and imagery with Berkeley professor of photography Liz Linden, librettist korde arrington tuttle and musician and scholar of sound and meaning, Serena Le. There will also be a master class for the UC Choral Ensembles taught by Roomful of Teeth and a post-performance group discussion with audience members.

To buy tickets or learn more about Triptych and its campus events, visit Cal Performances.