Coronavirus forces hands-on learning to go online and hands-off

With only a few days notice, graduate student instructors scrambled to put lab courses online

March 23, 2020

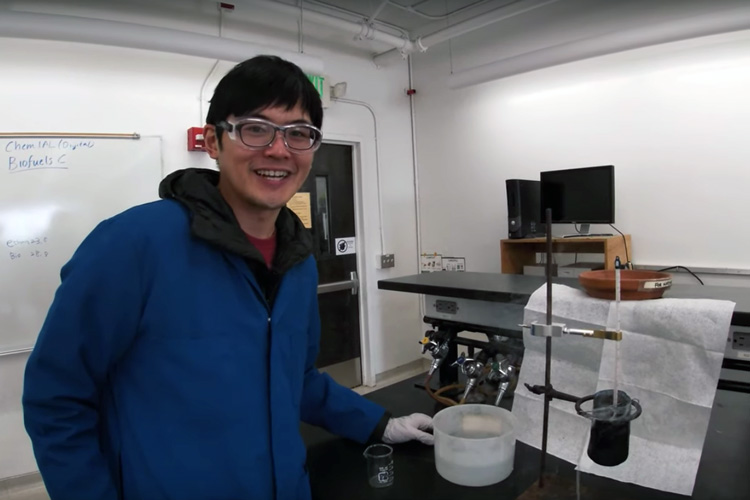

Andy Lin (top right) interacting with GSI colleagues as he prepares for online ‘virtual’ office hours using Zoom. (UC Berkeley image by Andy Lin)

When the growing coronavirus pandemic compelled campus officials to halt all lectures and most in-person classes as of March 10, most faculty and lecturers were caught off guard. Few had experience teaching online courses. Most had to scramble to learn how to deliver lectures via Zoom or through b-Courses or other teleconferencing services and to pick up tricks from colleagues about how to be remotely engaging.

Hands-on classes, such as labs, physical education and performance classes, seem spared.

But then, on Friday, March 13, the campus canceled all in-person classes too, throwing a wrench into the interactive training critical in many fields. How do you teach dance or theater, how to craft a vase on a potter’s wheel, run a gel, titrate an acid or use a micropipette without in-class practice and coaching?

Within science departments on campus, graduate students leaped into the breach. With only a few days’ advance warning that labs would be moved online, most of the nearly 110 graduate student instructors — GSIs — in the Department of Chemistry labored in shifts to photograph and videotape experiments for nine separate lab courses, ranging from introductory freshman chemistry to advanced synthesis. They then packaged the multimedia into PowerPoint presentations that students — nearly 2,500 in all — could download, click through and get the data needed to write up and submit a lab report.

“We want to definitely give credit to the GSIs. They really stepped up and used all of their smarts and creativity,” said Laura Fredriksen, supervisor of the instructional support facility in the department. “They’re here to learn chemistry and get a Ph.D. in chemistry, not go to film school. But they did this, and they did it really well.”

Chung-Kuan (Andy) Lin, a second-year graduate student, was one of those GSIs. He grabbed the GoPro he usually dons when skiing and helped create within a few days materials that normally would be carefully prepared and tested over years.

“I felt it’s like entering a territory that none of us has ever explored before,” he wrote in an email. “We wanted to craft a learning experience that allows students to absorb at their own pace, which is expected to be much longer while they are learning at home, and in the meantime, we had to identify objectives and give very clear instructions. The most difficult part is probably seeking feedback immediately; otherwise, this experience would only be a single channel.”

Streaming lectures; virtual office hours

Michael Zuerch, an assistant professor of chemistry, also had to move quickly to adapt his upper-division physical chemistry lab lectures to online learning. Having arrived on campus only seven months ago, he said he’s someone who “likes to walk around the classroom and engage; approach a student and say, ‘What do you think about this?’ or ask if there are any questions.”

At a time of enforced social distancing, Zoom allows chemistry professor Michael Zuerch to talk to students in front of a serene natural background while hiding a cluttered home office. (UC Berkeley photo by Michael Zuerch)

While he learned how to livestream his weekly lecture, his three GSIs worked night and day to put all the lab experiments online.

“It was a wonderful job that the GSIs did to get to the point where we are today: The students, in my view, can 100% complete this course and get their credits this way,” Zuerch said. All six sessions are online as PowerPoint presentations, with GSIs standing by via Zoom for “virtual” office hours. Those students who have gone home, some outside the United States, can file their lab reports as PDFs or even opt for a Zoom oral report.

