Look out, world. Graduating senior Ms. Jules, 67, is just getting started

A mom, grandma and great-grandma, she's known on campus for her love, wisdom and straight A's

May 18, 2020

“I felt like a mother and a grandmother, in a lot of classes,” said Jules Patrice Means, 67, “and you could see in their eyes, “Wow, she’s really trying to help us.’ … I felt a closeness, not just to Berkeley, but to the young people there. And you learn from them, and it keeps you young.” (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Don’t even think of calling her Jules. It’s Ms. Jules, as sociology lecturer Andy Barlow learned the first time he addressed his student, Jules Patrice Means, then age 66, at the start of Deviance and Social Control, a course he taught this past semester.

“Although she is younger than I am,” he said, “she corrected me and said, ‘I want everyone to call me Ms. Jules, in recognition of my role with younger students on this campus.’ I have never called her anything but Ms. Jules since.”

The respect demanded by Means, now 67 and a graduating senior at UC Berkeley, is not only gladly given by those she meets, it’s earned. She’s had a lifetime of challenges — from having a baby in high school to suffering a major stroke at age 60 — that have only made her stronger and better equipped “to do what the Bible tells us: To love your neighbor as much as you love yourself,” she said. “That’s how I live my life.”

Jules Patrice Means hopes that commencement is rescheduled for a later time, and held in person at Berkeley. She ordered announcements, now obsolete, but says she’ll reorder them when the chancellor announces a new date. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Well, there is one hurdle she’s still trying to clear: The loss of this month’s graduation ceremonies, which causes the proud, stylish great-grandmother and sociology major, who received all A’s and one B+ while at Berkeley, to tear up. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, she says she’d paid for “quite expensive” graduation announcements and photos of herself in cap and gown. They now sit in stacks, inside plastic sleeves, on her dining room table in Brentwood.

“My invitations say May 16, and they’re so beautiful,” she said. “I thought about placing a sticker on them with a new date and location, but I do not believe it would look professional. I’ll now have to repurchase all those invites when we get a new graduation date.”

But Means is cheered by Chancellor Carol Christ, whose last name Means said she intentionally pronounces like another name for Jesus “because she reminds me of Jesus, … she’s a really good person and is thinking above the bar.” She said Christ was kind enough to survey 2020 graduates about their preference for a virtual commencement or an in-person one at a later date and told them, “If anyone deserves a graduation, it’s you.”

“When my name is called,” said Means, who definitely does not want an online event, “I will walk across the stage with the utmost grace and feeling that I accomplished my goals at one of the most prestigious universities in the world. And I’m not finished yet. I plan on applying for grad school at Cal to earn my Master of Social Welfare degree. It’s never too late to achieve your aspirations in life.”

“Ms. Jules is the mom, grandma, auntie, or that one lady from your childhood that you could always count on to enrich your life in small, but sweet interactions, each time you see her,” said Tomie Lenear Jr., program coordinator at the Student Parent Center. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

A teenage mother, writing in pencil

Growing up in San Francisco’s Richmond district, a block from Ocean Beach, Means had a stay-at-home mom, a longshoreman dad who successfully bought, renovated and sold old houses, four sisters and perfect grades. But at school, life wasn’t so ideal.

In the late 1950s and early ‘60s, at Lafayette Elementary in the city’s Outer Richmond neighborhood, “I was called every name in the book: tar baby, big lips, stupid, crazy,” said Means. “I went home and told my mother, ‘I wish I was white. I don’t want to be negro,’ which was a word we used in that time period.

“’Why?’ my mother asked. I told her, ‘I’m not accepted. They mistreat me, hit me and call me terrible names.’ ‘You are a beautiful, beautiful, negro girl,’ said my mother. Her name was Marion Silk, and she had great integrity, and a strong work ethic. ‘I want you to always hold your head up high.’ From that day on, that’s what I did. Mother told me to write my plans in pencil, but give God the eraser.”

Later, in high school, that eraser got busy. First, a girl slipped Means a phone number, telling her it was for Means’ biological father, and it was. At 16, Means moved in with her newfound dad, a concrete mason, eager to know him and his wife and children. But when Means got pregnant at 17, he told her to return to her mother.

Instead, Means packed for her boyfriend’s house. His mother invited her to stay, but if it was to be long-term, she told the teens they must marry; they’d only dated a few months.

