Berkeley Talks transcript: Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky on defending DACA

November 22, 2019

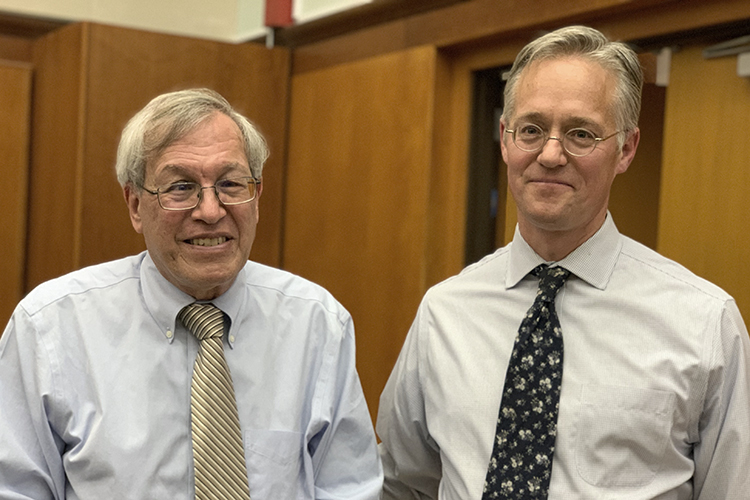

Francesco Arreaga: My name is Francesco Arreaga. I am the co-president of the Berkeley Immigration Group. Thank you all for coming. It is a great turn out. Today we will be talking about the DACA litigation that occurred in the Supreme Court last week. We have two esteemed speakers. First, Dean Erwin Chemerinsky. He is a spectacular dean at our law school, who not only manages the law school but fights for justice in our country. So thank you, Dean Chemerinsky.

[Audience applauds]

And we also have Mr. Ethan Dettmer, who is partner at Gibson Dunn. He came to our law school last year as well to talk about immigration, and he continues the fight helping immigrant communities in America, so please give a warm welcome as well.

[Audience applauds]

Erwin Chemerinsky: Thank you. Thank you so much for coming this afternoon. I’m so honored that I’ve been part of this litigation from an early stage. I’ve had the great pleasure of working with Ethan, who really spearheaded the effort at Gibson Dunn. Terrific lawyers there. Mark Rosenbaum in Public Counsel and, of course, others who are involved as lawyers in some of the additional cases that were being litigated simultaneously, and ultimately culminated last week in the arguments before the United States Supreme Court.

To set the stage from the lawyers perspective, and that’s what we’re really gonna be talking about this afternoon, is the lawyers perspective. It was very clear from the outset that these were tremendously sympathetic facts. It was a very difficult set of legal issues. All of you are familiar with the facts. This is about somewhere between 700,000 and 800,000 individuals. They were brought to the United States at a young age to qualify. They’re younger than 15. They had to be no older than 30 at the time the program went into effect. They all had to be in school. They’re successfully graduated. They have a GED, or are in the military, or honorably discharged.

The idea of deporting such individuals makes absolutely no sense, to be sending them to a place where they had never lived. It was cruel. These were individuals who rightly, from the outset, were called Dreamers. So if you think of it from a lawyer’s perspective, you could not have more sympathetic clients, you could not have a more sympathetic cause.

But it’s also clear from the outset, as a matter of law, it’s a very difficult legal issue, and this is something that has to be faced at the District Court, the Ninth Circuit, and the Supreme Court brief and oral argument. Now the most immediate argument that would come to mind would be one of reliance that these individuals had developed a liberty or a property interest

in remaining the United States, and that for President Trump to rescind DACA was taking away their liberty or property interest without due process. But if you look at the website of DACA, it made very clear they should have no reliance on the statute. They have no reliance on the president’s executive order. If you studied procedural due process, you know whether you have a liberty or property interest is based on the expectations that are created, and here, the website couldn’t be clearer, have no expectations.

At the same time, this is an area of tremendous presidential discretion. Ultimately, the reason DACA is legal is because of the discretion of the president, but then if the president has discretion to create DACA, doesn’t the president also have discretion to rescind DACA? In fact, doesn’t that create a dilemma that has to be faced at each stage of the litigation?

If DACA is illegal when it was adopted by President Obama, then President Trump is justified in rescinding it. If DACA is legal, it’s because

the president had discretion, but if President Obama had discretion, doesn’t President Trump have discretion to rescind it? And I think another way to agree on this, this was the central difficult legal issue that’ll be faced at each stage of the litigation.

Ethan Dettmer: So just to follow up on what Dean Chemerinsky said, I mean, the themes that he was just mentioning came out in incredible detail and really powerful advocacy in questioning at the argument last week in the Supreme Court, and this is really a theme that we dealt with throughout the entire case. Now what we’re gonna try to do, just give you a little roadmap for the day.

We’re gonna try to step back to before the beginning of this case, give you some background on what this is about, give you a little sense of what it’s like to litigate a case like this, although, cases like this are all very different. And then we’re going kind of march through the litigation itself and end up in the Supreme Court and talk about what happened last week.