“I think, in general, the faculty have been stressed out,” said Anne Baranger, director of undergraduate chemistry and a teaching professor of chemistry. “This has been a very alarming transition to make so quickly. They don’t necessarily have the equipment they’d like, and they haven’t been able to try it out. Even in a lecture class, people like to practice in advance. People are now trying different things out and sharing ideas on the fly.”

Zuerch now sits in his home and streams his lecture via Zoom, though, thus far, with little feedback: something he truly regrets.

“What’s missing is the active interaction,” he said. “I immediately felt it was taking away something, but it is the best we can do right now. It’s not just us instructors learning about this technology, it’s also the students who have to get used to using it actively. I assume it will get better as we use it.”

“The point (with labs) is the hands-on experience, which, unfortunately, will be missed now,” Baranger said.

Students and instructors both adapt

Michelle Douskey, a lecturer in the college who is the instructor for Chem1B and Chem1AL, the introductory chemistry and lab courses, was more prepared than most. Several years ago, she took an active learning course offered statewide by the Lawrence Hall of Science. But the techniques she learned aren’t always possible with Zoom, or compatible with working from home. She’s no longer streaming her Chem 1AL lectures to 600 students, but scrambling to make videos she can put online, so she can host viewing parties as her students watch and discuss the material.

Lecturer Michelle Douskey now interacts with students via Zoom as she teaches an online chemistry lab. (UC Berkeley image by Michelle Douskey)

She is also concerned about the difficulties some students are having with distance learning, in particular, those who have gone home to sometimes chaotic environments and can’t find a quiet study environment. Places where students typically go to study, such as public libraries and coffee shops, are now closed because of the pandemic. One student responded to her anonymous survey about online issues by writing:

Things are difficult for me personally at home. It is difficult to find a space where I can study effectively, and the rest of my family does not make this easier. On top of this, my grandmother passed away today. I also have obligations to help out with the family business. I am more stressed about school now that I am home, and I am finding it very difficult to even understand the purpose of the lab.

“It’s heart-wrenching,” Douskey said.

As she seeks advice from colleagues about how to help students like these, she tries to balance her own home teaching environment.

“I kinda went underwater a bit myself,” Douskey admitted, stressing out after being given two-days’ notice that all classes were going online. She worked 12- to 15-hour days to prepare.

“I just wrote to my students that I’m pressing pause,” she said. “My body was giving out, I had to take a break. I said, I am extending the due date because I need an extra few days. They were OK with that.”

Lots of hurdles

Another large lab course, Bio1AL, met in person as late as March 13, learning, ironically, about PCR and how to prepare samples for DNA sequencing — all techniques now being used to diagnose COVID-19 infections. The campus closure has left lab manager Erol Kepkep considering 20th century alternatives to in-person learning, such as mailing each of the class’s 600 students a lab kit to complete at home. That won’t work for a scheduled April rat dissection, however, so lab instructors may have to create video that students watch online. The same is true for a subsequent lab where students measure their bodies’ responses to exercise. And video may not even be an option, since Kepkep and the instructors can’t step on campus without authorizations.

“The students are just asking, ‘How are we going to do this? What assignments do we need to do?’ It’s pretty confusing, especially since we have some students in another country now, with maybe an 8- to 12-hour time difference,” Kepkep said. “Trying to figure out this situation is complicated, and no solution will please everyone.”

Undergraduates aren’t the only ones maneuvering around challenges with online learning. Instructors are encountering difficulties, too. One person teaching Bio1AL has already returned home to Texas, while another doesn’t have equipment or a home suitable for effective use of Zoom.

“There are a lot of hurdles,” Kepkep said. “And that still does not address how to have exams, which have typically been in-class multiple choice. It’s going to be a challenge to fairly test what students have learned, while coordinating with everyone in different time zones and (with) variable internet connectivity.”

Kepkep has also had to teach instructors unfamiliar with Zoom, virtual whiteboards and other online course tools.

“We’re still learning and trying to figure it out,” he said.

Douskey noted that the campus recognizes the difficulties of rapidly moving online and has encouraged instructors to lower expectations.

“It is unreasonable to expect that students can learn the same amount of stuff in this format when we are all just flying by the seat of our pants,” she said. “They could learn in a good online environment, for sure, but I think very few of us are offering that. We are just scrambling to get something together. That is where the frustration lies.”

Most faculty, GSIs and lab managers are optimistic that going fully online will work out well enough, once people get the hang of it. Everyone is taking notes, learning from one another via list serves such as teachnet and trying to get student input on what works and what doesn’t.

Few, however, seem to want online labs or even lectures to be the new norm.

Nevertheless, Zuerch noted, the material everyone is now preparing can, in the future, supplement courses to make them more accessible for students with disabilities. And the next time a wildfire in California closes down the campus, the campus will be prepared.