In Afghanistan, Maryam Karimi dreamt of school. Now, she’s a role model for girls.

The first-year student shares her journey, from feeling like school was out of reach as a child to being accepted at UC Berkeley and her plan to build schools for girls in her home country

March 10, 2020

First-year student Maryam Karimi plans on majoring in economics and Persian with a minor in global studies. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

“I grew up with my five brothers and sisters in my father’s home village, which is in the countryside of Kabul, Afghanistan. I have beautiful memories from my childhood, living in the countryside, helping my dad work in the vineyards — we grew grapes, walnuts and berries.

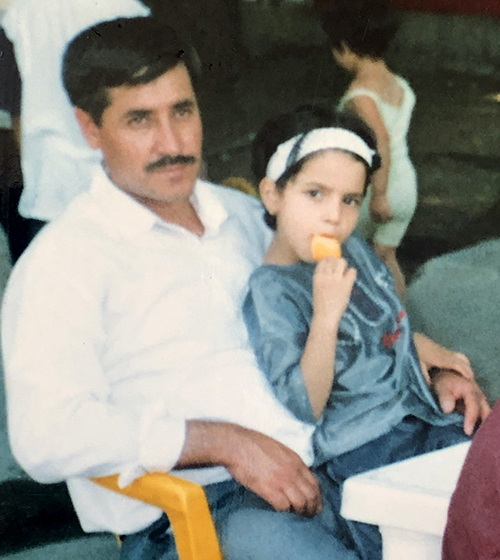

Maryam sits with her father, Muhammad, a few years before he was injured by a bomb planted near a government building. (Photo courtesy of Maryam Karimi)

But as much as I enjoyed all of that, there was always something missing from my life: an education.

My mother, she is from the times when Afghanistan was different. There was no war. She went to school, her siblings went to school. By the time I was born in September 2001, most of the girls’ schools had been burned down by the Taliban, who had taken control of most of the country beginning in the mid-1990s. In December, when I was 3 months old, the Taliban was overthrown after the American-led invasion following the Sept. 11 attacks. Girls could go to school again, but the educational infrastructure had been destroyed.

My parents weren’t like everyone else who accepted what was going on, who thought this was the way of life. My mom ran a school at our house, where she taught girls ages 8 to 14 how to read and write. Her school was funded by NGOs, like Save the Children. My mom had to convince a lot of parents to let their daughters attend. Sometimes they would be persuaded to let their daughters come by the things she would give the students, like backpacks and toothbrushes.

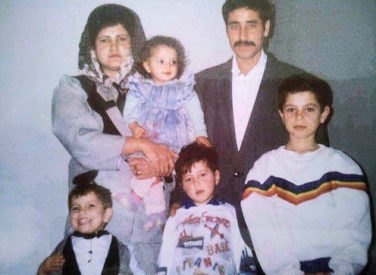

From left: Maryam’s sister, Amira; her mother, Najia; Maryam; her brother, Amir; her father, Muhammad; and her brother, Samim (Photo courtesy of Maryam Karimi)

My sister was high school-age at the time, and my mom would let her go every day to the city where there was a school for girls. She was the only girl who would go out of our village to the city. There were so many times when people, even people close to us, would tell my dad, ‘I don’t think it’s good that you’re sending your daughter to school. You have to be like everyone else.’ But my mom didn’t give up. She said, ‘In many years to come, maybe things will change and your daughters will go to school. But if mine don’t get an education now, they will be left illiterate.’

When I was 7, my dad happened to pass by a government building, and there was a bomb planted on a street vendor cart. It was meant to destroy the building, but my dad was severely injured — he lost his hearing, his sight in one eye and the use of both of his legs. Doctors amputated one of his legs, but my mom begged them to let him keep his other leg in case there were better medical treatments later. Now, when I look at his leg, I remember my childhood and feel terrified.

After Maryam and her family moved from their village to the city, the 7-year-old began taking English classes at a school run by a relief organization. This is the photo on her ID card. (Photo courtesy of Maryam Karimi)

After that, my dad was 100% disabled and couldn’t work anymore, and my mom had to take everything into her own hands. She started working for government organizations, like UNICEF, in Kabul. We moved away from the village to the city because everyone was judging her for working and going outside not wearing a burka anymore. Not only was she risking her reputation, but she was risking getting hurt by people who disapproved or by terrorists.

In the city, I went to school run by a relief organization for one hour a day to learn English. Most of the time, we would be on lockdown until dark because of a nearby explosion or armed conflict between the government and terrorists. Teachers had to escort us in small cars and bring us home because they didn’t want us to get hurt.

After one of my mom’s colleagues was shot and killed in Kandahar doing field research and another close friend and colleague was shot in a mall in Kabul, my mom thought, ‘If I’m alive, I can do more.’ So, she applied for asylum in the United States. Eventually, my family moved to Fremont, California.

I started school at Walter Junior High when I was 12. At first, I felt like I couldn’t fit in with the other kids because I was too mature. I didn’t understand why they would disrespect the teacher. I come from a culture where when you see a teacher, you just look down, you don’t even look in their eyes. At the same time, growing up under so much control, I felt like my ideas weren’t heard, that I didn’t have the freedom to be creative or express my emotions the way we have here.

In high school, I joined a nonprofit college prep program called AVID and we took a field trip to UC Berkeley. It was my first-ever field trip. We came to the campus and I just felt that it was the place for me. People walking by me looked so passionate and they looked so different from each other. I thought, ‘One day, I will come back here and I will find myself and my true potential.’

“Growing up, there weren’t a lot of women role models, besides my mom, whom I could relate to or look up to,” says Maryam. “So, I decided to become one.” (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

As a teenager, I got involved with a coalition of Afghan artists in Fremont, where I started to read Persian poetry. Last summer, I was chosen to speak for an AVID summit in San Diego, where I recited two verses of poetry by Rumi. I read it in Persian and then translated it to English, then posted it on Instagram and it kind of went viral.

Today, I have a lot of girls who support me and look up to me — girls here and also girls in Afghanistan. I just really try to motivate them. I share my journey of college with them and talk about how, when I was 10 or 11 years old, I never thought I would go to college. Even though I’m far from Afghanistan, I still love my country. I try to tell them, ‘I’m just like you. I have the same feelings. If I can do something, you can do it as well.’

I started an organization called Educate a Child for Change. I feel that the way to transform a society is by educating the children. I want to use every opportunity that I have to support education in Afghanistan. I’m planning to build a library in my family’s house in Kabul and eventually, I want to build schools for girls.

I get messages from girls telling me how much I inspire them. That has been my goal and wish that I’ve always had and now it’s coming true. Growing up, there weren’t a lot of women role models, besides my mom, whom I could relate to or look up to. So, I decided to become one.”