Graphic violence online: Campus human rights lab pioneers safer viewing

Lessons in resiliency can counter trauma of seeing images of racial brutality, COVID-19 death

August 6, 2020

To avoid vicarious trauma, students at the Human Rights Center Investigations Lab view disturbing videos together, rather than alone, in their work monitoring social media for evidence of potential human rights violations and war crimes. They also discuss the content and its effects on them. (Photo by Andrea Lampros)

Sheltering in place this spring from the coronavirus, UC Berkeley alumna Pearlé Nwaezeigwe missed her family in Nigeria and said she “felt locked up, all alone” in her Oakland apartment. She turned to social media to engage with the world, but it left her helpless and unhappy.

Her Instagram, Facebook and Whatsapp feeds were bombarding her with painful photos, videos and stories about COVID-19’s dead and dying victims, the murder of George Floyd by a police officer, Black Lives Matter demonstrators injured by law enforcement and the rape and killing of young women in Nigeria.

“It was very traumatic, what was coming up on my screen — people getting shot, screaming, being harassed,” said Nwaezeigwe, who graduated in 2019 with a Master of Laws degree and was a technology policy specialist at Berkeley’s Human Rights Center. “As a Black woman, it was triggering for me, and I realized this was affecting people worldwide, too.”

She responded, with help from Rachael Cornejo and Lili Siri Spira — Berkeley alumnae, like her, in the human rights field — by creating Rated R. The online project offers tactics from the unique resilience training at Berkeley’s Human Rights Center Investigations Lab to help social media users navigate distressing content. The three young women were among some 80 students at the lab each year who mine hundreds of videos on social media for suspected human rights violations or war crimes.

Rated R project creators and UC Berkeley alumnae, left to right, Rachael Cornejo, Pearlé Nwaezeigwe and Lili Siri Spira. (Photos of Cornejo and Spiri by The Right Stuff, photo of Nwaezeigwe by Jamie Shin)

The students gain technical skills and other know-how to confirm an incident’s time and date, the perpetrators and weapons involved, and the casualties and physical destruction. But they also learn to do so safely, both in terms of psychosocial security and cybersecurity.

“Teaching resilience is a priority for us; it’s as important as teaching students to find, verify and analyze online content,” said lab co-founder Andrea Lampros, associate director of Berkeley’s Human Rights Center and the lab’s resiliency manager. “Students don’t know how they’re going to respond to this weighty work until they’re involved in it, so we train them from the beginning about secondary trauma, burnout, what research says makes you vulnerable, and then techniques to mitigate the potentially harmful effects of looking at emotionally distressing material.”

Vicarious, or secondary, trauma is indirect exposure to a horrifying event that can cause emotional, behavioral, physiological, cognitive and spiritual symptoms such as grief, anxiety, nightmares, negativity, cynicism, substance abuse, physical pain and loss of hope and purpose.

Rated R’s upbeat website, which Nwaezeigwe said she designed to be “aesthetically pleasing, with calming and soothing colors, a safe space to go,” offers toolkits to build one’s digital resiliency. In addition to advice on viewing news with graphic content, there are lists to tap for feel-good social media accounts, self-care prompts, academic resources and mental health assistance.

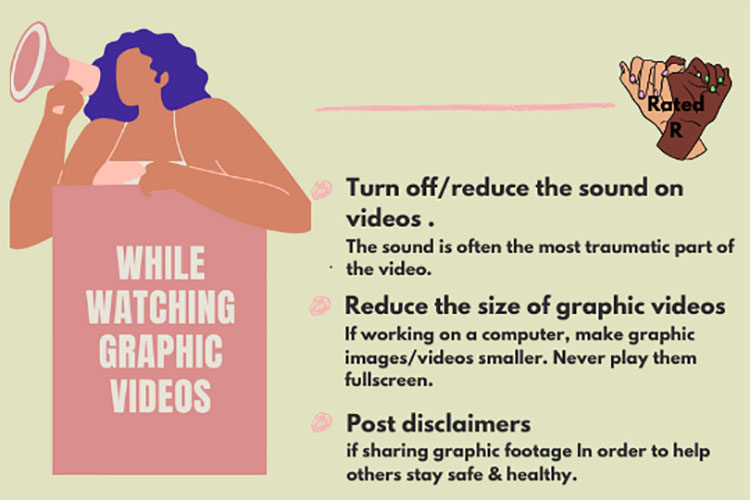

A webpage from Rated R, a site created by Berkeley alumnae trained at the Human Rights Center Investigations Lab, gives safer viewing tips for preparing to watch potentially distressing news videos on social media. (Image by Pearlé Nwaezeigwe)

While at Berkeley, investigating the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar, Nwaezeigwe said she watched “a video of a man being killed, and his body being dragged around. It was shocking, this disregard for human life. But I wasn’t watching alone. I was with a group of people, the audio was turned off, and we’d scanned the video beforehand on a smaller screen. I was glad to have these (resiliency) tools, because no matter how graphic it was, I wanted to give back, to catalog the content.”