So we’re being ambitious, we’re trying to do a lot, but we’re gonna try to save some time at the end for questions as well. So here’s just a little audiovisual for you on what we had here.

Erwin Chemerinsky: And he prepared all the slides. I don’t know how to do PowerPoint. So he gets full credit for this wonderful presentation.

Ethan Dettmer: I have people. [laughs].

[Inaudible audio]

So that’s sort of the setup of going into the Supreme Court, but it does bring up a few of the themes that we’re dealing with, which was one thing that we talked about a lot, was this notion that President Trump, in statements like that and others ones, talked about using the DACA recipients as sort of bargaining chips for his larger immigration goals and strategies.

And there was a tension that we’ll talk about some more during the course of the presentation between him saying, his administration saying, that there was no legal authority in the presidency to have a program like DACA, but then also saying things like what he said there, which is that he’ll do DACA if the Supreme Court does the right thing. We’re sort of dealing, as many of us are, in this and others areas with a moving target.

So going back to sort of deeper background. Deferred action, I’m going to go through this quickly. Many of your probably know this. Deferred action is a general, sort of something that the executive has used since the Eisenhower administration. Presidential administrations of both parties have because there are too many undocumented people in the country to remove all at once and there aren’t the resources to get rid of them, to remove them from the country, the executive has to make prioritizations among those folks.

So deferred action, and there had been many such programs, including DACA, have said we’re gonna take certain people and tell them that we’re deferring them, and certain benefits flow from that including, very importantly, the notion of work authorization. So if you get deferred action, you can get work authorization and work in the above board economy.

So, DACA is one of the most recent of those programs and here’s President Obama announcing the program.

[Inaudible audio]

So, this Secretary Napolitano, who is the secretary of Department of Homeland Security. She’s also, as you all know, the president currently of the University of California and she’s one of the plaintiffs in one of the companion cases to the one that Dean Chemerinsky and I filed. She was in the Supreme Court last Tuesday watching the arguments and has been an incredible supporter of this cause, obviously, from the beginning and before.

And this is the memo that she drafted and signed back in 2012, which kicked off this program in the first place, and it lays out a lot of the sympathetic issues and the very powerful moral issues that Dean Chemerinsky mentioned at the beginning of our talk about why Dreamers were such important people to protect and why it did not make sense to use immigration resources in order to remove them.

And so in the interest of time, I will very quickly, unless you have anything to add on that, just introduce you to one other important person in this. This is Luis Cortes. He is one of our co-counsels in the case. He is one of a handful of licensed, practicing lawyers in the country who is also a DACA recipient. He’s a good friend of mine. I’ve been working with him for years now, and he’s just an incredibly inspirational and courageous person. He’s going to just briefly mention, he’s talked a lot in the media, but briefly mention why, to him, DACA is so important.

[Inaudible audio]

Erwin Chemerinsky: And I think everyone know the effect of deferred deportation status was for a two-year period. These individuals did not

need to fear deportation. There were also things that would go along with it, like being able to get work permits. So taking away this status would then mean that this group would be in tremendous fear at any time of being subjected to deportation, and lose the other benefits that go along with it. Closely related to DACA was another program, the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans, and if you read the transcript or listen to the oral argument from last Tuesday, there’s discussion explicitly of the ways in which DAPA is similar or different from DACA.

DAPA was about individuals in the United States who are undocumented, but the children, who were citizens, were luckily in the United States. And President Obama created this program to give deferred deportation status to this group of individuals. There’s a tremendous similarity in that the government’s saying

there may be as many as 11 million undocumented individuals in the United States, let’s make wise choices about where to use the power to deport, and it’s not wise to deport the Dreamers because it doesn’t make sense to deport parents who have children who are citizens.

And so this is the description of it, that apply to about 4.3 million people. That’s about 1/3 of those who are thought to be unlawfully present. There was a memo done analyzing its legality before it was adopted, and the slide shows the Department of Homeland Security analyzed this and included that the president is a valid exercise to prosecutorial discretion, could adopt the DAPA program.

The state of Texas filed a lawsuit challenging DACA and the United States District Court and the Northern District of Texas found it conflicted with federal immigration law. It was not a ruling on whether the president had constitutional authority to do, but instead, it was about the conflict between the DAPA executive order and the federal statute. It went to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in a two to one decision. The Fifth Circuit confirmed the District Court that DAPA was a violation of immigration law and affirmed the preliminary injunction.

It went to the Supreme Court, cert. Was granted, it was brief and argued, but it was October Term 2015. On February 13th, 2016, Justice Scalia died, so the Justices announced that they were split four to four. A four-to-four split in the Supreme Court means that the lower court is affirmed by an evenly divided Court. There’s no Supreme Court opinion or judgment entered other than that.