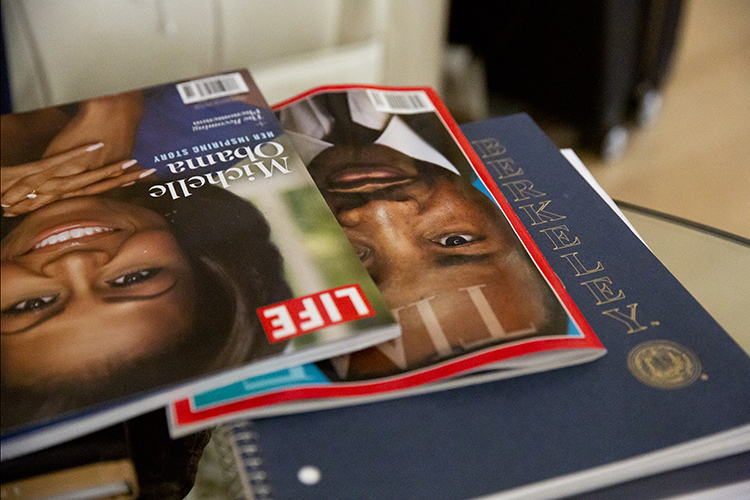

On Jules Patrice Means’ coffee table in Brentwood sits a UC Berkeley notebook and magazines that highlight her two idols, Michelle Obama and Martin Luther King Jr. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

“It was a shameful thing, at least for our family, to have a baby out of wedlock,” said Means. “I concealed the pregnancy really well, wore big clothes, because I didn’t want people to talk bad about me. I felt like I had to get married, so we did, at city hall, before the baby was born, so no one would say anything.”

Means, who’d dreamed of becoming a San Francisco mayor, put away hopes for college, “even though I was a good student, a straight A student,” she said. “I felt my life was going to be terrible, that I’d be on welfare and not able to take care of the baby.”

But Means persevered. She finished high school in 1971, the same year her son was born. Her young husband’s mother died, leaving the couple $4,000 from her life insurance policy, “enough to pay first and last months’ rent at our own apartment and a little old car,” she said.

The marriage didn’t last long, but refusing welfare — “I was able-bodied,” Means explained — she worked two jobs, flipping burgers and caring for an elderly woman. Then, she had a fortuitous chat on a city bus with the daughter of Dr. Leon Kaufman, a then-UCSF physics professor who needed an assistant for his radiological imaging lab experiments.

“Are you afraid of rats and mice?” the woman asked Means. “I said, ‘Oh, my god,’ and my blood pressure went up,” said Means. But the job paid $400 a month, and Means was hired. It was a stroke of luck that, with her full-time job at the lab and a Saturday shift at the restaurant, allowed the young mother, in a tiny apartment of her own, to pay her bills while raising her son.

“When I got (to Berkeley), it was overwhelming, and I was like a deer in headlights. I told (my niece) Elettra, ‘I’m not going to be able to do this.’ I wasn’t used to being on a campus so huge, with all those buildings and people running to classes. And she said, ‘You can do this, Auntie Jules. You’ll be the first person in our family to attend Berkeley, and Berkeley only accepts the best of the best. You did not get in by mistake. Go in there and give it 100%.'” (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Overcoming two strokes and a missing dot

Means had a stroke of another sort in 2010, and again in 2014. By then, she was the mother of four sons, married to her second husband, who died last year, and working as an executive assistant at Ernst & Young, where she was a valued computer and graphical presentation whiz. Recovering from her second stroke was a long road.

“It was on my right side, but it affected my whole left side,” she said. “I couldn’t walk, I couldn’t use my arm, my face had dropped. I stayed in rehab for three months and learned to walk again, but I had a limp. Do you know how depressed a person can be after a stroke? I felt almost suicidal.”

Still, Means determined to “make my face get normal, and I did every face exercise known to mankind. I recited one poem, ‘Sermons We See,’ daily until I could gain mobility in my face and in my legs, and I prayed,” she said. “And I wanted to get off my bed, so I told myself, ‘You never went to college. Take the opportunity to go there.’”

Eventually, she walked down the street and into Los Medanos College, intending to sign up for a yoga class, to strengthen her muscles. But the $3 community college course catalog caught her eye and, wowed by the offerings, she said, “I took a speech class and went from there,” and she went far.

When Jules Means submitted her application to Berkeley, “I almost had a heart attack,” she said. “Honey, this is what I have to tell you: … I never received an acceptance from Berkeley.” Later, when she went to campus to ask why, Means learned that she’d been accepted, but a dot between her first and last name had been left out of her email address, and the news never arrived. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

In 2017, Means earned not one associate’s degree, but five — in psychology, behavioral science, social science, administration of justice, and arts and humanities. And all her grades, from both Los Medanos and Diablo Valley colleges, were A’s.

