Berkeley Talks transcript: Art Cullen on journalism and politics in the Corn Belt

April 24, 2020

[Music: “Silver Lanyard” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Podcast intro: This is Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. You can subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen. Also, check out our other podcast, Fiat Vox, about the people and research at Berkeley. You can find all of our podcast episodes with transcripts and photos at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

Ed Wasserman: Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. I’m Ed Wasserman, Dean of the Graduate School of Journalism. Let me start by asking you to turn off your phones. Turn off means when it says, “On,” it means off. This is one of the new wrinkles in the Apple’s training us to use their technology better. It’s silence mode off means that the ringer is on. We don’t want that. Okay.

As a Dean of communications school, this kind of mastery of advanced technology is part of the job. Thank you very much. Welcome to a stellar evening. This event is sponsored by the UC Berkeley 11th-Hour Food and Farming Fellowships. That is a program that Michael Pollan and Malia Wollan, the director of the program put together in 2013 with the support of The 11th-Hour Project, which is a philanthropic initiative headed by Wendy Schmidt. Also, a distinguished graduate of the journalism school, as is Malia Wollan.

A shout out to 11th-Hour Foundation and Sarah Bell, a close associate of Wendy who’s with us tonight, I hope. She’s on her way. Be nice to her when you see her because the 11th-Hour has been very good to us and to the Food and Farming Fellowships and to the school of journalism. This fellowship provides funding, training and editorial support for print and audio journalists who are reporting on stories related to food and agriculture. Nearly 70 fellows have gone through the program since 2013.

Their stories have reached millions of readers and viewers through national outlets, including the New York Times Magazine, NPR, Rolling Stone, Mother Jones, 99% Invisible and many more. Our host this evening will be Michael Pollan. Michael holds the Knight Chair in Science Journalism at the Graduate School of Journalism. Michael, I need hardly tell you, is one of the world’s most admired and influential writers of nonfiction for the past 30 some odd years.

His books and articles helps spark a worldwide revolution in our understanding of food and its future. Most recently, his newest book, How to Change Your Mind, is helping transform the way we look at psychedelics and their use. One can only wonder what next complex and nettlesome question Michael is going to tackle. My own, I am curious actually about death. I would like him to do a story on death, myth and reality. Do a book on that.

It may not have motion picture potential, but I’ll certainly read it. Michael will be playing a supporting role tonight to our guest of honor. He is the editor, co-founder and co-owner of a newspaper and I will bet that none of you have read and few of you have heard of which is the Storm Lake Times. Twice a week, it serves 3,000 subscribers in Northwest Iowa. It was founded in 1990 by Art and his brother John. Art is the editor, John is the publisher. Art’s wife, Dolores is the photographer and son, Tom is a, or the reporter.

Art’s own specialty is editorial writing. I have to say, just as a personal side, I started my career in daily journalism as a reporter in a small paper in another region of the Heartland, Casper, Wyoming, which I imagine has some cultural affinities of rural Iowa and that is far from the ocean and there are white Republicans as far as the eye can see.

I can tell you that all those things Americans tell themselves about this deep value we place on dissent and independent expression is about as truthful as the business we tell ourselves about liberty and justice for all. People in this part of the world, that part of the world, take words very seriously. They use fewer of them and they place a great deal of weight on them. You need to watch what you say.

For Art Cullen’s tiny paper to survive, while he takes the liberty of pointing out the hypocrisy and foolishness of local officials and the destructive environmental effects of the policies they champion all for a community of 10,000 at a time when the local press is vanishing is an accomplishment worthy of national recognition, which is what the Pulitzer board thought.

Every year the Pulitzer overseers meet to decide on the awards. They take a few minutes out from their usual practice which is awarding Pulitzer Prizes to the New York Times, the Washington Post and nowadays, the New Yorker magazine. They take a moment to recognize quality publications, a little renown. Usually, they’re in the outback and often the awards come as a backhanded recognition to the fact that a particular community was devastated by a hurricane, earthquake, volcanic eruption, fire or flood.

Sometimes, the award is given for clarity and courage of the journalism as it was in 2017 for the Storm Lake Times when Art Cullen received the Pulitzer in editorial writing. I encourage you to check out Art’s work. It’s archived in the Pulitzer website. When I had read it, what I found was it wasn’t just a collection of well-reported, closely argued essays. I was struck by something I didn’t expect to see and I don’t expect to see in passionate writing and that is kindness.

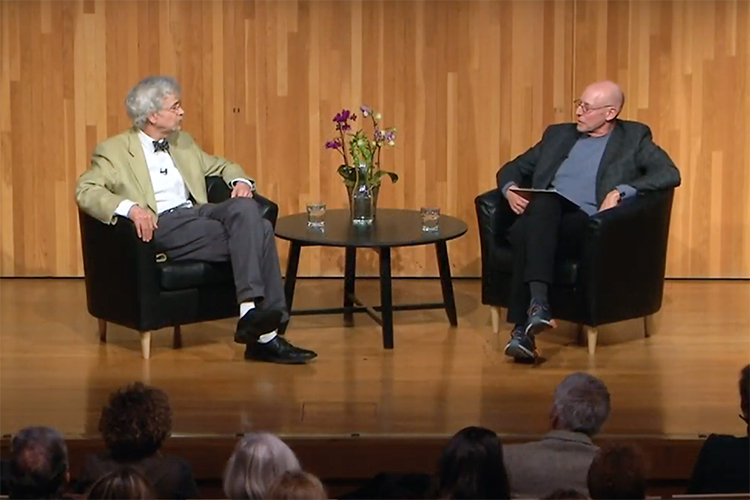

No matter how thoroughly Art disapproved on what he found people had done and how cavalierly they had ignored his inquiries, he treated them with a courtesy and compassion that I find unusual and especially praiseworthy. Maybe it’s those qualities as much as the rigor of his analysis that makes his prose so truly persuasive. It’s a great honor now to turn this over to Michael Pollen and Art Cullen, who will come up and you will have an opportunity, I believe the format will be when you’re through talking. You’ll open it up to questions and we’ll have a microphone.

Please wait for the microphone to come to you before you speak because we’re recording all of this. Thank you very much. Enjoy the evening.

Michael Pollan: Thank you, Ed. Thank you very much, Ed. Thank you all for coming. This should be an interesting evening. I think it’s going to provide insight into several different things that we’re all interested in including what’s going to happen on Monday night, when the Iowa caucuses take place. I want to start with a little housekeeping and specifically to take this opportunity since Ed will be stepping down as dean at the end of this semester to publicly express my gratitude to him for his leadership, his support.

It was interesting, he was talking about kindness. His all-around decency and menschiness, these past few years. Please join me in thanking Ed Wasserman.

I also want to thank Julie Hirano who you’ve seen racing around with microphone. She helped us set up this event and got out the word to you. Malia Wollan who directs the fellowship and whose idea this was, actually, to bring us here together to meet Art.