Being resilient doesn’t mean “not caring about what you see, because these videos wake you up to what’s going on in the world,” said Cornejo, a 2020 graduate and former student lab manager who is Rated R’s primary content developer and ratedresilient Instagram manager, “but knowing how to watch, so you can avoid vicarious trauma.”

Rated R primarily targets “Black women and other women of color,” said Spira, a former student investigator at the lab and 2020 graduate who constructed the Rated R website. It’s critical, added Nwaezeigwe, that the site influence “and represent Black women, who face sexism and racism every single day. And in most spaces, we’re not represented.”

The site also strives to help keep “all the digital activists fighting injustice from burning out,” said Spira, “to ensure their safety on social media over long periods of time.”

The R in Rated R stands for resilience and “the idea that people need to apply a mental rating, a filter, to watch (graphic news videos), like when you watch a movie,” Nwaezeigwe said. But the R also signifies revolution and resistance, she said, “words that capture what’s going on in the world.

“Rated R is like a gift to the revolution. It’s public service, … to help people on the street and the healers who help the wounded to bounce back and continue the fight.”

Elise Baker, a recent Berkeley Law graduate, recently authored, along with leaders at Berkeley’s Human Rights Center, a report on best practices for safe viewing of graphic news content. (Photo by Ethan Chaleff)

Tried and true techniques for safer viewing

Alumna Elise Baker, who graduated from Berkeley Law this spring, is working to protect digital open source investigators — hired by international tribunals, United Nations bodies and nongovernmental organizations — from vicarious trauma. Last May, she was first author of a paper published in the Health and Human Rights Journal that identified top techniques for safer viewing of potentially distressing audiovisuals.

“As human rights researchers, or journalists, or people in the helping fields,” said Baker, “we’re motivated to do our work because of these situations, but it’s hard to take a step back and realize the news has an impact on you. Overexposure to graphic content only makes things worse; there’s a balance we have to find.”

Surveys were sent to students involved for at least one semester in a digital open source human rights investigation program, either at UC Berkeley, University of Cambridge, University of Essex, University of Hong Kong, University of Pretoria or University of Toronto — all the universities in Amnesty International’s Digital Verification Corps. Because of the work of Sam Dubberley, the corps’ Citizen Evidence Lab director, each school’s program teaches techniques to reduce one’s risk of developing vicarious trauma and provides resources to cope.

Baker’s study found that, when reviewing horrifying video content, most respondents benefited from limiting their exposure to the audio; some listened to music instead. Most of them also reduced their exposure to graphic imagery, such as by minimizing the display size on the computer screen and, before watching a video, clicking through its individual frames to be forewarned of any shocking material.

The majority of respondents also worked with a partner or team instead of alone, took regular breaks from their work to reduce stress and exposure to graphic material, talked to each other to help process extreme content, reflected on the meaning of their projects to stay motivated and created a distinct physical space to work, apart from their personal lives.

Resiliency techniques used at Berkeley’s Human Rights Center Investigations Lab, where students often view citizen videos that include graphic imagery from war zones around the world, include taking regular breaks from work — to reduce stress and exposure to troubling material — and reflecting on the meaning of their work, to stay motivated. (Photo by Andrea Lampros)

From 2013 to 2017, Baker worked for Physicians for Human Rights, documenting attacks on medical facilities in Syria through open source investigations. She saw injured and diseased patients, deceased people and chemical weapons assaults, “but it probably took me an entire year of reviewing before I realized the impact on me. There was no conversation around vicarious trauma at the time.”

“I had nightmares about being in bombings in hospitals, general agitation, and I dissociated with friends. I imagined every bad thing that could happen in unrealistic scenarios,” she said. “There was very little institutional support (for vicarious trauma), so the thing that allowed me to keep working there … was developing strong relationships with my co-workers. We created a space to talk about difficult videos we’d seen, the difficulty of working on a conflict that didn’t seem to be ending. By itself, it was not sufficient, but it helped.”

When deciding whether to watch the video of the May 25 killing in Minneapolis of Floyd, an African American man, by a white police officer, “I made a conscious decision that it’s a really important video, and the fact that it exists has led to this racial justice awakening, but that watching it will do me more harm than it will benefit me,” said Baker.