By then, she’d decided to transfer to UC Berkeley, UCLA or UC Davis, with Berkeley as her first choice. But she picked UC Davis when acceptance from Berkeley failed to materialize. Berkeley had given her conditional acceptance, pending its receipt of her community college grades, but then went strangely silent.

“The (community colleges) did submit my transcripts to Berkeley, and I really wanted to attend, so I told my niece, Elettra Patrice Meeks, to drive me there,” she said. “The lady in the admissions office told me, ‘Ma’am, if you didn’t get accepted, you can just apply at another time.’ But I showed her my conditional acceptance, and my email address.”

Means had gotten in, after all: The email address Berkeley had used to relay her acceptance had missed a dot between her first and last names, and the news never arrived. When she got home, it was in her inbox, finally emailed to the right address, along with an explosion of online confetti.

“It was almost like being accepted to heaven,” she said. “That’s the way I looked at it.”

Sociology lecturer Andy Barlow said he owes Jules Patrice Means “a big debt of gratitude for deepening my understanding of the powerful truths that can be learned in a classroom, especially if we let our most marginalized students speak. I know I speak for the entire class when I say we are so proud of Ms. Jules, and all she has accomplished, because her accomplishments lifted us all.” (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Glammed up and down-to-earth

Alongside her Berkeley classmates, Means said she felt “like a mother and a grandmother.” When one of her study groups wanted to party and asked her to come along and “turn it up,” she said, “I told them, ‘Thank you, but I’m going to turn it down before I go to bed.’”

“Ms. Jules is the mom, grandma, auntie or that one lady from your childhood who you could always count on to enrich your life in small, but sweet, interactions each time you saw her,” said Tomie Lenear Jr., program coordinator at Berkeley’s Student Parent Center. “She’s outlived most of our life circumstances, so the times when we’re troubled are hindsight to her.”

In a sociology lecture during fall semester 2019, Means said a transfer student sitting next to her suddenly rested her head on Means’ shoulder. “I said, ‘Are you alright?’” said Means, “and she said, ‘I can’t do this anymore,’ and walked out of class and left her purse and books. I found her in the bathroom.”

That student was Avalon Ansara, who said Means “not only comforted me, she went to the teacher and tried to advocate for me.”

“She definitely has a mother vibe to her, is very down-to-earth,” said Ansara, despite how “full force, glammed up” Means dressed for class presentations. “Thanks to her, I’m getting all A’s this semester. I saw a lot of darkness at Berkeley because my transition from community college was very hard, but she brought to life for me what a prestigious opportunity it is to be here. … She caused me to love learning.”

She added that Means doesn’t mince words. “You can’t make dumb mistakes around her,” said Ansara, who was warned, “Boyfriends are nice, but grades can lead you to a better place.”

To thank people who helped her achieve her dream of attending and graduating from Berkeley, Jules Patrice Means had certificates of appreciation made, which she’ll present to her supporters. They include Daniel Cabral, a district attorney in Contra Costa County, and Nisha Grayson, a senior vocational rehabilitation counselor for the state. (UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

When another student said, “Ms. Jules, you’re always studying. C’s get degrees at Berkeley, you know,” Means said she didn’t hesitate to say, “Young lady, one day I’m going to be applying for a job against you, and these corporations are asking for transcripts. If I have all A’s and you have C’s, who do you think they’re going to hire? To this day, (that student) remembers me and emails me.”

Even when Barlow offered to grade his students based on the work they did prior to COVID-19 ending classes on campus this spring, Means — who already had an A in his class — insisted on completing her final paper and exam, “and, of course, they were excellent,” Barlow said.

The high academic standards that Means sets for herself, he added, shows that “she deeply understands the power of knowledge for marginalized people. … and her commitment to academic excellence rubbed off on the entire class, and resulted in the class earning the highest grades I have ever given.”

Means said there is much more that Berkeley needs to do to fight racism, including addressing it “right here on campus.” In one course, she said, she had to chide two white classmates who were snickering at slides of sexual cruelty to slaves.

“I’d like to see more professors of my color and classes that relate to African Americans in positive ways,” she said, adding that she’s pleased that campus diversity is one of the chancellor’s top priorities. “We, as a race of people, have a lot to say.”

After getting her master’s degree in social welfare, Means plans to work as a counselor, helping to give voice, and hope, to low-income earners, especially those from minority communities.

“Education is the key to unlocking the doors that prevent people from reaching their goals,” she said. “If I can do it, they can, too.”