Art Cullen, welcome to Berkeley.

Art Cullen: Thank you, Michael.

Michael Pollan: Yeah. Your first time here?

Art Cullen: Yes. First time West of Omaha.

Michael Pollan: We’re going to start out just to give you a little map. We’re going to start out talking about journalism and some of the challenges of local journalism today. Then, I want to move in and talk a little bit about agriculture and the farm vote. Then, we’ll move into a full-fledged discussion of politics. I’m really eager to hear what your sense is, what’s likely to happen on Monday and your own endorsement. We’ll wait. We’ll reveal that later. Okay.

By one estimate, I just bumped into online, the U.S. has lost one in four newspapers in the last 15 years. Most of them weeklies and there are now 200 counties in America that have no newspaper, whatsoever. They’re news deserts. Buena Vista County, your county, is not one of them. It has the Storm Lake Times as Ed was telling us. Will you talk a little bit about your path to what brought you to founding a newspaper? What was there before and how you ended up in journalism? There are a lot of young journalists in the room.

Art Cullen: Thanks. Thanks for having me. It’s great to be here. I went to school at the College of St. Thomas in Saint Paul, Minnesota and I was in the first post-Watergate class of reporters. We were the second largest major at St. Thomas then. It was an all men’s school, only behind business. I couldn’t get a job at any newspaper but my brother was able to get me hired in Algona, Iowa which was our ancestral hometown.

I started out working under my brother in Algona. I worked at newspapers then in Ames in Mason City, Iowa. They’re both daily newspapers. Algona was a twice a week newspaper. I cut my teeth at Algona and then moved on to these dailies. John and I separated. John, he had left the Algona newspapers and had returned to work at Buena Vista University. We say Buena Vista in Iowa.

Michael Pollan: Pardon me.

Art Cullen: Madrid and Nevada. He’d gone into work at public relations trying to take a break from newspapers at Buena Vista. He missed the soapbox. He went into the storm like pilot Tribune one day, the incumbent chain on newspaper and asked the 22-year-old publisher if he could buy the newspaper. The publisher told John that he didn’t know enough about community journalism to run a newspaper. John has spent 20 years in newspapers.

He got so mad, he walked out the door and decided right that day he was starting a newspaper in Storm Lake. He called me and said, “Come home, we’re starting a paper.” I said, “Look, take your TIAA-CREF pension and hide amid the Ivy vines. Nobody will ever find you and forget about it.” Then, two months later, I was working with him in Storm Lake.

Michael Pollan: This was in 1990?

Art Cullen: 1990, right. We started out as a weekly. Then, we went daily for a year and lost about $120,000. Then, quickly reverted to twice a week. We’ve been twice a week ever since. We had a high of about 4,000 circulation, paid circulation. Now, we’re down to about 2,800.

Michael Pollan: Lots of papers like yours have gone under.

Art Cullen: Yes.

Michael Pollan: What’s your business model? What has allowed you to survive even as you may be struggling?

Art Cullen: Eating rice. For example, right now John is collecting social security. He works for free.

Michael Pollan: You’re really inspiring the journalists, the young journalists. That’s not an option until they’re 62, I think.

Art Cullen: Or 67, yeah, actually. My son, Tom, gets paid Catholic school teacher wages. Right now, community journalism is existentially challenged. There are papers going down left and right because we’ve been Walmartized. We get an insert from Walmart once a quarter maybe and they eliminated 50 businesses that used to advertise with us. We’ve lost the car dealers to Facebook, both the Ford and Chevy dealers. That’s 100,000 in revenue gone.

We felt pretty good because our circulation has maintained pretty well. We’re actually starting to tick-up a little bit this year in paid circulation, maybe 90 copies, 90 subscriptions, on base of 2,700. That’s considered a major victory right now in journalism, in newspapering.

Michael Pollan: You have a group of people that pay $70 a year?

Art Cullen: Yeah, $70 a year for subscription. There’s about 2,300 subscribers and then we sell about another 400 copies on the newsstands twice a week at a dollar a pop. We made $2,000 this year. The year we won the Pulitzer, we lost 70,000. That’s when we lost our car dealers and furniture. That’s really when Facebook and Google really cut the rug out from under us.

We’ve made $2,000 this year. It was a major victory. We’re about ready to spend it all on champagne and hotdogs. Then, we got a notice from Wellmark Blue Cross and Blue Shield that our insurance rates are going up for the second year in a row, 24%. Before the Affordable Care Act, our rates were going up 68 and 78% a year.

It slowed now to 24% a year, that’s $42,000. We started out the year 40 grand in the hole. That’s a lot of $70 subscriptions. We frankly don’t know what we’re going to do. We always pull a rabbit out of our hat. I don’t know.

Michael Pollan: There’s a pickup in a presidential campaign year?

Art Cullen: No. They don’t. They just buy TV ads and they just cutout print. We get some ads from a certain candidate we endorsed. We wish we could have endorsed them all.

Michael Pollan: The New York Times tried that.

Art Cullen: Right. Right.

Michael Pollan: The president for that.

Art Cullen: Yeah.

Michael Pollan: There you go. I’m kind of curious, you can tell us a little bit about the demographics of this region you’re in, but your editorials are fiery and very progressive. Does that create business problems for the paper or do you lose advertisers of what you were writing?

Art Cullen: We’ve lost all the advertising we can lose, I think. Honestly, I kind of took the point of view, these editorials were about surface water pollution in Iowa. We were taking on basically Monsanto Farm Bureau and the Koch brothers. That’s not a very good business strategy in Iowa.

Michael Pollan: Did you pay a price for that or you’ve already paid?

Art Cullen: No, because honestly, we lost all our ag ads 20 years ago with consolidation. Monsanto’s marketing and Pioneer marketing directly. By the way, when you win a Pulitzer, you can wear white socks with dark pants. We lost all our ag advertising 20 years ago with consolidation because they’re marketing directly to farmers. There’s half as many farmers today as there were in 1980. There’s so few of them. You can call them all on the phone. We lost all that business. We really did take the attitude that, “What the hell, what do we got to lose?”

Michael Pollan: That gave you a certain freedom?

Art Cullen: Me and Bobby McGee, right?

Michael Pollan: That’s it. Help us with the demographics of this town. Our image of Iowa is that it’s very white and I gather that’s changing.

Art Cullen: Yes.

Michael Pollan: Who did it vote for in the last election?

Art Cullen: The county voted for Trump but Storm Lake proper voted for Hillary. Storm Lake, our elementary school is about 90% immigrant. It’s a meat-packing town. There’s 3,000 families processing turkey and pork in Storm Lake.

Michael Pollan: This is for Tyson?

Art Cullen: Tyson, yup. Average wage is about $18 an hour, nonunion. About 70% of those of our elementary school are Latino. Our congressman is a guy by the name of Steve King.

Michael Pollan: We’ve heard of him.

