Mary Ann Mason, Berkeley’s first female graduate dean, gender equity trailblazer, dies at 76

She broke down barriers for women in academia who struggled to balance career and family

August 19, 2020

Mary Ann Mason, former UC Berkeley graduate dean and professor emerita of social welfare, has died at age 76. (Photo courtesy of UC Berkeley)

Mary Ann Mason, UC Berkeley’s first female graduate dean and a dynamic champion for gender equity and work-family balance in academia, died of pancreatic cancer at her home in San Francisco on July 27. She was 76.

Widely admired for her warmth, intellect, elegance and steely determination, Mason advocated steadfastly throughout her career for families and for women breaking into male-dominated professions.

In more than a dozen books, including The Equality Trap, Mothers on the Fast Track, and Do Babies Matter? Mason and her co-authors examined the obstacles keeping women from being competitive in many professions, and sought to remove them.

Mason is awarded the Berkeley Citation in 2007 by Chancellor Robert Birgeneau. (UC Berkeley photo by Cathy Cockrell)

“At a time when women in academia were struggling to balance career and family, Mary Ann Mason broke down barriers to gender equality and made it easier for women to excel in all areas of their lives,” said UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ.

“She approached her mission with empathy, thoughtfulness and solid, well-researched data. Her legacy is extraordinary, and she will be sorely missed by all of us who were her colleagues and friends, as well as the generations of women and men she mentored,” Christ added.

During Mason’s distinguished two decades at UC Berkeley, she served as a professor of social welfare before ascending in 2000 to dean of the campus’s Graduate Division, which serves some 10,000 students. While gathering data about graduate students, she discovered that, while half were female, women represented a much smaller percentage of Berkeley’s tenure-track faculty.

To narrow the gender gap for new generations, she spearheaded the expansion of family-friendly policies for faculty and graduate students, advocating for paid parental leave, paid maternity leave, teaching relief for new parents, dual-career hiring policies, and more child care facilities.

The result became a national model for gender equity in ladder-track academia and, in 2007, won her the Berkeley Citation, one of the campus’s highest honors, which was presented to her by then-Chancellor Robert Birgeneau. The citation is awarded to those “whose contributions to UC Berkeley go beyond the call of duty and whose achievements exceed the standards of excellence in their fields.”

Mason with daughter Eve in 1980 in Inverness, California. (Courtesy of the Ekman family)

Eve Ekman, Mason’s daughter with acclaimed psychologist Paul Ekman, Mason’s husband of 40 years, described her mother as a caring person, whose iron will was softened by her velvet glove.

“My mother had this ability to be incredibly strong and powerful, but with grace and softness,” said Ekman, a social scientist who leads a design team that integrates wellbeing into Apple products and experiences. “She was a profoundly emotionally intelligent person who made people feel at ease because she genuinely cared about them.”

No regrets

Mason was private about her terminal illness. Just two weeks before her death, she let her daughter share, in an email to friends, that her mother was fading fast, and felt at peace.

Mason with daughter Eve in Angkor Wat, Cambodia in 2010. (Courtesy of the Ekman family)

“My Mom wants you to know how much she loves her life, how fortunate she feels to have gone from a small-town Minnesota girl to her most treasured role as dean of the graduate division,” Eve Ekman wrote. “She loved traveling the world almost as much as working on intellectual endeavors that have changed the very face of how women can exist in academia. She feels no regrets and is grateful to be with her family in this challenging time.”

Neil Gilbert, UC Berkeley’s Milton and Gertrude Chernin Professor of Social Welfare and Social Services and a close friend and colleague of Mason’s, recalls how she lit up a room.

“Smiling and lighthearted, Mary Ann exuded a charismatic magnetism that attracted those around her and enlivened our faculty meetings,” he said. “Beyond a delightful colleague, she was that exceptional breed of activist-scholar whose intellectual and policy achievements are a magnificent bequest to our community and an inspiration to those who follow.”

Andrew Scharlach, a professor emeritus of social welfare who arrived at UC Berkeley in 1990, a year after Mason did, was impressed with how quickly she established herself as a respected scholar and teacher of child welfare policy and women’s rights.

“I have always admired Mary Ann’s commitment to reducing the barriers that undermine the academic success of women and persons of color, whether on campus or nationally, as well as her ability to utilize a wide array of scholarly tools to achieve more equitable social policies on behalf of women and their families,” he said. “I will miss her.”

Small-town Minnesota

Mason was born on Aug. 31, 1943, in the iron mining town of Hibbing, Minnesota, the only child of Tom Mason, an immigration officer, and his wife Mary, a homemaker.

Despite her parents insisting that college was for “fancy girls,” she excelled academically from an early age, winning the state title of Whiz Kid Champion for her high scholarly scores, Eve Ekman said.

A teacher encouraged Mason to apply to Vassar College, where she earned a bachelor’s degree cum laude in history in 1965 and made lifelong friends. She went on to study for a Ph.D. in American history at the University of Rochester in New York, where she met and married scientist Jack Burkey. They had a son, Tom.

When Burkey received a research appointment at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory at UC Berkeley, the family moved out west. Mason “never looked back,” Eve Ekman said.

