Objects of resistance: Protesting the feminicide of girls and women at the border

Student reflects on her experiences and the symbols of resistance that make the missing and murdered girls and women of Juárez visible

September 22, 2020

Demonstrators protest feminicide and violence against women on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women in Mexico City, Mexico, on Nov. 25, 2019. UC Berkeley graduate student Laila Espinoza says these magenta crosses, planted all over the city of Ciudad Juárez and across the country, are powerful and enduring symbols of resistance and a way to reclaim public space and make the ongoing feminicides visible, when the government refuses to do so. (Sipa USA photo by Bénédicte Desrus via AP Images)

The first time that Laila Espinoza crossed the U.S.-Mexico border was as a young girl with her grandmother. “I’ve always been a border crosser,” said Espinoza. “It’s who I am.”

Espinoza grew up in Ciudad Juárez, a border city in Chihuahua, Mexico. As a child, she crossed the border hundreds of times — usually with her grandmother, who worked in El Paso cleaning houses. Every time they walked over the Paso del Norte International Bridge, Espinoza would look over the edge at the Rio Grande rushing below. “When I was child, the river was full — it was very, very alive,” said Espinoza.

She’d see entire families crossing the river — men carrying babies on their shoulders and women with bags on their heads. When the tide was low, they’d be walking. But when it was high, they’d have to swim.

“I remember always asking my grandma, ‘How come they can’t cross the way we do?’ And she would always just tell me the same answer: ‘Because they don’t have papers.’

“Papers or not,” said Espinoza today, “we find ways to cross the border — one that has been artificially imposed upon us and has separated families who have lived in the region for generations, before the wall was built.”

A close-up of the huge magenta cross that sits at the entrance of the Paso del Norte International at the Mexico-U.S. border in Ciudad Juárez. Little pieces of paper with names of missing and murdered girls and women are tied to the nails pounded into the cross. (Photo courtesy of Laila Espinoza)

When Espinoza was 13, she was in Juárez, about to cross the bridge with her grandmother, when she stopped. Standing at least 10 feet tall at the entrance of the Paso Del Norte International Bridge was a wooden, magenta cross. Dozens of nails were pounded into the cross, on which little pieces of paper dangled from threads. On each paper was the name of a girl or woman who was missing or had been found murdered in Juárez. “The cross is right at the border,” said Espinoza, “which is just absolutely radical.”

In the months and years that followed, hundreds of magenta crosses began to show up all over Juárez — altars to the growing number of missing and murdered women and girls at the border. The brutal killings would become known as feminicides — a term defined by scholar Marcela Lagarde y de los Rios as gender-based violence characterized by state inaction. Since 1993, some 3,000 girls and women have been reported missing, and more than 600 have been found murdered, in and around Ciudad Juárez, with almost all of the killings going unpunished.

The crosses, along with murals of the missing and murdered girls and women painted on walls throughout the city, are powerful and enduring symbols of resistance, said Espinoza — a way that mothers and families reclaim public space in Ciudad Juárez and make the ongoing feminicides visible, when the government refuses to do so.

“The magenta crosses and the murals of missing and murdered women and girls all over Ciudad Juárez are forms of protest against gender-based violence so prevalent in our culture and so many cultures around the world,” said Espinoza.

Magenta crosses are planted all over Ciudad Juárez and across Mexico, many with names of missing and murdered girls and women written on them. (La Verdad: Periodismo de Investigación photo by Rey R. Jauregui, 2019)

As a graduate student in the performance studies program at UC Berkeley, Espinoza began to recognize other forms of resistance that she had been practicing in everyday rituals — rituals like cooking, singing, dancing and sewing — that she performed with her family in her childhood home, an old lime green house affectionately known as “La Casa Verde.”

“By performing rituals and creating altars inside La Casa Verde — by turning La Casa Verde into an altar itself — we are coming together in resistance inside the home as a way to join the resistance and protest throughout the city,” said Espinoza.

It’s also a way, she said, for them to begin to collectively heal from family tragedies that happened decades before — tragedies that no one ever talked about, no matter how many times she asked.

Performance as social justice

When Espinoza first told her master’s thesis adviser, Angela Marino, about her interest in research and writing about La Casa Verde as a form of resistance to the feminicides in Ciudad Juárez, Marino told her to run with it.

When Laila Espinoza got to Berkeley as a graduate student two years ago, she began to think about the significance of different objects and rituals in her life, and how she could use them to heal from the trauma she experienced growing up. (Photo by Laila Espinoza)

“For Laila, her performance practice is another form of research,” said Marino, a professor in the Department of Theater, Dance and Performance Studies at Berkeley. “It’s a living context that she’s in and that context is still dynamically being made. She’s finding and filling in the blanks that, oftentimes, the official narrative leaves out.”

Marino runs the Teatro Project on campus — a group of students who produce theater and performances on stage and in the streets as a forum for building communal power among Latinx, Black and Indigenous communities in the U.S.

She said that performance is unique in its ability to bring people — both performers and the audience — together in collaboration, creating a space that challenges how people think and feel.

