Student Chaka Tellem on finding his voice, embracing his African roots

First-year Tellem, who spent his early childhood in The Gambia, talks about the pressure to assimilate to American culture, learning to love both his countries and how he finds common ground through healthy debates

February 26, 2020

First-year student Chaka Tellem plans on majoring in political economy and business administration with a minor in race and law. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

“I was born in Dallas, Texas, in 2001. When I was 18 months old, my parents agreed to send me to my mother’s native country, The Gambia in West Africa, so that I would gain exposure to my African roots and culture. For the next few years, I lived with my maternal grandmother and family members.

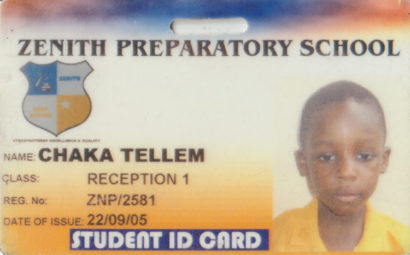

Tellem started school at age 4 when he lived in The Gambia. For the few years he was there, he learned to speak French, Wolof, Krio and English. (Photo courtesy of Chaka Tellem)

My grandmother was the head educator in The Gambia — she was the principal of several schools and was in charge of administering the college entrance exam. She always stressed the importance and power of education. She made sure that I started my formal education pretty early — at age 4. It’s probably because of my early education that I learned to speak French, Wolof, Krio and English fluently while I lived with her.

When I was 6, I came back to the United States and moved in with my mother in Los Angeles, California. About a year later, I moved to Dallas to live with my father. He was part of the Green Party and worked in local politics. We would have conversations about politics and the importance of understanding the political climate and different ideologies. He wanted me to derive my own political identity based on my own logic.

From left: Tellem’s stepmother Preeti, brothers Pratik and Sujash, his father Sundiata and Tellem at age 13 during the hoidays in Dallas, Texas. (Photo courtesy of Chaka Tellem)

One thing that he taught me is to question everything. He always said, ‘If you don’t believe something, fact-check it.’ I always try to question my sources and thought patterns — why I think the way I do.

I started to get bullied a lot in middle school. At that time, I still had my British African accent — my peers would laugh at the proper way that I spoke. My paternal grandmother — who I spent a lot of time with — said that one time I was on her bed and I told her, ‘I’m never going to speak French, Wolof or Krio ever again. And I’m going to lose my accent.’ Within a matter of months, she said, it was gone.

The weird thing was that a lot of the teasing came from my black peers, which I always thought was strange because that was the group I felt that I identified with most. So, in my aspirations to assimilate, I wanted to be more ‘black.’ I took up basketball because being, you know, a skinny, tall, black kid, if you want to assimilate, society tells you that if you want to fit in, you should play basketball. I felt pressured to hide that I was smart and my passion for learning.

Tellem (back right) with his maternal grandmother, Comfort (far right), his mother, Julia (second from right), and his aunts and uncle at a family reunion in North Carolina in 2018. (Photo courtesy of Chaka Tellem)

When my dad found out I felt like this, he gave me a binder of materials about my African heritage. He told me it wasn’t something I should be ashamed of — that I should embrace both sides of my family. He also shared with me the children’s books he had written and published about my fictional adventures in Africa. One is called Chaka goes to Zambia. I think there are seven in the series now.

That’s when things in my life shifted. I started identifying as African American, in the sense that my mom was African and my dad was American — that I was born in America, but I was raised with African culture and ideals, to an extent. And I realized it was okay to be smart, and I started going to the library to learn about subjects I found fascinating, like history, geography and zoology.

Tellem, with his maternal grandmother, Comfort, was named valedictorian of his high school graduating class. (Photo courtesy of Chaka Tellem)

The summer after my sophomore year, I moved back to California to live with my mother in the San Fernando Valley. Initially, I was reluctant. I had everything set in Dallas — I was on the varsity basketball team, I knew all the AP classes I was going to take, I had been nominated to serve on the student body as junior director. But the decision was made, so I started my junior year in California at James Monroe High School.

On my first day of school, my English teacher encouraged me to join the speech and debate team. It was the best decision I have made, because I found my passion for public speaking. I also joined the black student union and later became its president. Finding my voice was a revolutionary thing for me.

I continued to play on the varsity basketball team. In Texas, all of our games were after school, so we never missed class. But when I started playing basketball in California, I noticed that games always started during lunch, so we would miss half our classes.

In high school, after Tellem saw a lot of his student-athlete peers struggling to maintain their grades, he started VASA — Viking Athletes Soaring Academically. (Photo courtesy of Chaka Tellem)

I saw a lot of my peers struggling to maintain their grades, and after discussing the issue with my family in California, I decided to start a club called VASA — Viking Athletes Soaring Academically — a support group that helped student-athletes have access to tutoring services. Students could get help with preparing to take the SATs and ACTs, and with college applications. It ended up benefitting not only student-athletes, but other students at the school who sought VASA’s help.

After I was accepted to Berkeley, I visited the campus during senior weekend as part of the Black Recruitment and Retention Center. I spent two days living on the Afro floor in Unit 1 and became immersed in the culture there. At that point, I knew I wanted to come to Berkeley and live on the Afro floor.

At Berkeley, I’ve had the opportunity to speak with other people who have experienced some of the things that I’ve experienced. At Berkeley, living with my peers on the Afro floor, we can talk about social justice issues and see how we can collaborate on alleviating some of the issues that are happening in the U.S. and work on changing the political, social and economic culture.

Tellem lives on the Afro floor in Unit 1 with first-year student Kai Koerber. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

I plan on majoring in political economy and business administration with a minor in race and law. After undergrad, I’d like to go to law school and become a practicing attorney working in social justice to help alleviate discriminatory practices. If I can do more as a public servant, then I might dive into federal or municipal politics.

Nowadays, I try my best to have healthy debates or conversations with people who might not agree with me on certain topics — not to convince them that they’re wrong, but to learn their viewpoint. Because how you grow up influences how you think, I believe if you show a person that you’re willing to learn and not just attack them, they will be more likely to listen to you, as well.

I’ve noticed that, oftentimes, when people debate, although their stances seem to contradict one another, their core principles are often the same. Communication, methodology and personal experience are often what cause the apparent differences to arise. Understanding that, I believe, is integral to finding a compromise.”

From left: First-year students Koerber, Tijaan Issah Henderson, Tellem and Mohammed Zareef Mustafa sit in front of Doe Library. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)