A Day of the Dead exhibit, to remember

Joyful Día de los Muertos altar exhibit opens Thursday in Wurster Hall

October 31, 2019

Ruffled marigolds, handmade of paper by psychology major Erika Ramos, and fresh marigold stems help form a heart-shaped border around her Día de los Muertos altar in Wurster Hall. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

Undergraduate Erika Ramos’ altar is heart-shaped, with handmade paper marigolds, a coin-filled shoe and a hummingbird atop a white paper rose. Bianca Ramirez, an art major, made ceramic versions of pan dulce, or Mexican pastry, and cacti for hers. The altar built by their classmate, Laura Diaz, includes a notebook and pen, a pineapple, mangoes, framed photos of her grandfathers and colorful rectangles of perforated paper, papel picado.

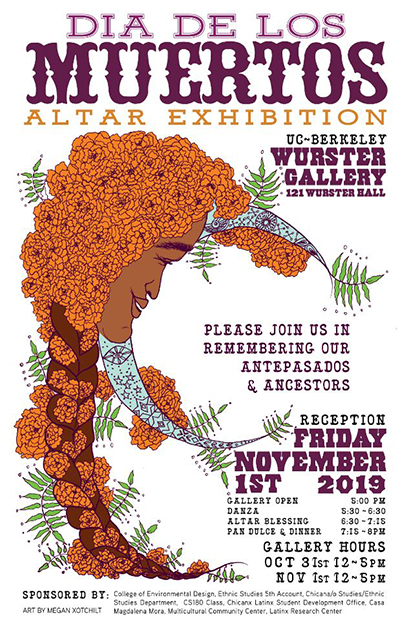

A poster invites the campus community to join the Día de los Muertos activities Oct. 31 and Nov. 1 at Wurster Hall.

These altars are just a few of about 45 at the campus’s annual Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) Altar Exhibition in UC Berkeley’s Wurster Gallery. The gallery, in 121 Wurster Hall, will be open to the campus community both today (Thursday, Oct. 31) and Friday, Nov. 1, from 12 noon to 5 p.m. On Friday, festivities begin at 5 p.m. and feature food, Mexican dancers and an altar blessing.

Día de los Muertos originated in pre-Hispanic cultures, which considered it disrespectful to mourn the dead and, instead, kept the departed alive in memory and spirit. Today, the festival is a combination of indigenous and Catholic rituals that unfolds in many parts of Mexico on Nov. 1 and 2 and includes costumes, make-up, parades, parties, singing, dancing and offerings to lost loved ones. Decorated altars, or ofrendas, in cemeteries and in homes often contain bright, pungent marigolds, which are said to guide spirits to their altars.

Jesús Barraza, a campus lecturer in the Department of Ethnic Studies, says the Día de los Muertos event at Berkeley began in the early 2000s and attracts several hundred visitors. Designing the altars is a major project for students in his Chicanx studies class, “Spirituality as Resistance: The Politics of Day of the Dead in Mexicana Art Practice and Culture.”

The Wurster Gallery is readied for the exhibit that, starting Oct. 31, showcases some 45 altars created by students and others in the campus community. (UC Berkeley photo by Violet Carter)

“In some areas of Mexico, a big part of Día de los Muertos is the tradition of people going to the cemetery, cleaning it up, leaving flowers and preparing space for the dead to come back. People also have altars at home,” he says. “But here in the U.S., with people having migrated from Mexico for one or more generations, survival has often been the biggest part of life, and previous customs might not be passed on. People have left home and sometimes have no chance of going back. My hope is that this is a way for students to connect with their culture.”

The yearly altar-building also is open to groups that help sponsor the event, like the Chicanx Latinx Student Development Office, the Multicultural Community Center and the College of Environmental Design (CED).

The altars are a major project for students in lecturer Jesús Barraza’s class, “Spirituality as Resistance: The Politics of Day of the Dead in Mexicana Art Practice and Culture.” (UC Berkeley photo by Gretchen Kell)

“It’s a wonderful chance for our staff to connect on a different level and for us to celebrate the lives of those we’ve loved and lost,” says Mike Bond, CED’s facilities director. He says he’ll add to the CED altar the jacket his uncle wore “almost every day toward the end of his life. …When I put it on, it makes me feel like he’s still here, giving me a hug.”