Students in the Teatro Project rehearse on stage. In the Teatro Project, run by professor Angela Marino, students produce theater and performances on stage and in the streets as a forum for building communal power among Latinx, Black and Indigenous communities in the U.S. (Photo courtesy of Angela Marino)

“When people come up with ideas, and they’re creative together, they’re asking themselves, ‘What am I willing to to put into an idea that will be shown? What needs to be said when there is so much talk, and how can we express that in ways that will open a deeper place of understanding and inquiry?’ There’s a commitment it takes. It takes courage — it really takes courage. You have to bring your fullest self to it.

“And then, when people are drawn into a story as a witness, there’s an emotional recognition that’s going on at the same time. It’s a feeling-state that people are brought into that can help them open up a bit and see a perspective that’s different from their own. They’re able to have enough time to sit with it and think and be with both compassion and complexity. And that’s a place of change.”

Students (back to front) Isla Covarrubias, Lulu Matute, Wendy Villalobos and professor Marino (left) paint stage props for a summer production of Teatro, in collaboration with immigrant justice movement organizers Mirna and José Medina. (Photo by Angela Marino)

It’s this space of connection and openness that Espinoza hopes her family will begin to create in their performances of everyday rituals inside of La Casa Verde.

“We perform healing practices of making,” said Espinoza. “We use our bodies. We don’t talk about it much because talking is … I consider it to be a relatively aggressive way of communicating traumatic experiences. Talking should come later, in my belief, and it’s also backed up by my research on indigenous ceremonies of healing. There’s not much talking going on — mostly, just doing things together. When we plant a garden, we are healing ourselves and the earth at the same time.”

For Espinoza, trauma is a familiar feeling — something she has experienced since she was a young child, when one day, her mother was gone.

‘Girls look prettier when they’re quiet’

Espinoza never knew why her mother disappeared — if she left on her own, or if it was out of her control. Growing up, she’d ask about her mother all the time, but never got an answer.

Espinoza’s mother, Laila Feik, disappeared when her daughter was 5 years old. “No one talked about why my mother disappeared,” said Espinoza. “No one wanted to tell me what happened — why she was just there one day, and the next day, she was not.” (Photo courtesy of Laila Espinoza)

“No one talked about why my mother disappeared. No one wanted to tell me what happened — why she was just there one day, and the next day, she was not.

“So much of our culture is that things are just the way they are — that it’s just the way life is. So, I was usually shut down when I asked questions. We have a common saying: Girls look prettier when they’re quiet.”

So, Espinoza turned to her auntie, Maria Del Socorro, for answers. It was her auntie who first told her about the murders in Juárez. “She was sitting at the kitchen table in her house, which was a few houses down from La Casa Verde in the same colonia,” said Espinoza. “And she called us over — me and all of my cousins — and she said, ‘There’s something you need to know.’”

She read them an article in the city’s newspaper, El Diario de Juárez, and didn’t spare the gruesome details. “She read us everything, because she knew that we had to know the truth,” said Espinoza. “After she read the first article to us, she said, ‘This is real. This is happening. And from this day on, none of you are allowed to go outside of your houses by yourself.’”

The victims were young — often teenagers — and had dark skin and long, dark hair. Many of them worked in foreign-owned factories known as maquiladoras, the majority of which are owned by U.S. companies, and were last seen waiting at a bus stop or leaving a factory. Corpses were found, often several at a time, dumped like garbage — in the desert, in fields and in vacant lots. Many of the bodies showed signs of rape, torture and mutiliation.

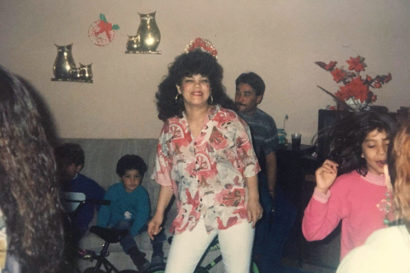

Espinoza’s auntie, Maria Del Socorro, dances at a family event. After Espinoza graduated from high school in the U.S., she learned that her auntie had committed suicide. “I didn’t know what to do,” said Espinoza. “No one would talk about it. I loved her so much. I still do.” (Photo courtesy of Laila Espinoza)

“After I learned about the feminicides, my entire focus shifted to my mother,” said Espinoza. “I became so worried about her. I thought, ‘Where is she? What is happening to her? What if they get to her? What if she is one of them? When am I going to get the bad news?’”

Years later, after Espinoza had graduated from high school in the U.S., she got tragic news from Juárez: Her auntie, Maria Del Socorro — the person who always told her the truth — had committed suicide. “I didn’t know what to do,” said Espinoza. “No one would talk about it. I loved her so much. I still do.”

So, Espinoza did the only thing she knew: She dove deeper into her art and began to work through her pain by creating and making and performing.

Healing in collective resistance

Today, La Casa Verde still stands in Ciudad Juárez — a simple, humble house on a border that has become militarized in a city overrun with drug cartels, where girls and women continue to be abducted and murdered with impunity. The house, with its lime green paint peeling in the hot sun, sits stoically in the middle of what has become one of the most dangerous places in the world.