Art Cullen: Right. He’s a racist, a jerk and Storm Lake is blue. It voted for Barack Obama twice. I think Obama won Buena Vista County the first time and lost it the second time but it’s an aberration when a Democrat wins Buena Vista County. Storm Lake’s vote has drowned out by a rigorously high turnout among older Republican voters. We live in the fourth congressional district, 39 counties of Northwest Iowa, a very conservative American reform that’s Dutch reform. Missouri Synod Lutheran, Roman Catholic, German, Swedish, Dutch and very conservative.

Michael Pollan: What about the immigrant population, are they eligible to vote? Do they vote?

Art Cullen: There’s about 2,000 Latinos out of a universe, I think, of 11,000 voters in our county that are registered to vote. I can’t remember the number how many there are in the district but there’s a sizeable Latino population in Sioux City, which is also a meat packing center. These immigrants have really rejuvenated Storm Lake. If were not for them, 67 of Iowa’s 99 counties, two-thirds of our counties, have lost population every year since 1920.

Michael Pollan: Wow.

Art Cullen: We’re really turning the tide. We’ve been very supportive of the immigrant population because the town wouldn’t exist were it not for them.

Michael Pollan: We automatically assume that editorials attacking big ag or agribusiness would be unpopular among Trump supporters. Is that necessarily how the politics plays out?

Art Cullen: No, I’ve never heard a farmer praise the chemical company or the seed company that just raises seed prices 20% or told him he couldn’t grow his own soybean seed. No, I’ve never heard a farmer say, “God, I love Monsanto.” Have you?

Michael Pollan: No. Once we talked to farmers? Even the ones who use their products.

Art Cullen: Right. They have to use their products.

Michael Pollan: They feel like they’re trapped by a monopoly.

Art Cullen: They’re forced to.

Michael Pollan: I remember reporting on farmers who were using GMO potatoes in Idaho. They’d take me to see their big dealer farmer. The farmers are often dealers to their neighbors. There was a Monsanto minder with me actually at this interview and I said, “How do you feel about Monsanto and this future of food?” He said, “It’s the future. You got to go with it, but it’s one more noose around my neck.”

The woman from Monsanto turned white. There is a lot of resentment of agribusiness. I want to talk a little bit about the series that you wrote and won the Pulitzer for because it seems to me it’s going to sound a little granular at first, but it really gets at a lot of issues of agriculture in the Corn Belt and climate change and the alignment of forces in a state like Iowa. Just take us through, there was one big story that basically you followed over the course of more than a year, I guess.

Art Cullen: Yeah. Actually, it was a lawsuit that was filed by the Des Moines Water Works who supplies drinking water to 500,000 central Iowans. We are upstream in Northern Iowa. I had been on a 20-year campaign to save our lake from sedimentation. God made it 24 feet deep and then, we’ve gotten it down to seven feet through poor soil stewardship. Soil erosion was just filling and it’s filling in all these Prairie Pothole, glacial lakes all over Minnesota, South Dakota and Iowa.

Nobody wanted to talk to me about it. I couldn’t get any farmers to talk about it, agronomists, the Department of Natural Resources, Iowa State University people. Nobody really wanted to talk about the fact that we were just filling in our lakes with Iowa black gold.

Michael Pollan: Which is running off of farms?

Art Cullen: Running off of farms, right. I had these pictures. Our pressman and I drove all over Northwest Iowa taking pictures of these lakes just so that we’d have a record that they once existed. I took these pictures down to a meeting of the Iowa Environmental Council in 2013. I was showing them and this guy sitting next to me on this panel said, “We’re going to sue your county.”

It was Bill Stowe who was the CEO of the Des Moines Water Works. I said, “You’re going to sue us for what?” He said, “For polluting the Raccoon River with nitrate,” that is from nitrogen fertilizer. Northern Iowa at one time was all slew in tall grass prairie and my grandfather came in and drained the large share of it. They laid drainage tile about three feet underneath the ground and buried it down there about 80 feet apart. Water leaches down and it goes into this corrugated pipe and that pipe leads to the river and then it goes to Des Moines, where they built North America’s largest nitrate removal system because we apply anhydrous ammonia to the land to grow corn, and that is nitrogen.

We also apply manure which includes phosphorous and nitrogen, P, N, K, phosphorus, nitrogen and potash. Those are the three critical ingredients for corn. In Iowa, we wore a suspender with our belts, so we’ll put pig manure on top of anhydrous ammonia just to make sure we’re going to get 200 bushels per acre out of that corn. Then, about 30% of that nitrate loads ends up in the Raccoon and Des Moines rivers where it’s creating a toxic stew in the Saylorville Reservoir or just North of Des Moines.

They can’t get rid of the cyanobacteria. Nitrate levels are about a three times higher, at least on average, than the recommended by the University of Iowa College of Public Health. The Raccoon Rivers run about 14 milligrams per liter of nitrate and the University of Iowa recommends five milligrams per liter. In Rock County, Minnesota which is just over the Iowa border, it’s 70 milligrams per liter. This doesn’t only lead to Blue Baby Syndrome but it also, we believe, leads to a Parkinson’s disease, Lou Gehrig’s disease and all sorts of neurological disorders.

I know three 2,000 acre farmers who have MS, Parkinson’s disease and one of my best friends who died of Lou Gehrig’s disease, all I believe because of their exposure to nitrate. The Des Moines Water Works sued Buena Vista, Sac and Calhoun counties. These are all adjacent counties in Northwest Iowa in the buckle of the Corn Belt. Agriculture is exempted from the 1972 Clean Water Act because its non-point solution. It’s not a sewer pipe. It’s coming from disparate places, all sorts.

How can you regulate one farm and not the other? There is no regulation. Agriculture is exempted from the Clean Water Act. The Des Moines Water Works said, “There is this drainage tile, this corrugated pipe underground that is leading to the Raccoon River that is a point source of pollution.” They demanded that these strange creations under Iowa law called Drainage Districts, which are administered by the counties, 99 counties, and the trustees of these Drainage Districts are the County Board of Supervisors or County Commissioners.

The only authority they have is to improve the drainage. The only authority they really have is to blow up beaver dams. The Iowa Supreme Court rule that since they had such limited authority, they couldn’t be sued. It struck out money damages. Then, a federal district court judge shortly thereafter dismissed the lawsuit because the counties lack standing to be sued.

Michael Pollan: Along the way, they mounted a very elaborate defense.

Art Cullen: Right.

Michael Pollan: It’s really what you focused on.

Art Cullen: Yes. My son, Tom, he’s the spear catcher. I said, “Tom, since this is a pollution lawsuit, the counties aren’t going to have insurance coverage to cover their legal defense. Why don’t you go ask the Board of Supervisors who’s going to cover their legal? Are they going to raise taxes? Are they going to assess the drainage districts, which is assessing the farmers who have land in that drainage district?” He went down and asked the Board of Supervisors, “How are you going to pay your legal expenses?” They said, “Never mind, we have friends.”