That meant that the Fifth Circuit decision was affirmed, the District Court preliminary injunction stayed in place, and this then becomes a key justification for why President Trump rescinds DACA. And as the slide indicates, after President Trump comes into office, in June of 2017, Texas announced that it’s going to sue the federal government to have DACA enjoined on the basis of the Fifth Circuit’s decision, that it’d been affirmed the Supreme Court by an evenly divided Court with regard to DACA. And the highlighted language that he has:

If by September 5th, Executive Branch agrees to rescind this, the DACA memo, and not to renew or issue any new DACA or Expanded DACA in the future, then the plaintiffs that successfully challenged DAPA and Expanded DACA will dismiss their lawsuit that’s currently pending in the Southern District of Texas. So Texas says to the Trump administration, “If you’ll rescind DACA, we’ll dismiss our lawsuit challenging it. Otherwise, we’re gonna forward.”

Ethan Dettmer: So one of the things that comes out in the course of our litigation, and we’ll talk about it in a little bit more detail as we go along, is that that letter that Dean Chemerinsky was just pointing to was not just out of the blue. Texas didn’t come up with this idea all by themselves to say, “We’re gonna challenge DACA.” We actually uncovered, although we couldn’t really, because of reasons I’ll explain, get into the details of what those communications were.

We knew that Texas, and Attorney General Sessions, and other sorta immigration hardliners within the administration were all talking to each other. So this series of events was very planned out, that the Texas letter was something that had been sort of cleared ahead of time with Sessions and others in the administration. And so that letter came saying, “If you don’t rescind DACA, then we’re gonna threaten it in court.” And then very shortly thereafter, Attorney General Sessions sent, or made public, a letter basically saying DACA was enacted without statutory authority and it was unconstitutional, which is why Dean Chemerinsky points out there was nothing in the Fifth Circuit opinion that Sessions relied upon that said anything about constitutionality. But nevertheless, Attorney General Sessions said that the program was unconstitutional, which is something that we pointed to over and over again in the course of the litigation, that he just got it wrong in this official document.

Nevertheless, he did say that it should be rescinded, and promptly the next day, the then-acting secretary of Homeland Security, Elaine Duke, sent out a memo

saying DACA is rescinded and the reason it’s being rescinded is because, according to the attorney general, it is unlawful. She did not say unconstitutional. We don’t really know exactly why the difference, but it is interesting. I will also say, in case those of you who haven’t heard of it or gotten it, if you’re interested in this topic generally, I strongly recommend you get this book called “Border Wars” that came out about a month ago by a couple of New York Times reporters that tells the story of DACA, rescission, and, more generally, the Trump administration’s policies on immigration, and it’s fantastically reported.

Erwin Chemerinsky: This becomes the key to the litigation in the District Court, the Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court, because if this is the justification given by the government for rescinding DACA, and the question is, is this reason stated in that memo a legitimate reason? And the argument is if not, then it’s an impermissible decision and gotta start all over again.

Ethan Dettmer: Right.

Erwin Chemerinsky: But is the crucial memo that’s much discussed in oral argument and at every stage of the litigation.

Ethan Dettmer: And so, briefly, as you all probably remember, when the rescission happened, and even in the week or so leading up to it, there was a lot of attention around this issue. There’s a lot of talk about what was going to happen and as the reporting and the polling at the time indicated, the U.S. public is, and, frankly, the international public, is strongly in favor of the Dreamers’ rights and them being able to stay.

And so this becomes very relevant to our arguments generally, both in the Supreme Court and before because it is so unpopular of a political move for the administration to get rid of DACA that they are really, in our view, looking for reasons why they can avoid taking responsibility. And so that memo by Elaine Duke really points to just one thing. It doesn’t say it’s a good idea to get rid of DACA. It doesn’t say that this is wise policy. It blames this on a legal determination that we think and we’ve contended throughout this litigation is just wrong. So that becomes a real focal point for this whole case.

This, again, points back to the theme about the president sort of using DACA and the DACA recipients as a bargaining chip for his policies or at least the policies of his hardliners, the hardliners within his administration. You may recall, and this is something that came up over and over again, President Trump had sort

of real conflicted belief, at least according to his public statements and his tweets, about DACA recipients. He said many times early on in his presidency, and even before he was elected, that he believed the DACA recipients should be able to stay, he thinks the Dreamers should be treated with heart, and he made a number of statements like that.

Now that has sort of disappeared more recently, but there was a lot of this type of tweet where’d say things or statements where he’d say things like, “These are great kids and they should be able to stay, but we have to do a deal and we have to have really strong enforcement in the border wall,” and that sorta thing. So it was a real conflict.

So then we filed our case shortly afterward. Dean Chemerinsky and I, along with Mark Rosenbaum of Public Counsel; Larry Tribe; a number of people at my firm; Leah Litman, who’s now at Michigan; and Luis Cortes, who you saw, we had been representing a DACA recipient up in Washington state, a man named Daniel Ramirez, who was one of the first, I think he was the first DACA recipient who’d been arrested and detained under the Trump administration. We’d been representing him for almost a year and when all this happened, we all got together and decided there was something, we really had to do something about the rescission more generally, so we spent a lot of time thinking, and brainstorming, and looking for people who would have, frankly, the courage, the integrity to put themselves out there and put a target on their backs, really.