But even with a Ph.D., Mason had trouble landing a job, so she pursued a Juris Doctor from the University of San Francisco and started practicing family law, taking Tom with her to classes in a baby carrier backpack.

In the late 1970s, following a divorce and then death of her ex-husband, she met psychologist Paul Ekman at a party. “They became an incredible power couple,” Eve Ekman said. “Their love story wasn’t always easy, but they had an enduring bond.”

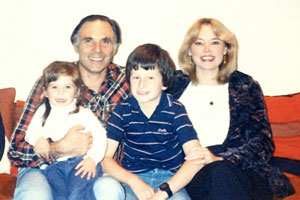

Mason, with Paul Ekman and children Tom and Eve in the 1980s (Courtesy of the Ekman family)

Paul Ekman adopted Tom and they had a daughter, Eve. While raising her two children, Mason practiced law, ran a paralegal program at St. Mary’s College in Moraga and taught courses at various educational institutions.

Eve Ekman recalls an idyllic childhood of travel to exotic research locations and local outdoor adventures. “I grew up witnessing and then following in the footsteps of my parents, who were deeply involved in academic pursuits focused on the greater good,” she said.

In 1988, Mason published The Equality Trap, a book that showed that despite the feminist revolution, the vast majority of women were still stuck in low-paying jobs.

A year later, she joined the UC Berkeley faculty as an assistant professor of social welfare. Over the next decade, she steadily rose through the ranks to become a full professor and, ultimately, dean of the Graduate Division in 2000.

As graduate dean, she combed through data, listened to the experiences of female students and junior faculty, and discovered that women between the ages of 30 and 40 — what she called the “make-or-break years” — struggled to make their professional mark just as the pressure to start a family mounted.

The mommy penalty

With the help of her colleague, Marc Goulden, now UC Berkeley’s director of data initiatives, she gathered more data and sought to diversify academia and to curb discrimination against female graduate students and faculty.

“Mary Ann was a role model to so many women on the Berkeley campus,” said UC Berkeley social welfare professor Jill Duerr Berrick. “She listened to others’ concerns and turned their distress into action, transforming academic policies and practices to be responsive to family demands.”

In the mid-2000s, Mason helped pioneer such cutting-edge programs as the 10-campus UC Faculty Family Friendly Edge. Her research resulted in her 2007 book Mothers on the Fast Track: How a New Generation Can Balance Family and Careers, which she co-authored with her daughter.

In an interview about the book with Berkeley News, Mason openly lamented the systemic biases that prevent mothers from being competitive in many professions.

“If they have the opportunity, mothers go back to work in their 40s, but a lot end up in second-tier jobs. They’re not players anymore. They’ve lost their position in the game,” Mason said.

Mason wasn’t all work and no play, Eve Ekman said. As graduate dean, she noted, her mother co-wrote a crime thriller with her best friend, playwright Lynne Kauffman, called Wild Women’s Weekend.

Mason with the Dalai Lama, and Paul and Eve Ekman in Anaheim, California in 2016. (Courtesy of the Ekman family)

After retiring in 2008, Mason remained active on campus as a Professor of the Graduate School and faculty co-director of UC Berkeley’s Earl Warren Institute on Law and Social Policy.

In 2013, she co-authored Do Babies Matter? Gender and Family in the Ivory Tower, with Goulden and Nicholas Wolfinger, a professor of family and consumer studies at the University of Utah. The book received wide acclaim and coverage in the New York Times and the Atlantic, among other publications.

“To me, our most important finding will always be that women don’t become tenure-track professors because of the differential impact of marriage and kids, not because they’re women. Indeed, single childless women get jobs more often than men,” Wolfinger wrote in a series of tweets, paying tribute to Mason’s life and legacy.

At home in San Francisco (Courtesy of the Ekman family)

In 2017, Mason co-authored Babies of Technology: Assisted Reproduction and the Rights of the Child with her son, Tom Ekman, a science teacher. That same year, she was awarded UC Berkeley’s Edward A. Dickson Emeriti Professorship.

For Duerr Berrick, Mason’s natural ability to empower women is a major part of her legacy.

“Everything about her confidence, intelligence, wit and charm said, ‘I belong here,’ and when she spoke, women knew they belonged here, too,” she said, “She touched the hearts and lives of so many and will be dearly missed.”

In recent years, Mason and Paul Ekman, who lived in San Francisco, enjoyed the theater, eating take-out meals and spending time with family and friends at their place in Inverness, in western Marin County. They were avid birdwatchers.

When Eve Ekman recently asked her mother about the meaning of life, Mason didn’t miss a beat: “To love other people,” she said.

Mason is survived by her husband, Paul Ekman, of San Francisco; daughter, Eve Ekman, of San Francisco; and son, Tom Ekman, of Baja California, Mexico. An online memorial for friends and family is planned for Aug. 31.

SEE ALSO:

Interview with Mary Ann Mason on Conversations with History on UCTV

Mary Ann Mason’s keynote presentation on Do Babies Matter at MoMiCon 2016

Remembering Mary Ann Mason: School of Social Welfare