Tom came back and reported that. I said, “Go back and ask them who their friends are? Take another arrow.” I love sending troops into battle. They said, “Are you hard of hearing? We have friends and it’s none of your business who our friends are.” The citizens of Buena Vista County, the taxpayers of Buena Vista County, were being represented essentially by unknown foreign interests. We demanded to know who they were.

We joined with the Iowa Freedom of Information Council. It’s a nonprofit group that tries to promote transparency in government and demanded that they release their list of donors and they refused and refused and refused. Through our own reporting, we found out who the main donors were, guess who? Monsanto, the Koch brothers and Farm Bureau.

We wrote a series of editorials over a two-year period urging A, transparency, B, mediation between agriculture and the environment and then C, moving toward a new agriculture that’s sustainable. Ten of those editorials from 2016, I thought, this is kind of a David versus Goliath thing. By the way, the counties finally had to withdraw from this legal fund because they realized they were in violation of the Iowa Open Records Law and that donors in fact are public records.

They had to withdraw from the fund or release the names of the donors. They withdrew from the fund. We gained a Pyrrhic victory. Agribusiness, the agrichemical complex, got the lawsuit thrown out and they spent $1.7 million of dark money doing it. We were able to get that last 100,000 anyway out of the federal court system. We made our point and we got them to stand down. Then, I selected 10 of these editorials and thought, maybe I could enter these.

We don’t enter any contest. For the first time, I entered the Pulitzers and I asked John if he’d give me 50 bucks. He said, “Are you crazy? You’re never going to win a Pulitzer.” I said, “I’ve prayed to St. John Bosco, Patron Saint of editors and pressman. He’s assured me that we have a good shot.” He said, “All right.” He handed over the 50 bucks.

On April 9th of 2017, they were going to announce the Pulitzers. I asked my wife, Dolores, if she’d give me a haircut. She said, “Why?” This was on Sunday and I said, “On Monday they’re going to announce the Pulitzer Prizes and we’re going to win it.” She said, “Why?” I said, “St. John Bosco told me so.” I’m an Irishman. There are, I don’t know, like 22 journalism categories for the Pulitzers and editorial writing is number 18.

That 2:00 p.m. on Monday, I dialed in to pulitzer.org on live stream and they go through the list, the New York Times investigative reporting. Wall Street Journal explanatory reporting. Number 17, Peggy Noonan from the Wall Street Journal for commentary. I said, “They’re going to call my name next.” Sure as hell, number 18 it said, “Art Cullen from the Storm Lake Times.” Yeah.

Michael Pollan: You could have jinxed it with that haircut.

Art Cullen: Yeah. I shot through the stained ceiling tiles and said, “Holy barnyard up at that John. We won, we won.” He said, “What did we win?” He thought we’d won a spool of fishing line or something. I said, “We won that freaking Pulitzers, man.” For the first time in our lives, we hugged. True story.

Michael Pollan: That’s a heartwarming story. It’s also a story that is just such a vid reminder of what happens if you don’t have this kind of local journalism?

Art Cullen: Right.

Michael Pollan: What happens when it goes away?

Art Cullen: Right. Monsanto, nobody, I guess they’re having their way anyway.

Michael Pollan: Yeah. There’s a check.

Art Cullen: There’s a check. The conversation changed in Iowa because of it.

Michael Pollan: How so?

Art Cullen: Because of severe weather in the last three years since that lawsuit, extreme rains that prevented planting and harvesting. Everybody realizes that the reason we need more and more of these drainage tiles in Northern Iowa so we can flood Cedar Rapids given 500 year floods every five years is because of increased precipitation in the upper Midwest, 5% per decade, increased absolute humidity.

These torrential rains are coming down. We can’t go on. We’ve got to get rid of the water somehow. We just keep expanding this drainage system and everybody realized this can’t go on. Now, this conversation is changing about how can we cleanup our surface water and how can agriculture actually lead the way out of climate change or the climate crisis, I should say. It can, but that’s a whole another.

Yeah. I want to get to that too, but at least when I was last in Iowa doing reporting which now goes back several years, you couldn’t talk to farmers about climate change.

Art Cullen: Right.

Michael Pollan: It just was not a topic. You could talk about extreme weather a little bit.

Art Cullen: Exactly.

Michael Pollan: Has that changed? Is there an open conversation about climate change in the whole …

Art Cullen: Yes. Yes. It used to be, there’s a group called, the Practical Farmers of Iowa, who promote what we call sustainable agriculture. Then, there’s something that goes beyond that that’s called regenerative agriculture. They’re active in both those fields as it were.

Michael Pollan: Can you give us a quick definition of regenerative agriculture for people who haven’t heard the term?

Art Cullen: The idea is to restore soil health through more diverse planning and grazing activities rather than relying on this monoculture of corn and soybeans planted in an oil-base. In a seven-year rotation, you’ll plant rye, succotash, Alfalfa, corn, soybeans, and then graze it in grass. You can eliminate chemical usage and eliminate fertilizers to a great degree by using livestock and manure.

By recreating the microbial life in the soil, you don’t need those same levels of nitrogen fertilizer that we’re using. There’s been a whole lot of research done at Iowa State University, which is a great land grant school. That shows, for example, by planting 10% of a field in native prairie, you can eliminate 90% of nitrate runoff. Farmers are paying attention to these things. They don’t want to lose 30% of their nitrogen loads. They’re realizing that this is costing them way too much money.

Especially now with these huge flushes that we’re getting with climate change, the conversation is moving to, “How can we hold this water in place? How can I hold my fields in place?” Tens of thousands of acres in Southwest Iowa are washed out, never to be farmed in my lifetime or even a younger person’s lifetime. Everybody’s getting it because the pace is picking up so fast and you guys in California now, when California and Australia are burning down and it doesn’t stop raining in Iowa, something’s wrong. We’ve got to change. It is changing.

Michael Pollan: You convened a farm summit for the presidential candidates, right? You organize that. I don’t know how many came.

Art Cullen: Five.

Michael Pollan: Five of them came. I’m kind of curious to what kind of ideas did they bring with them? This is the one time of the year where you get national politicians talking about farm policy and agricultural policy. It’s one opportunity for journalists to extract this from them and get them to think about it. What did you hear there and what was exciting?

Art Cullen: Yeah. We co-sponsor with the Iowa Farmers Union and Huffington Post, what was called the Heartland Rural Forum in Storm Lake. We had Elizabeth Warren, John Delaney, Amy Klobuchar, Julián Castro and there’s one other, well, anyway.

Michael Pollan: Bernie Sanders, there?

Art Cullen: No, senior moment. Tim Ryan.

Michael Pollan: Okay.

Art Cullen: Tim Ryan, who was a facet, he really does get it. He really understands organic ag and regenerative ag. Anyway, what impressed me most was the audience of Farmers Union members. They’re in a crisis right now in the Midwest. Suicide rates are at their highest levels since 1985 in the height of the farm crisis, which drove a whole generation of farmers out of business. Wisconsin dairy farmers are drowning in a sea of milk.