And so these are our six clients, in this case, who were all at the argument last week and are really amazing people. In the interest of time, I’ll go quickly. Their names are up there, but they are a lawyer, a special ed teacher, a law student at Irvine, a doctor at UCSF, an elementary school teacher in L.A., and a social worker. And they all not only came from really hard beginnings, they all grew up in poverty, and they all not only did these incredible things but have turned all those skills and all that experience back to helping their communities, and all of them work in areas that are underprivileged. I mean, they’re really amazing examples of what Americans should be.

Erwin Chemerinsky: And I think one of the things, and I think this goes to the next slide as well, which I think is the timing, that DACA was rescinded on September 5th, and this lawsuit was filed September 18th. Obviously, to be able to do it in that time, there’d been a lot of thought already given to what happens if President Trump rescinds DACA. It was, this was pointed out, this legal team that had been representing Daniel Ramirez, but it was also thought very important that there’d be a lawsuit brought on behalf of DACA beneficiaries.

We knew that the University of California was gonna sue, gonna serve its interest and the interest of its students, we knew that organizations like the NAACP were gonna file a lawsuit, but we thought it’s so important to put before the Court specific individuals, human beings and their story, and, again, I think this goes all the way through from the beginning of the litigation through last week before the Supreme Court, reminding each level of court that this wasn’t an abstract legal issue. This was about real people and their lives.

I think the next is the complaint. Thinking of the legal theory was difficult. I mean, it’s, again, there was the temptation to wanna make this into

a constitutional issue, to assert constitutional clearance, but it’s a hard constitutional issue because it’s difficult to argue there’s a liberty or property interest here. And I spent many hours arguing this with Mark Rosenbaum, in terms of can we turn this into a constitutional issue, but the primary argument is that under the Administrative Procedures Act, there has to be an articulated legitimate reason for an agency action.

And I think you have a slide there that under the Administrative Procedures Act, the federal statute, courts can set aside agency actions, arbitrate capricious and abusive discretion, or, otherwise, in accordance to the law. That’s the exact language from the Administrative Procedures Act. Then the Supreme Court has said, “Courts must conduct a thorough probing, in-depth review of the agency reasoning, and searching careful inquiry into the factual underpinnings of agency’s decision.” And our argument was the justification that was given for rescinding DACA was that it was illegal, but it wasn’t illegal.

It was a lawful exercise of presidential discretion and that, therefore, since the justification was invalid, the action taken by the president was also invalid. And on the complaint of the right side, if you look, you’ll notice all that was being sought was injunctive and declaratory relief, a declaration that DACA was legal, a declaration that the president’s action was illegal in terms of the Administrative Procedures Act, and an injunction accordingly. No damages were sought as a remedy.

Ethan Dettmer: So we then started a real whirlwind of six months or so, not even six months, of incredibly, just fast-paced litigation activity. We all knew that the rescission had set a six-month sorta wind-down period. So in March of 2018, that was when DACA would be done and there would be no more, that people would be able to sort of end out their terms of DACA. So if they had two years left, they’d be able to finish their two years, but there’d be no new renewals, there’d be no new DACA recipients, and so we knew we had this very short period of time in order to get things done and we really wanted to get as much as information as we could about the sorta thinking behind DACA, the reasoning that the administration had about it.

One of the very important things about an Administrative Procedure Act case is that the agency is required under the law to provide what’s called its administrative record. So that’s the memos, the analyses, the communications, the memos, whatever,that underlie that administrative action. And here we said we want the administrative record for the DACA rescission.

The government provided to us 256 pages. Now in most Administrative Procedure Act cases there, you get boxes, and boxes, and boxes. Well, in the old days you did. Now you get the hard drive, right? But it’s a lot of stuff, and here it was 256 pages, and the vast majority of it was printed from Westlaw. It was the Texas decision and the Fifth Circuit decision in the DAPA case that we described earlier, and they said, “Here it is. This is our reasoning.”

So the first thing we did was we filed a motion to complete the administrative record. Now the case was in front of a very well-respected district judge in San Francisco, Bill Alsup, and he is a very thorough judge. One of the first things he did in this case, and he does this from time to time, was he wanted to have a tutorial. So he had a two hour set aside where nothing was being argued, but we had people come in and just explain immigration law to him, explain the history of deferred action.

We actually had Luis Cortes, who I mentioned earlier, to come in and talk about it because he is an immigration lawyer, he knows his stuff inside and out. So in addition to doing what Judge Alsup wanted, we also though it was a really powerful message to have a DACA recipient who could come in and show his expertise and show his incredible contribution to our legal system. So that happened quickly while Judge Alsup was looking at the motion to complete the administrative record.