Barraza says the art of creating Día de los Muertos altars is a healing activity. In his class, he uses the text Light in the Dark, Luz en Oscuro, by Gloria Anzaldua, which explores how “art can make us whole again” after experiencing trauma, including the anguish of leaving one’s homeland and being separated from ancestors and traditions.

Erika Ramos’ altar includes a photo of her grandfather’s sister, who took care of Ramos when she was young. Ramos says she believes the woman visited her, after death, as a Monarch butterfly during a wedding. Ramos wrote words from the song “Amor Eterno” (Eternal Love) on the frame. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

“Unless we’re Ohlone, we’re all migrants here, whether from Europe, China, Mexico or South America,” he says, adding that his students are from all over the world. “Those stories are tied up with trauma. As my students explore that, those personal migration stories come up, and they deal with family — that’s a big part of Día de los Muertos — and get the opportunity to tell their truths” through art.

Ramos, a psychology major, says Barraza’s class “brought me closer to my family.” Having lost her maternal grandmother just this year, she says she learned in class to better understand grief “and to be OK with it. In Mexican culture, families don’t often talk about death.” Her family, from nearby Pittsburg, never made a Día de los Muertos altar, but Ramos says she hopes they’ll attend the Nov. 1 event.

A student tidies her altar for the Wurster Galley exhibit. In Mexico, families clean and decorate the graves of loved ones to welcome their spirits. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

Barraza says the students’ unique and thoughtful altars are proof they’re discovering “how to incorporate art into their lives. Many times, in my class, students, whether they’re majoring in English or computer science, find they are very artistic.”

Ramos’ altar includes a white rose, like the kind at her grandmother’s funeral, and a candle for her fraternal grandmother. For her grandfather’s sister, Ramos placed faux Monarch butterflies on her framed photo, since, after her death, “a Monarch landed on my eye at a wedding. I felt that was her” paying a visit. Coins in a shoe recalls her maternal grandfather, who she says “always put money in his 35 grandkids’ shoes” on Christmas Eve. Her paternal grandfather is remembered with his favorite American candy, peppermints, and a replica of a hummingbird — a bird he loved to watch.

Bianca Ramirez, an art major, crafted prickly pear cacti and pan dulce from clay for her hand-built altar, which she says she plans to take home “and keep forever.” (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

Ramirez, a fourth-year student, built her own altar out of wood and tile. “I wanted an altar I could take home and keep forever,” she says. The class helped her understand some issues she struggled with growing up in East Los Angeles; her ancestry is in Jalisco, but she hasn’t been there since she was 11 or 12.

“I always thought I was a fraud Chicana, pretending to know my culture,” she explains. “Now, I realize what happens with migration, when you’re far from your homeland.” She’s been reconnecting with her family, and last weekend she and some relatives went camping — an occasion for Ramirez to ask questions of her grandmother.

“I found out there are a bunch of cowgirls in my background,” says Ramirez, a potter who, like cowhands, likes to work with tools and water. She adds that her altar is dedicated to the family member in her past “who is trying to connect with me in my creative process.”

More than a few altars in the Wurster Gallery contain loved ones’ favorite foods and drinks. Treats set out for the spirits include peppermints, Mexican Coca-Cola, mezcal, pan dulce, pineapple, mangoes, dried beans and doughnuts. (UC Berkeley photo by Violet Carter)

Isela Pena-Rager, a CED undergraduate adviser, says this year’s Día de los Muertos altar exhibit is especially meaningful to her because her father died earlier this month. In looking for the right photo of him to place on the CED altar, she found an old one taken before he left Mexico for the United States.

“I’d never seen that photo before; he looks so handsome. It’s such a beautiful thing to think of him then, with his whole adult life ahead of him. He also liked pomegranates,” she says. She’ll place one on the altar, in his memory,, and also recently planted a pomegranate tree in the yard of her new home in Oakland.