Elizabeth Warren, I got to say, came in there with her Rosie the Riveter routine, talking antitrust and regenerative ag, wanting to increase the size of the conservation stewardship program which promotes conservation on working lands 15 fold, 15 fold. That’s $45 billion. This is real. They were talking on stage about a carbon sequestration in the soil and about paying farmers for environmental services and making agriculture rather than a leading contributor to the climate crisis to make it the tip of the spear in the battle against global warming. That was impressive.

Michael Pollan: Did that resonate with the farmers in the room?

Art Cullen: Definitely. Yeah. They were talking about a farmer’s bill of rights breaking up Monsanto. Again, I’ve never heard a farmer said, “I sure love consolidated seed and chemical companies.”

It’s a whole different conversation than we’ve been hearing since Earl Butz, the agriculture secretary in 1972 said, “Plant fence row to fence row so we can feed the world.” What he really meant was, so we can get Monsanto into China.

Michael Pollan: Turning to politics …

Art Cullen: Yeah.

Michael Pollan: …a little further, it seems remarkable today that Barack Obama won Iowa twice as well as the Iowa caucuses in his first election. Then, last time around, Donald Trump won by 10%, nearly 10%. What happened between those two elections? Did the Democrats do things to lose the farm vote?

Art Cullen: Or the rural vote or?

Michael Pollan: Or the rural vote?

Art Cullen: Yeah. First of all, Hillary Clinton never showed up. Yes, the first rule of politics is to ask them for their vote. She never asked the Midwest for her vote. Second, we were flipping the bird at the country. That’s why Steve King gets elected. That’s why Donald Trump gets elected. They’re saying, “All right, screw you people you’ve been flying over us and dumping on us. We’ve been in decline for 50 years now and nobody cares if Waterloo, Iowa slides off the map and John Deere shuts down.”

That explains a lot of it. There is a lot of angst in the Midwest about declining manufacturing wages, half of what they were in real terms in 1975. Barack Obama came along and said, “Hope and change.” Where was it? There was no change. He saved the economy. He was a little preoccupied with the 2008 crash. Materially while Wall Street got bailed out and the insurance companies got bailed out, nobody bailed out Milwaukee or Flint. Then, Hillary just didn’t show up. Bernie Sanders is showing up. He’s bringing in Michael Moore with his Detroit Tigers cap.

Michael Pollan: He got the right cap to wear in Iowa?

Art Cullen: I’d prefer a Minnesota Twins cap.

Michael Pollan: Okay.

Art Cullen: We have no professional team other than the Iowa Hawkeyes. Bernie is actually talking about a political revolution going beyond hope and change, which is what Donald Trump was talking about, was a political revolution of draining the swamp. We’re going to bring those jobs back from Mexico and China. Yeah. Right. We suckered for it, because we’re desperate.

Michael Pollan: How has that worked out? Do people feel Trump has …

Art Cullen: He started a trade war with China …

Michael Pollan: Right.

Art Cullen: …which immediately caused layoffs at John Deere, the largest employer in Iowa, they make tractors. He started a trade war with Europe that really hurt Harley-Davidson in Milwaukee. Then, he started a trade war with China that shaved soybean prices by 30%. Then, he had to bail out. They have these so-called trade adjustment packages for farmers that are bigger than a bail out of Detroit.

Still, farmers are blowing their brains out and hanging themselves in bars, even with that size of bail out 23 billion a year for two years. They’re still losing money. They’ve lost money seven years in a row. They’re fed up. For the life of me, I’ll eat your left shoe if Iowa wins or it goes to Trump again. I just cannot imagine.

Michael Pollan: You really don’t think it will happen?

Art Cullen: I cannot imagine how when the dairy industry is imploding in Wisconsin and Harley-Davidson’s laying people off and snap on tools, they ain’t selling any tools out of Sheboygan. How’s Trump going to win that? This is the land of Follette, Wisconsin. How’s he going to win Michigan? How’s he going to win Flint? Will African-American voters sit on their hands in Flint like they did with Hillary? I don’t think so.

There’s a lot of anger. The bicoastal economies, it looks pretty good. You get between Colorado and Pennsylvania and it’s not very good. Real wages are going down. Like I say, farmers are losing money at rates I haven’t seen since the farm crisis. California’s on fire. I think it was an aberration. I’d like to think.

Michael Pollan: I would too. Like it or not, you’re not only now a newspaper man, but a power broker in national politics. Although the circulation of the Storm Lake Times is south of 3000.

Art Cullen: Yeah.

Michael Pollan: Candidates for president now have to come and kiss your ring. I don’t see a ring.

Art Cullen: Yeah.

Michael Pollan: Another part of you.

Art Cullen: Yeah. Right. Not much of that either.

Michael Pollan: I don’t think there’s anyone in this room who can get Elizabeth Warren or Joe Biden on the phone. What is that like? You interviewed 15 of the candidates.

Art Cullen: Yeah.

Michael Pollan: Three of them showed up in Storm Lake last weekend?

Art Cullen: Right. Yeah. We had Andrew Yang, Bernie Sanders and Pete Buttigieg.

Michael Pollan: How do you make use of that incredible opportunity that so few of us have?

Art Cullen: This time, of course, last time nobody came, except for Martin O’Malley and he played a fine guitar. This time, what I did is I buttonholed every one of those candidates on a plan for regenerative agriculture that is to lead the way out of this climate crisis.

Every single one of them lead by Warren came up with really substantial plans that Beto O’Rourke had gone to school on it. Pete Buttigieg has a very exhaustive regenerative ag plan and a conservation plan.

Michael Pollan: Do they all revolve around paying farmers for …

Art Cullen: Environmental services. Right.

Michael Pollan: Shifting out of commodity subsidies to that?

Art Cullen: Yes. Tom Harkin, he’s a former Senator from Iowa, wrote the conservation stewardship program to replace crop insurance in the system of subsidies that we’ve had. Saying that this is going to be the future of food subsidy in the United States is conservation funding.

Yeah. We’re seeing a shift. Even Joe Biden is talking about tripling the size of the Conservation Stewardship Program. Whereas Warren’s talking about expanding it by 15 fold. By changing the land use in the United States, we can actually mute the entire effect of the vehicle system in the United States. We can suck that much carbon out of the air if we plant grass and rye and succotash and let cattle roam the green hills.

We can solve this problem. We can remove 10 to 15% of the carbon from the atmosphere just by changing land use patterns. Farmers can actually make money. They aren’t indentured slaves to Monsanto.

Michael Pollan: How do they make money under this?

Art Cullen: No chemical costs. No 20% premium to plant Roundup Ready soybeans, Roundup resistant soybeans or Dicamba-resistant soybeans. Even if you don’t want to use Roundup or Dicamba, which are herbicides, you have to buy the herbicide resistant soybeans from Monsanto because your neighbors are all spraying that stuff. To protect your soybeans, you have to make them Dicamba resistant.