And that was granted pretty quickly. He told the government that they had to produce everything and then started I think what we’ll call just an incredible stonewalling effort by the government. They went to the Ninth Circuit and tried to get to the Supreme Court very quickly, both on this issue of our effort to get discovery and the administrative record, and then also, as you’ll see later, try to get to the Supreme Court on the merits in a way that was both unusual and very rare.

So, let’s see. I’m gonna kinda whip through this very quickly. So, I’m sorry, I can’t read very well that very small writing. So at the same time all this motion practice is going on, there’s just an enormous amount of work being done both by my firm, by Public Counsel, by our co-counsel in other places, where we are taking depositions of government actors, we are filing motions, both on the government’s assertion of executive privilege so that they don’t have to produce these documents.

We’re trying to get beyond executive privilege, which, obviously, is a lot in the news right now. We are talking to DACA recipients, to their families, to their employers, to their schools, to their employees, and we are building this record. We had, I think, a total of 108 declarations at the end of the day, very detailed, lengthy sworn statements, of people just talking about how important DACA was to them, to their families, to their communities, to their churches, and being

ready to put that information in front of Judge Alsup in order to get the preliminary injunction motion that we’re filing.

So we had teams of people working on all these different tasks just basically around the clock for several months. At the same time, the government was, as I said, saying, “This is all about executive privilege. “You can’t ask that question. You have all the administrative record there is and there is no more to get.” But as soon as Judge Alsup gave us information, for instance, he ordered the administrative record to be completed, the government immediately went to the Ninth Circuit and filed a mandamus petition, which is a really unusual motion which says essentially this district court is out of control and you have to do something to control them. The Ninth Circuit, we briefed that in the Ninth Circuit. That was argued in the Ninth Circuit, denied that, and then the government very promptly right after that filed a mandamus petition in the Supreme Court on that issue asking that the Supreme Court control Judge Alsup and not let him go forward with this.

Now the way that ended up being ruled on was that the Supreme Court of the United States did issue the mandamus petition. They didn’t say that Judge Alsup was wrong; they said it was premature. And the Supreme Court said before all of this administrative record get produced, the Court should rule on the preliminary motions. If the government wants to file a motion to dismiss the case, that should get ruled on first; Judge Alsup should determine his jurisdiction and that should get ruled on first; and the preliminary injunction motion should get ruled on first. So those all got filed and that was being adjudicated.

Now I just have one little deposition clip here. This is a man named Gene Hamilton, who is a government lawyer. He was at the time in the Department of Homeland Security, and we learned through discovery that he was actually the one who drafted the Duke memorandum, and he actually, a side note, plays a prominent role in the Border Wars book that I mentioned earlier. I give you this clip just because it gives you a real sense of the general approach that the government took during these critical months.

[Inaudible audio]

Erwin Chemerinsky: The District Court grants the preliminary injunction. The District Court Judge Alsup said that the justification that the government gave for rescinding DACA was it was unlawful, but DACA was, in fact, a legitimate exercise of presidential discretion; therefore, there was not an articulated, legitimate reason for rescinding DACA, and the preliminary injunction is granted. And you see the, oh, and you got the President Trump’s response to it. No, that’s okay.

[Inaudible audio]

Ethan Dettmer: So, what happened right away was, and this, again, goes with the theme that we’ve been talking about. The first thing that the government did instead of the usual thing which you do, which is a file a Notice of Appeal and go to the Circuit Court, was that the government filed something called a petition for cert. before judgment, and that is a very unusual procedural mechanism where you basically say this is such an emergency and such a critical situation that we’re not gonna go through the usually appellate route and we’re gonna go straight to the Supreme Court. Of course, you have to ask the Supreme Court to do that. And so what the reason, primary reason the government gave was that this ruling required the government essentially to sanction an ongoing violation of federal law and that they shouldn’t be required to do that. So we were in real time sort of dealing with that petition but also getting ready for the appeal. One of the things that’s interesting here and just as a brief aside, in case like this, you often end up reacting to the news in court, right? So this was a statement that President Trump made in an interview and we’ve got, the reporter’s question is hard to hear so we printed it out there, it’s just an audio interview, and you can hear that this is statements that we were then able to use right away, so.

[Inaudible audio]

President Trump says, “I certainly have the right to put DACA back into place and I might do that,” right? Which you all know by now from our discussion is exactly opposite to what they say, which is that the executive doesn’t have the right to keep DACA in place because it’s unlawful. So we put that right into our opposition to the cert. before judgment that got, you know, the administration can’t even keep their story straight, right? Is DACA unlawful or is it something that the president can do if he doesn’t get his way? And that was something that we thought was really important. We also talked a lot about just how important it is to go through the regular process and that cert. before judgment is usually something that you use in cases of national emergency. So the Supreme Court denied that petition for cert. before judgment and said something to the effect of, “We expect the Ninth Circuit “will deal with this issue in an expeditious way,” which, I’m at four. You want me to talk about Nielsen, or?