Worldwide, “the culture is changing,” she said, “but there is still some amount of taboo, a reluctance or embarrassment for people in helping professions to talk about being affected by graphic content out of a fear of being labeled as not strong enough to do this work. The more research we can put out about this, hopefully we’ll help break that taboo.”

Maria Isabel Di Franco Quiñonez, a former student manager at UC Berkeley’s Human Rights Center Investigations Lab, in Hong Kong at the 2019 Amnesty International Digital Verification Corps summit. (Photo by Shakiba Mayeshaki)

Necessary conversations

When Maria Isabel Di Franco Quiñonez first worked at the Human Rights Center Investigations Lab as a student, she was jolted by hateful comments she read on social media by people viewing a 2017 video of Venezuelan protesters being sprayed to the ground with high-pressure hoses. The video had been falsely spread on the internet as one of migrants being pushed away from the U.S. border.

Di Franco, who graduated in May with a political science degree, said one woman wrote, “I have to pay to send my daughter to the water park,” while others “said things like, ‘Good, glad we’re taking care of business, send in the troops.’”

At first, Di Franco, who grew up in Venezuela, didn’t confide in anyone, having been “raised in a culture where these aren’t conversations meant to be had in a professional setting, or at all, that this isn’t an important part of the work,” she said.

But her personal life suffered, and she stopped interacting with friends and her partner as she typically would. “As time went on,” said Di Franco, who worked on many projects at the lab, including mapping destruction in Syria, “I became more understanding about how important it is to engage in these (resilience) practices, that it’s fully irresponsible not to.”

Recently, Di Franco shared those skills via Zoom by leading a three-day workshop in Spanish with Chile’s Datos Protegios (protected data) project, where a team is creating an archive of the October 2019 Chilean uprising. Much of the social media content it has reviewed is of police brutality and protesters being beaten, illegally detained and shot with rubber bullets, which led to hundreds of eye injuries.

“People doing the verification work were dealing with the adverse effects of consuming so much graphic violence,” she said. “They were exhibiting symptoms of secondary trauma” that were being exacerbated by the COVID-19 quarantine.

“It came to me, with COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter, that people are consuming a lot of graphic news content at home and watching so much from their beds, and in a constant cycle … I wanted to help people navigate this space, to feel more secure watching videos and to reduce vicarious trauma,” said Berkeley alumna Pearlé Nwaezeigwe. (Image by Pearlé Nwaezeigwe)

Teaching resiliency beyond campus

At the four-year-old lab, the experience of teaching students about resiliency to secondary trauma will be shared in a book — the working title is Graphic — being co-authored by Human Rights Center Executive Director Alexa Koenig and Lampros, who also have taught resiliency elsewhere on campus, at UC Santa Cruz and to NGO colleagues nationwide. This book is designed to help the general population, in an increasingly virtual world, learn “how to keep themselves safe without looking away,” said Lampros, “how to stay engaged with what’s happening” in the news, rather than retreat or suffer repercussions.

Koenig, who’s previously written about trauma and resiliency in human rights work, said, “One way we began to push back against the stereotype of a resiliency plan being a ‘nice-to-have,’ but not a ‘need-to-have,’ was to place it in a security framework, underscoring the intimate relationship between physical, digital and psychosocial security.

“Struggling psychologically can have a negative impact on day-to-day practices, including adhering to digital security protocols — while the threat of security breaches, whether digital or physical, can have a corresponding negative impact. For human rights investigators, it’s important to think about these issues holistically.”

The lab continues to experiment with ways to counter vicarious trauma. When an investigation of hate speech against immigrants took a toll on students, they held a debrief and dinner to help dispel the cynicism and distress about humanity that was creeping in. They asked each person to say, and to write on a piece of butcher paper they’d placed on a table, what they know is true about immigrants. Words like “strength” and “perseverance” began to cover the page, and the diverse group of labmates, from many countries, shared personal stories, even a grandmother’s song.

Seeing alumnae like Nwaezeigwe, Cornejo, Spira, Baker and Di Franco take into the world what they’ve learned in the lab is “not surprising,” said Lampros, “because Berkeley students are such innovators; they take a holistic approach to trying to change the world.”

“With our resiliency efforts, we’re trying to shift the paradigm of how we work — whether we’re challenging structural racism or investigating human rights — to make it more human and balanced, without sacrificing ourselves and our mental health and well-being,” she said. “Let’s do it in a way that’s consistent with our ideals, so that we can be in for the long haul.”