They’re all fed up with it. They’re not buying these Dicamba resistant beans anymore. They’re not buying Bt corn, which is genetically modified to resist corn rootworms because they can’t afford it. They’re finding that through regenerative agriculture, they’re making $1,000 where a farmer’s losing $1,000 under the current system because they have no chemical costs. They have the same yields. They suffer no yield loss, rather than getting paid three and a half dollars a bushel for conventional chemically raised corn, you can get paid three times as much for organic corn at $10 to $13 a bushel as opposed to three and a half to four bucks a bushel.

You may think farmers are stupid, but they’re not that stupid. General Mills now is shifting all the contracted wheat acreage in the Dakotas to organic. Kellogg just announced this week that they are eliminating the use of glyphosate, that’s Roundup, on any of their contracted acres.

Michael Pollan: You think we’re really at an inflection point?

Art Cullen: Absolutely.

Michael Pollan: Yeah.

Art Cullen: Yeah. We can fix this. We can solve this problem.

Michael Pollan: That’s the most encouraging news I’ve heard about agriculture from Iowa in a very long time.

I want to turn in the last few minutes we have and I’ll be turning to you for questions soon. Students first, I’d love to recognize them first. We keep hearing that the Iowa caucus voter is very pragmatic creature. That’s the story that reaches to us. That electability is their first consideration when they’re looking at this democratic field because of the importance they feel of defeating Trump. Yet, the latest polls all show that Iowa is feeling the Bern.

Art Cullen: Right.

Michael Pollan: Is that a paradox? To me, he seems has electability problems nationally.

Art Cullen: I thought Trump had electability problems. I don’t know. All’s I know is when I was at a rally Sunday for Bernie and I saw guys in Pioneer seed corn cups there that are 60 years old that you never thought would be anywhere near a democratic socialist. There are some Smiths…

Michael Pollan: These are Trump voters?

Art Cullen: These are not necessarily Trump voters. They might have voted for Trump. They don’t wear Birkenstocks. There was young people there. People of color were there. Latinos are so scared of being deported. Even citizens who are registered to vote just don’t show up to see these candidates. They just don’t show up in public, period, because they’re so afraid.

When you live on under Steve King’s reign of terror, you just don’t show up. Julian Castro confirms that. He says. “They aren’t showing up anywhere he goes.”

Michael Pollan: They won’t show up at the caucus either?

Art Cullen: No, they won’t show up. They probably won’t show up at the caucuses.

Michael Pollan: Yeah.

Art Cullen: Also, the caucuses are not something that Latinos would be accustomed to. It’s a curious creation about. It’s designed to be a party building exercise. Latinos aren’t necessarily ones to shove their way around in a room.

Michael Pollan: It’s a very public event.

Art Cullen: Yeah.

Michael Pollan: Everybody is moving. You don’t just vote. Explain how it works.

Art Cullen: Yeah. It’s a delegate selection processes. It’s not really a primary. You go in and each campaign needs to have 15% support in that precinct. There’s four precincts in Storm Lake. Each will go to a church or a fire station and you’ll be sitting with your neighbors. I’m sitting in one camp. Michael is sitting in another camp. You have to have 15% support to be viable.

Michael Pollan: Excuse me, you vote by going to the corner where you’re …

Art Cullen: Yeah, you go to a corner and you go sit under the Bernie side.

Michael Pollan: Everybody knows who you voted?

Art Cullen: Yeah. You’re for Bernie over here. You’re for Mayor Pete over here. You’re Warren over here. Then, Yang doesn’t have 15%. Then, the Bernie people go over and say, “We’ll give you a delegate to the state convention if you’ll come over.” Then, they go to the uncommitteds and say you give us half of your uncommitteds at 30% and you’ll still have a viable uncommitted delegation for the state convention where you’ll get wined and dined as an uncommitted. At the national convention where you’ll get wined and dined as an uncommitted.”

This is all part of a political process that very few people outside of Iowa understand. It’s all about party building and getting people involved in the county conventions, the district conventions and state conventions. You start trading votes, trading support. You come with us. You can break loose if you’ve got 15% at the district convention. You can break loose and go back to Yang. All of these deals were made. It’s really fascinating.

Michael Pollan: Your second choice is very important?

Art Cullen: Second choice is very important. Warren in the Iowa poll conducted by the Des Moines Register leads in second choice. When you see the polls, Bernie had the lead in the last Iowa poll. Nobody pays attention or very few people pay attention to that second choice. They’re about half of that caucus all over the state is going to be undecided on Monday night. Because either their group isn’t viable or they went in uncommitted.

It seems like they’ll break down evenly rather than falling in one direction, like saying falling to Bernie. Everybody assumes that Bernie has some ceiling in Iowa because those Biden people just couldn’t bring themselves to go with Bernie. It’s going to be really interesting to see how it shakes out Monday night.

Elizabeth Warren has by far the best organization in the state. Although, Bernie seems to be turning them out. Pete Buttigieg has reputedly said that he’s worked the rural areas really hard. He has as almost as big a campaign organization as Warren.

Michael Pollan: Will you tell us who you endorsed and what you think is going to happen?

Art Cullen: Yeah. On December 11th we endorsed Warren. Now our TV ad is airing in Iowa now, it says endorsed by the New York Times and the Storm Lake Times.

Michael Pollan: Nice.

Art Cullen: Yeah. I’m a big shot, see. I’ve arrived.

Michael Pollan: At least you made up your mind unlike the …

Art Cullen: Yeah, yeah right, right. We picked her because, again, she really led the way in the discussion of agriculture, rural affairs, antitrust. As I told the Boston Globe, you can look out for Boston. We got to look out for Storm Lake. When it comes to rural America, there is no candidate who is her rival in my opinion. She calls herself Betsy from Oklahoma. There is more Oklahoma in her than there is Harvard, I’d say.

Michael Pollan: That’s a lucky thing.

Art Cullen: Yeah.

Michael Pollan: Okay, let’s turn to the audience. Wait for a microphone. Julie, see that hand up there in the red shirt? Thank you.

Audience 1: Thanks for your reporting and everything. I haven’t heard a lot about regenerative farming from the Midwest and from central part of America until actually last week when I heard about a farm called Coyote Run in Lacona, Iowa run by a farmer named, I think, Matt Russell.

Michael Pollan: Matt Russell, right.

Audience 1: Yeah. He brought Biden …

Michael Pollan: Yup.

Audience 1: Kamala Harris. It sounds like people are coming to …

Michael Pollan: There’s a loose conspiracy going on.

Audience 1: Exactly. I haven’t heard about this. In fact, 10 years ago, when I read Omnivore’s Dilemma, I just kept reading about how we’re just locked by Monsanto and oil getting into our soil and everything. My question is how much percentage-wise do you think farmers are coming onto this whole idea of regenerative farming in Iowa and in these states?