Erwin Chemerinsky: You wanna talk about Nielson, the second explanation for why they’re rescinding DACA.

Ethan Dettmer: Yeah, so our case was preceding here in San Francisco in the Ninth Circuit. There were two other large groups of cases that were consolidated on the East Coast. There’s one set of cases in New York, in a federal court in Brooklyn, and another one in a federal court in the District of Columbia. That’s this case brought by the NAACP, by Princeton University, by Microsoft Corporation, and by a number of individuals. And in that case, the judge approached it slightly differently. Same ultimate result, but slightly differently than Judge Alsup. Just Bates in the District of Columbia, instead of entering an injunction, he vacated the rescission, which is something you can do under the Administrative Procedure Act. Just say that action is ineffective. And he did that and then he said, “But I’m going to give the agency a chance “to kind of do it over again, “and if they wanna give, “If they wanna do a new rescission “and explain the real reasons behind it, “then that’s something they can do.” The government decided not to exactly take him up on that. They instead said, “We’re going to leave the original rescission in place,” and this is then, so Kirstjen Nielsen was now the secretary of Homeland Security, “We’re gonna leave the rescission in place, “but sort of give some new reasons for it.” And the reason we’re giving you this aside is because this becomes very important as the case goes forward, and the question, and this is something that Dean Chemerinsky sort of alluded to, was do you have to talk about just the reasons that are given for the initial action or can the agency then come along later and sort of, I don’t know, bolster the record later along? And that becomes an issue in the Supreme Court.

Erwin Chemerinsky: It’s worth noting that Judge Bates is by any account a conservative judge, a Republican appointee, to the extent that if someone wanted to focus on the ideology and pull like a party the president appointed, Judge Bates coming to the same conclusion, I think, was quite powerful. The Nielsen memo gives four reasons for rescinding DACA, but they’re quite similar to what it was before, that DACA was illegal, or they had substantial doubts about the legality of DACA based on the DAPA ruling and the like. Probably it’s worth, especially certain times you talk about the Ninth Circuit opinion and the census case. So long as, go ahead, please.

Ethan Dettmer: I’ll just push it forward to that.

Erwin Chemerinksy: The Ninth Circuit panel was Kim Wardlaw, Jacqueline Nguyen, and John Owens. Ideologically, I think of Wardlaw as the most liberal of those three. I’ve argued several times in front of both Judge Nguyen and Judge Owens, and I think of them as moderate liberals, but certainly not among the most liberals on the Court. And the Ninth Circuit affirms the District Court. Judge Wardlaw writes the opinion, Judge Owen concurs in the judgment on slightly different grounds, but the basic point that just by Judge Wardlaw is that DACA was legal and that, therefore, the justification that was given for rescinding DACA is impermissible. There were actually two questions before the Ninth Circuit, and they’re the same two questions that the Supreme Court faced last week. One is, is the decision of the president to rescind DACA judicially reviewable? The position of the government before the Ninth Circuit and before the Supreme Court was a president’s exercise of prosecutorial discretion is unreviewable, and that, therefore, there’s no basis for the Court being able to review at all. And Judge Wardlaw in very strong language says that it is subject to judicial review, and, in fact, I don’t know, is the quote right?

“Marbury versus Madison” is citing, for those of you who’ll have me for Common Law next semester, so I start the semester with Marbury versus Madison. It really does matter. And the merits having decided that it’s reviewable, she says, as I mentioned, that President Obama had the legal authority to adopt DACA, thus the justification that was given for its rescission was invalid. Now, I don’t know if there’s something about the Ninth Circuit ’cause I wanted to say a word about the census case that came down after this. After this, on June 27th, the Supreme Court decides Department of Homeland Security versus New York, and that involves whether or not it was permissible for the Congress Department to get a question about citizenship on the 2020 Census. The Supreme Court, in a five to four decision, finds that it was impermissible to add this question on citizenship because there wasn’t a legitimate reason given to the administrative process.

Now what happened here was, according to Chief Justice Roberts, the Congress Department asked the Justice Department, “Would it help you if we asked a question about citizenship on the census?” And the Justice Department said, “No, we don’t need it.” The Congress Department then went to the Department of Homeland Security and said, “Would it help you if we asked a question about it?” And the Department of Homeland Security said, “We don’t need it.” Then the secretary of commerce, Wilbur Ross, asked the then attorney general, Jeff Sessions, “Wouldn’t it really help you if we asked a question about citizenship?” And Jeff Sessions said, “Yes, it would help us enforce the Voting Rights Act.” But there was no evidence whatsoever that it would help enforce the Voting Rights Act. Chief Justice Roberts said, “This was just the secretary, or the attorney general, doing a favor for the secretary of Congress, and that doesn’t count as a legitimate reason for purposes of the Administrative Procedures Act.”