Espinoza stands next to crosses painted on street posts in Ciudad Juárez. She’s wearing a huipil, a traditional garment worn by Indigenous women from central Mexico to Central America. (Photo by Valeria Puertas)

Through actual and intentional performative and creative practices in the house, said Espinoza, La Casa Verde has become a “disobedient object,” an everyday object that has been given a new purpose — tools of protest used in social movements all over the world.

“Objects have anima,” said Espinoza. “We have relationships with objects. The house has a spirit. The walls are like the skin of the body, and the structure is like the bonds of the body. The house experiences and witnesses everything — trauma, violence, healing — and it’s all absorbed into the walls of the house and in the ground underneath. Therefore, we can use the house as an object of healing, turning it into a type of temple.”

Although Espinoza has yet to find out what happened to her mother, she does know that her mother was a victim of gender-based violence in the home. And when Espinoza sees the magenta crosses throughout Juárez, she thinks of her mother and her auntie — how, even if she might never have answers, it doesn’t stop her from telling her truth and sharing it with others.

As a teenager, Espinoza made a beautiful doll for her auntie as a gift. Years later, Espinoza realized that the doll didn’t look anything like her auntie; it looked exactly like her mother.

“The process of making the doll was part of my healing,” said Espinoza. “My nieces ask me about the doll — about what she represents — and I tell them about my auntie and my mother. I’m the only one who talks about it. I have to do it in secret, because their moms get mad at me when I do, because they think it’s too much for them. But I feel like they need to know. The doll opens up the door to talk about something that no one wants to talk about.”

One of many murals in Ciudad Juárez of missing and murdered women and girls. (Photo courtesy of Laila Espinoza)

When Espinoza, now 40, crosses the border today, she has a mixture of feelings, she said. She feels proud that she and her people remain resilient, no matter how hard the U.S. government tries to demonize them and stop them from crossing the border — something that’s become even harder with tighter restrictions during the coronavirus pandemic.

“We love our families so much that we are willing to put our lives at risk every time we cross the border,” she said. “Even when you do have papers, you never know when something is going to go down. There are militarized police everywhere, and they are very reactionary.”

Espinoza climbs a fence that the City of El Paso put up around the only mural in the city about the feminicides. The neighborhood that the mural is in, Barrio Duranguito, as well as the neighborhood next to it, Segundo Barrio, are the two neighborhoods in the city that are “the oldest, most historic Latino barrios where immigrants live,” said Espinoza. (Photo courtesy of Laila Espinoza)

She also has a heavy heart when she sees how dehumanizing the border has become for so many people over the years, especially since President Trump took office in 2016.

“Two years ago when I crossed, I saw all the campsites at the border in Juárez, where asylum seekers from all over — Central and South America, the Caribbean — were living in tents. Children were living in, not even tents, but tarps and black plastic garbage bags cut flat, stretched and attached to the barbed wire fences that line the perimeter surrounding the spaces between the international bridges.”

She said the worst part has been hearing how members of her own family echo the negative stereotypes that the media repeats about asylum seekers.

“I see how the media has successfully pitted members of the Latin American community against one another, when we are all clearly just trying to survive in a part of a continent that has been sectioned off, exploited and outright depleted for and of its natural and human resources by the countries of the North who consider themselves superior.”

Now, Espinoza is using her experiences living at the border to help others find their own path to self-understanding, and learn that they deserve to heal from trauma.

Teaching others how to heal through art

From her home in El Paso, Texas, where she lives with her 9-year-old son, Nyanga, Espinoza recently started teaching art workshops online — something she loves to do. She hopes, through her art-making and in her workshops, that people will learn that healing is something we all have the power to create for ourselves.

Espinoza and her son, Nyanga, work on art together in their home in El Paso, Texas. (Photo courtesy of Laila Espinoza)

“I want people to know that we have the power to heal from trauma,” she said. “It’s not something to be ashamed of. Mental illness, such as PTSD, which is so common … I want to be able to talk about it openly.

“I also want to be able to talk about our bodies — how we feel about our bodies, how we move in the street with our bodies, how we hide our bodies. I want to be able to talk about the consequences of the feminicides to women who are alive. We also suffer the impact. We also suffer in how we experience ourselves every single day in our bodies, in public.”

Espinoza celebrates her 40th birthday with her family in La Casa Verde. (Photo courtesy of Laila Espinoza)

On International Women’s Day this year, tens of thousands of mothers, families and allies filled the streets of Mexico City in a massive march to protest gender-based violence and inequality. Today, at least 10 women are murdered in Mexico every day, with 90% of the killings going unsolved, making it one of the most dangerous places in the world for girls and women.

Although her family isn’t ready to join the protestors, said Espinoza, she hopes that, someday, they’ll be ready to talk about their collective trauma — what they’ve lived through and continue to live through in a city they love. And, maybe, La Casa Verde, with its all-knowing walls, will help them find their way, one day sending them out into the streets to join in protest.