Art Cullen: Yeah, as usual, one of my thoughts trailed off. I was talking about the practical farmers. Thirty years ago, they were considered freaks and they would get 20 people at their annual field days. Now, they’re getting a thousand people at their field days. I’ve seen crowds of 150 in Northwest Iowa, Steve King’s backyard. Again, these are guys with their backs up against the wall and they’re looking for anything they can do to cut costs and stay alive.

They’re showing up at these field days interested in winter rye and holding nitrogen in place and…

Michael Pollan: You mean through cover crops?

Art Cullen: Through cover crops, planting cover crops, and so it’s changing rapidly because of cost structures and extreme weather. I think that most farmers, I would say, in fact, the Rural Life Poll showed that 60% of Iowa farmers would do more conservation practices if their landlord would let them. The problem is the people living in California, you own all that Iowa farm land, they like those checks.

Michael Pollan: Why would they be against conservation practices?

Art Cullen: Because they don’t understand. They think that if you spray it with Roundup and plant corn automatically you make money. You cannot tell that widow that, “Hey, we’re going organic on your farm.” Or go ahead and try and tell the banker that. Now, the bankers are starting to get up on it. Finally, Iowa State University is, even the extension service, is now preaching it. Although the Iowa legislature did eliminate funding for the Aldo Leopold’s Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State, the first sustainable ag center in the country. They eliminated the funding for it just because of the Des Moines water works lawsuit just out of spite.

Michael Pollan: The Farm Bureau, which is not identical with farmer’s interests, as you know. A lot of people on the coast assume when they hear Farm Bureau, that’s farmers talking.

Art Cullen: It’s an insurance company.

Michael Pollan: Yeah, exactly right. To get their insurance policy, you have to join. They tend to represent the interest of agribusiness more than the farmers. Nevertheless, they’re still fighting a lot of these changes that you’re talking about. Yeah?

Art Cullen: Right. They are. Even the Farm Bureau at one time was advocating the idea of carbon sequestration and paying farmers for environmental services. It’s pretty hard to say to a Farm Bureau member, “Would you like a check for $300 an acre? That’s $100 more than you’d make anyway just to do nothing but plant grass?” I think every farmer would say, “I’ll take that check.”

I think, an answer to your question, most farmers want to do the right thing if they only could, but they’re locked into this ag supply chain. The bankers are in there, the landlords are in there, Monsanto is in there, Farm Bureau, all the farm publications. You got to have 200 bushel corn. The only way to get there is with Roundup and nitrogen, anhydrous ammonia, which is a byproduct of petroleum, the petroleum industry.

Most farmers want to do the right thing and they’re miscast as these enemies of sound stewardship. The fact is that they don’t own the land.

Audience 1: Do you think that most farmers know what the right thing is now like?

Art Cullen: No, but they’re getting there real fast. This campaign has sharpened the focus. What’s really sharpened the focus is this extreme weather. When you can’t harvest or plant your corn, it gets your attention real quickly. They realize, we’ve got to do something different. We’ve got to be able to hold the soil. They’re starting to realize now because they’re valuing land now in a different way, that because of its depletion, its soil depletion. It’s actually showing up in land values now.

Wheat yields are declining 5% a year in China because of soil degradation. Protein content in Iowa corn tests is showing study declines because of soil degradation. Everybody’s getting onto that. Everybody’s starting to learn about it now.

Audience 2: Can you talk a little bit about the work to create a moratorium on large animal farms that’s happening in Iowa right now? There’s a moratorium they’re working on to …

Art Cullen: They’ve been talking about moratoriums on hog confinement buildings in Iowa since heck was a pup. It’s not going to happen. Nothing is more sacred in Iowa than a confined hog. It’s just not going to happen. What is going to happen is I’m convinced that the entire livestock confinement system is going to fall under its own weight to disease. We can’t use the antibiotics like we used to and there was avian flu virus swept through Minnesota, South Dakota and Iowa in 2015 that killed five million laying hens in Buena Vista County alone and wiped out the Turkey industry in Minnesota. Completely just wiped it out.

It’s going to happen again. People who ignore the 1918 flu pandemic and think it can’t happen, but it did happen in 2015 and it’s happening right now in China with the African swine flu. You just can’t have that kind of density anymore and sustain it. The moratorium, nature is going to impose the moratorium well before the legislature does.

Michael Pollan: Yes.

Audience 2: Quick follow up to that. Why is there willingness to sort of see a difference in changing practices in growing corn and growing winter rye and all of that, but not in the livestock industry? What’s the difference?

Art Cullen: The farmer doesn’t own the hogs. They’re owned by the Chinese and the Brazilians. Smithfield is owned by the Chinese, they own 40% of the hogs in Iowa. That’s why. It’s because the livestock system is not controlled by any producers. It’s controlled by producers on the ground. It’s controlled by the Chinese, JBS out of Brazil and Tyson. To a lesser extent, Cargill and a few other players. That’s why confinements. It’s all part of the vertical integration of the livestock industry.

Michael Pollan: The farmers are growing hogs under contract to those companies?

Art Cullen: Yeah. Right. The farmer goes out and gets a loan on a building to fill it with Smithfield hogs, Chinese hogs, who we’re in a trade war with. Then, he takes out a loan and by the time that building is shut, he’s paid off the loan, has nothing to show for it. He got about 15 to 20 grand a year for managing three hog buildings with a thousand hogs each. He’s just in control of the light switch. Farmers aren’t making those decisions about confinement that’s being made in Springdale, Arkansas and Beijing.

Michael Pollan: Where’s the local political support for sustaining that system? It doesn’t seem to offer much to people in Iowa.

Art Cullen: They own the Iowa legislature. I mean there’s something called state capture that the Koch brothers dreamed up through an outfit called the American Legislative Exchange Council.

Michael Pollan: ALEC.

Art Cullen: ALEC. They’ve taken over the Iowa judiciary, the unseated three Iowa Supreme Court justices for voting in favor of gay marriage. That was the work of outside interests. They’ve taken over the legislature, the governorship. They did the same thing in Wisconsin. Wisconsin started to fight back and elected Tony Evers, thank God, in the last election over Scott Walker. They did it in Kansas. They did it in Iowa. They did it in Wisconsin. Then, they take over the state university systems.

Art Cullen: Now, Monsanto is the main funder of the genetics program at Iowa State University. It’s the leading crop genetics program in the country besides Berkeley. They control the whole system.

Michael Pollan: Yes.

Audience 3: Hi. Thanks for being here.

Art Cullen: Thanks for having me.

Audience 3: Yeah, I hadn’t thought too critically about the role of a newspaper’s presidential endorsement until New York Times split their vote last week. I’m wondering if you could share some insight historically, practically is newspaper’s presidential endorsement a public service? Could it be a disservice? Does your answer change when a paper circulation is a couple thousand versus hundreds of thousands or millions?