Now four justices, Breyer writing, joined by Ginsburg, so then Kagan said, “We should just invalidate the decision of the Department of Congress.” But Chief Justice Roberts said, “No” — that the Court should give the Department of Congress another chance to come up with a legitimate reason. I confess, when I read this on Thursday morning, June 27th, I was perplexed by it. The Court said, “There has to be a legitimate reason for the action. It can’t be a pretext. The Department of Congress, they’ll come up with another reason.”

Well, if you remember what then played out was the Justice Department told the federal judges on Tuesday, July 2nd, they weren’t gonna seek a question about citizenship. The Justice Department issued a press release it wasn’t gonna seek a question about citizenship on the census. That night, President Trump tweeted, “Fake news, we are gonna seek a question on citizenship.” They couldn’t figure out a way to do so. On Monday, July 8th, the government announced it wasn’t gonna seek a question on citizenship on the census. But the reason it’s relevant here is the core argument that’s being made is that the justification given rescinding DACA was illegitimate. Likewise, the Supreme Court says the Department of Congress versus New York, the reason that was given there was not legitimate and that was the basis for invaliding the action.

Ethan Dettmer: So the census case was something that came out right about the same time as the cert. grant in our case. I think it was the day after, if I remember right.

Erwin Chemerinsky: And if I can just mention, the cert. petition was pending before the Supreme Court for months, and the Supreme Court kept relisting it, taking no action on it. Then it took it off of the conference calendar all together, and there were many conferences where it wasn’t listed at all and no one could figure out what happened to it, until, finally, in June of 2019 the Court then grants it at the end of the term.

Ethan Dettmer: So we all were, you know, thrilled every time that it was passed by, and then when it was taken off the conference list, that was great. When cert. was granted, we, obviously, were all not happy about that, but we did have this opinion in the census case at the same time that gave us, that really sort of reinforced a lot of our theory of our case about what our case was about. So then we engaged in a real sort of, another whirlwind of getting ready for the arguments. So the cert. was granted in all three of those groups of cases. There’s actually nine cases all together in three groups. I think there’s something like 45 plaintiffs in all these cases, so there’s a lot of discussion about who was going to present the argument, and the argument really was this APA issue that we’ve been talking about.

Now one of the things that we thought, this is some headlines from shortly before the argument, one of the things that we thought was really important, we knew we had to reach some of the more conservative members of the Court who traditionally may not have had seen this case our way or maybe in the DAPA case voted the way that we didn’t like. Now when you’re getting ready for a Supreme Court case, as many veterans, Supreme Court advocates say, you don’t take any vote for granted, and you don’t count any vote out, and you do everything you can to get to five votes. So one of the things we were really hoping to do is to have Ted Olson, who’s one of the senior partners in my firm, he was the solicitor general under George W. Bush, and was private lawyer to President Reagan, and head of the OLC back in the ’80s, and is known as somebody who’s a real expert on and proponent of executive authority, which, obviously, is something that was very important in our case. We wanted somebody to say, “The executive, of course, has the power “to do a deferred action program like DACA,” and we thought that Ted would be great advocate for that in addition to the fact that he’s just a very frequent advocate at the Supreme Court and knows it well.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Maybe I should add here, in the Supreme Court, it’s generally one lawyer per side. It’s truly extraordinary, as here, to have two lawyer on a side. And when there are multiple cases that are consolidated, if the lawyers can’t agree as who’ll argue, the Court will flip a coin to decide among them. Now lawyers who are involved, generally, would want the opportunity to argue, and I cannot tell you, though I was not privy to all the discussions, I know about a lot of them, that it was a friendly discussion at all moments and that it was consensus as to who should argue, ’cause certainly some of the other lawyers who argued in some of the other cases. Remember, these are several cases that have consolidated. We’re all jockeying for who should argue, but I certainly was one who thought that Ted Olson was the logical choice because he was the solicitor general of the Republican administration. He did personally know the conservative justices on the Court, and it would, I think, send the best possible message in that regard, but it sure wasn’t an easy conclusion for the people to come to.

Ethan Dettmer: There were a lot of discussions. Dean Chemerinsky is right. But one of the other messages that we wanted to get across was this, I think, really important message that, I don’t know if we’ve conveyed it strongly enough, but I think Ted’s involvement really helped with this, was that this should not be a political issue, right? This is an issue of the rule of law and of the government being accountable for its decisions, and giving accurate reasons for what it’s doing. We wanted to sort of take the Republican and Democrat issue out of this as much as possible, and one of the things we’re very adamant about was having Luis, as a DACA recipient, be the person who sat right next to Ted at counsel table in the Supreme Court during the argument so that he’s, if you’ve never been to the Supreme Court, counsel table is about five feet away from the justices. You’re really right there, staring right into their eyes, and having somebody who is himself a lawyer and himself going to lose his law license, at least conceivably if this goes the wrong way, is a powerful message and is something that we thought was really important to humanize the whole thing, as we were talking about at the beginning. And we do wanna leave some time for questions. So we have a few clips here of the argument. Okay, and there are no cameras in the Supreme Court, just so know, so you get it drawn.