Art Cullen: First of all, I question how much endorsements matter. I’d point out president Bill Bradley, who we endorsed. President George McGovern. I don’t know who, I suppose the New York Times endorsed Hillary, didn’t they? We did. Although she never came.

Michael Pollan: He’s still feeling that.

Art Cullen: Yeah, I don’t get over that. I think it’s still worthwhile to do it because we do get a special seat. I got to spend 45 minutes to interview Bernie Sanders or Joe Biden. It’s fun to do. I think we have an obligation to say, “Look, we got this front row seat and here’s what we think.” I also am old-fashioned enough to believe in institutions and that institutions are important. I still believe that a community newspaper or a state newspaper is an institution and has special responsibilities. Whether it matters or not, it’s important to do.

Michael Pollan: Okay.

Audience 4: Thanks. Would you comment on the trade deal with China and whether it will…

Art Cullen: How much time you got?

Audience 4: …whether it will operate to be that bailout for the Midwestern farmers to enable them to continue agriculture as is because China’s obligated to buy so much American produce.

Art Cullen: Okay. First of all, Trump said that they were going to buy $50 billion worth of agricultural products. You’d better buy bigger tractors and more land. You know how much the soybean markets went up that day? They went down 9 cents because they think he’s a liar. They know he’s a liar. China’s only bought 17 billion or 20 I think maybe. Anyways, about half that much is their record year, which was 2015, I think.

Michael Pollan: They found a new source of supply.

Art Cullen: Yeah. Now, they’re ripping up the rain forest, burning down the rain forest in Brazil so they can grow or graze it and then use the savannas to grow soybeans. We’ve lost those markets forever. What Earl Butz started, Donald Trump ended. Those markets aren’t coming back for those export markets. That’s a big part of why farmers are paying attention to a different way of being paid for environmental services rather than banking on exports, 30% of our dollar, it comes from the export markets.

We just lose at the game every year. We’ve been losing at it since 1972. We have half as many farmers and twice as much exports. What do we got to show for it? Nothing. They’re saying, “Okay, maybe there is a different way to do this. Maybe if we got paid for environmental services rather than exports, maybe that makes more sense.” They’re starting to think that way.

Michael Pollan: Okay.

Audience 5: Hi. Thank you for being here first.

Art Cullen: Thank you.

Audience 5: I’m wondering if you think it’s possible to attain this land change use that you’ve been talking about towards regenerative agriculture without changing land ownership and the business model of agriculture and only with market incentives and policy.

Art Cullen: Yeah. Basically, if you bid a dollar more for grass over corn, plant grass. The landlord will, if the farm manager tells that widow lady in California that you’re going to make $10 more planting grass instead of corn and the banker says it’s okay, they’ll plant grass. The bankers are figuring out that if they want to keep their assets in order, their loans, then they’re going to tell these farmers to cut their chemical costs. They’re starting to have those conversations.

They have about one more year before we start to get into another full-fledged farm crisis. Those conversations are going on right now with farmers about what are you going to do next year to breakeven? We’re probably going to have those conversations with our banker ourselves this year.

Michael Pollan: Everything depends on having a very different, radically different kind of farm bill, right?

Art Cullen: That’s right.

Michael Pollan: It changes. We already pay farmers a an enormous amount of money.

Art Cullen: They’re doing it now even with the meager subsidies that they do get, they’re doing it just to cut their chemical costs because they’re seeing these guys that are planting cover crops and they’re completely eliminating their use of herbicides, just by planting winter cover crops like rye. You plant it in the fall and say September, so it holds that soil and water in place and the fall and winter flushes.

They’re finding that by using these cover crops, they don’t need to fertilize in the fall or spray herbicides in the spring and that they can get in a lot faster because they don’t have to do all that poisonous work

Michael Pollan: Yes.

Audience 6: Hi. Yeah, thank you again so much for being here. I’m also really curious about regenerative agriculture. I immediately wonder what that will feel like as like for consumers?

Art Cullen: Healthier food. There’s a book called Omnivore’s Dilemma that talks about the damaging effects of feeding cattle corn and feedlots, which by the way are unsustainable. I’ve been to Dodge City, Kansas and Garden City, Kansas. You go into Dodge City and there’s 10,000 steers that land right outside the city limits and it smells like burnt hair and cow shit. The Ogallala Aquifer is going dry and they’re not going to be able to ship in corn to Kansas anymore and feed those cattle at Dodge City.

Those cattle are going to have to move north where there’s water and that that’s going to be Canada, Minnesota, Buffalo, New York. Because the Ogallala Aquifer will be drunk dry within 20 years. That slates the thirst of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, the entire … the old west and the cattle trails. That party’s over. Yeah, it is. It’s all going to be forced on and it’s being forced on us very rapidly right now in ways that we don’t even appreciate.

Michael Pollan: Time for one more question.

Audience 7: Hi. Again, thank you for being here, both of you all. You talked a moment ago about how you believed in the importance of local papers. Maybe there’s not an answer to this question, but what’s the next rabbit out of the hat in terms of keeping your paper alive?

Art Cullen: I was asking Michael Pollan about that this afternoon.

Michael Pollan: Did I have a good answer? No.

Art Cullen: No, he didn’t. What the entire industry is trying to do is to switch to what to reader revenue and that is asking you to pay for a subscription. It’s working pretty well for the category killers like the New York Times and the Washington Post. They can make a fair amount of money selling a $10 subscription or a $20 subscription. We can’t. We need $100 subscription because our universe is that much smaller.

It’s pretty tough getting a hundred bucks out of somebody for a newspaper. Especially when half the town can’t read English or Spanish for that matter. They come to the United States with a third grade education and can’t read in their native language. It’s really tough in Storm Lake and I don’t know what the hell we’re going to do. We’re fortunate because I got lucky and won a Pulitzer. I have some opportunities to do stuff that my neighbors down the road don’t have like come here.

It’s an existential crisis and I can’t say that enough. We don’t know if we’ll be in business after this year, honestly. I have a friend and Carroll, Iowa, very similar, an hour away from Storm Lake. At one time, it had the highest household penetration of any newspaper in America. Now, it doesn’t know if it’ll be opened in a year. We don’t know what the answer is. I could get a grant to go to Mexico and do a story, a long form reporting story for the Atlantic. I can’t get a grant to pay my son, Tom, to cover the county board of supervisors.

Michael Pollan: There you go. There it is. Let’s hope you keep doing what you’re doing because it’s incredibly important.

Art Cullen: We’re going to try.

Michael Pollan: Yeah. Thank you for filling us with hope though on some other issues besides journalism. I never thought farming would look more promising than journalism. Perhaps, we’ve reached that point. Will you all join me in thanking Art Cullen?

Art Cullen: Thank you.

[Music: “Silver Lanyard” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Podcast outro: You’ve been listening to Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. You can find more talks with transcripts at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.