[Inaudible audio]

Erwin Chemerinsky: I think one of the things that Ted Olson did, which was exactly right, was begin his argument by talking about the people who were involved and the human consequences of this. I was not in the Court. The lawyers who wanted to be there, other than the constable, had to be there at two in the morning on Monday night, Tuesday morning. I was in D.C. because I was arguing a case on Wednesday morning in the Court. I decided it wasn’t the best use of my time to spend the night before outside in the cold, but I had a chance to read the transcript of the argument and I think what Ted Olson did from the very beginning was really try to remind the judges of the people involved, and some of the justices were very receptive, I think Justice Sotomayor in particular, really wanted to remind the colleagues.

Some seemed quite indifferent to it. I think that the dilemma that I mentioned at the beginning was present throughout the oral argument. If, on the one hand, DACA is illegal, then President Trump is justified. If DACA is lawful, it’s ’cause the president has broad, inherent powers with regard to immigration, and if the the president has broad, inherent powers regarding immigration, why can’t one president rescind what another president has done? And I think that really is center. Lots of discussion at the oral argument about the reviewability question. When can the Court review a presidential decision to prosecute or not prosecute, deport or not deport? As well as the merits question. And it wouldn’t surprise me that this case could come out on the reviewability question without ever reaching the merits question.

All right, should we take five minutes of questions?

Ethan Dettmer: Yeah.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Questions that you have about, especially just the litigation strategy along the way. Please.

Audience 1: Hi, I have a question. So what are the things that’s been most concerning for promoting DACA and, say, be it testing, and what’s gonna happen if say that, worst case scenario, the case does not count favorably, has there been anything in the arguments or the in courts that suggest that the Trump administration plans to use the information that people contributed as part of the DACA application process?

Ethan Dettmer: That’s a great question. So it was that exact issue was part of the litigation early on, and one of the things that, in our case and I think all the cases challenging this, there we really did bring some of the constitutional arguments that Dean Chemerinsky was mentioning earlier about, that are challenging in sort of the broader sense but with respect to information that people, and just for those of you that don’t know, in order to get DACA, you have to give your fingerprints, you have to give your address, you have to have a background check, all sorts of really personal and private information. So we brought claims and the courts have all upheld them, saying that information cannot be shared. Now I do think just knowing how the law works and how politics works, that’s something that we’re gonna have to be vigilant about in the future, and make sure that those get followed. I don’t know if you have more on that, but.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Other questions, please.

Audience 2: Is there sense of whether work authorizations would be completely invalidated or whether they’d be allowed to expire should the .

Erwin Chemerinsky: Yeah, I mean, that would ultimately be up to the Trump administration. There certainly is gonna be litigation of reliance and whether or not the work authorization might create some kind of liberty or property interest, but, ultimately, I don’t think anyone could answer that question at this time ’cause the government hasn’t taken a position.

Ethan Dettmer: Yeah, I think that’s right and I think it’s not an easy question, honestly, to answer. I do think the good news is that their two-year tail on what people have as far as work authorization now, I mean, as far as it doesn’t go away until their DACA is gone, and that will last two years after it was granted, so hopefully that will get people to a new, some kind of new status.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Other questions? Please.

Audience 3: So what happens if the Court rules in your favor and essentially does what they did in the census case? So they say, “Look, you come up with a reason you can rescind DACA.” The government isn’t on a timer like they were in the census case, and that’s kind of why it worked out in our favor. Is the goal here just to push this along until we can get into another administration where this isn’t a threat?

Erwin Chemerinsky: My answer is yes. My hope is that no matter what the Court does, that they’re gonna wait until the end of June to do it, and if they reverse the Ninth Circuit, that some of the liberal justices will take a very long time writing their dissents to get us to the end of June. That if they should affirm the Ninth Circuit, better towards the end of June anyway. That should they reverse the Ninth Circuit, my hope would be that Congress might act very quickly in a focused way with regard to DACA itself, since DACA is overwhelming, support the polls, it’s an election year. I’m less optimistic, but if not, I would hope that President Trump, if he wins in the Court, might still reinitiate DACA. But if none of that happens and DACA expires, then you get to what the counts are gonna be and if the Supreme Court affirms the Ninth Circuit, the bottom lines would give the Trump administration another chance to repeal DACA but with legitimate reasons, and hopefully that would stretch out till the end of the administration.

Ethan Dettmer: Yeah, I agree with that. I do think that, actually, there is, if the Court does follow our theory and holds them to having to give an honest policy reason, in other words, they have to say, “We think DACA’s a bad idea,” or, “We recognize all these costs of rescinding it and we wanna get rid of it anyway.” I actually do think that’s a harder thing to do. I’m not saying they wouldn’t do it, but I think that’s harder to do when they have to be forthright about the reasoning and be held accountable for it.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Thank you all so much for coming. Ethan, coming here, coming and doing the work.

[Audience applauds]