How compelling photographs can change the course of history

In new book, Berkeley journalism professor compiles ‘Picturing Resistance’ from over six decades of American social movements

October 28, 2020

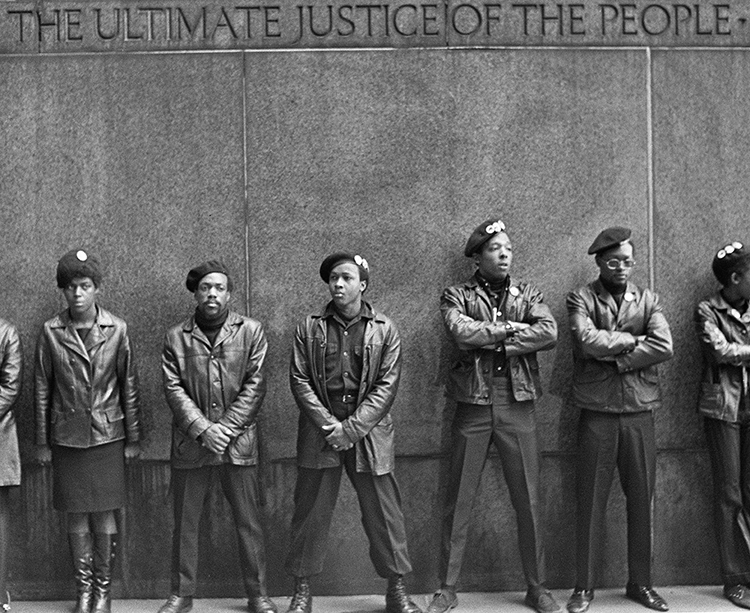

Black Panthers hold a demonstration against the treatment of Black people in the U.S. outside of the Supreme Court of the State of New York in 1970 (Photo by David Fenton)

In the summer of 1955, the murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black teenager who was tortured, shot and thrown in the Tallahatchie River after being accused of flirting with a white woman in Mississippi, brought awareness to the horrific treatment of Black people in America and reignited the civil rights movement.

But for the general public at the time, it wasn’t the callous nature of Till’s murder that struck a chord. It was the funeral images, captured and shared with the world by photographers, of his mother looking over Till’s open casket, listlessly staring at her son’s face, which had been bludgeoned beyond recognition.

Ken Light is the Reva and David Logan Professor of Photojournalism at Berkeley Journalism. (UC Berkeley photo)

UC Berkeley journalism professor Ken Light, an award-winning photojournalist, says moments like that — and the killing of George Floyd earlier this year — “really can change the course of history.”

That is why Light has spent the last two years compiling over 100 iconic images, from 85 photographers and over a span of 65 years, that capture historical moments in America’s social movements. They appear in a new book, Picturing Resistance: Moments and Movements of Social Change from the 1950s to Today, authored by his wife, Melanie Light.

“I really dug into the stories and these movements,” Melanie Light said. “And it’s just all about people like you and me, normal people who step forward and decide to stand up for themselves and others. Something as simple as that can spark a movement.”

Ken Light recently spoke with Berkeley News about his experiences in the field, the changing landscape of media in America and what a photographer’s role is in trying to capture moments of resistance in contemporary social movements.

Berkeley News: There are so many images of resistance and protest throughout history. How did you choose what to include in the book?

Ken Light: It was a challenge to both find photos and also to figure out what events to include. Should we only include major events or look for those moments less seen? An example would be a wonderful photograph from the mid-1960s that we include, of the first woman to run the Boston Marathon.

At the time, they didn’t allow women to run the marathon, and this woman clandestinely pretended she wasn’t a woman. When the race director found out she was a woman, he physically tried to push her out of the race. And there’s a wonderful photograph of that.

(Photo courtesy of Ten Speed Press)

When I think about moments of resistance, I think of these types of moments, as well as those you wouldn’t expect. In this case, this woman just got tired of that rule and was like, ‘Why can’t a woman run in the Boston Marathon?’

So, there are these single moments in time when people just are pushed to the edge, and that sparks resistance and change. And those were the things we were looking for as well.

But there were these much quieter moments that we felt fit into the narrative of what resistance is: It’s also very small and very personal.

There’s a compelling photograph we had of kids opening the fire hydrant in Harlem during the hot summer. Now, some people would say, ‘I don’t know, that’s not resistance.’

But at the time, there were no public pools that these children could go to, living in an underprivileged neighborhood, that no one really cares about them. So, their resistance was opening the fire hydrants in the hot summer.

Resistance really ranged from those ‘power to the people’ moments to those daily interactions that people had that maybe represented things in their life that were not fair.

Some of your photography is in this book. What is a memorable experience you had as a photojournalist?

In the 1970s, I was a student photographer, and I was 19 when demonstrations against the Vietnam war and the Cambodian invasion were happening at universities across the country.

I was photographing these protests at Ohio State University and got arrested.

The National Guard was called out on the campus with bayonets, and they were pushing back against the students protesting and they were firing tear gas at them. Much like you’re seeing today.

Young protesters drive by during a 1969 anti-war event in Washington. (Photo by Ken Light)

All of a sudden, I felt two arms on my shoulders, and a man said, ‘You’re under arrest.’ They took me to a paddy wagon, and I was handcuffed.

And I said, ‘I’m a journalist and I have a press pass on my jacket.’ They ripped it off my jacket and tore it up into little pieces and threw it up in the air like confetti, and said, ‘You’re not a journalist anymore.’

I was charged with inciting to riot, which was three to five years.

When I went to court, at the preliminary hearing, they gave me the option to sign a form that said I wouldn’t press charges for false arrest against them. If I did that, they’d drop the charges.

I turned to my attorney, and I said, ‘I don’t want to sign it.’ My attorney said, ‘The judge is a hanging judge. And you’re in Ohio, I would sign it.’

So, I signed, and they dropped the charges.

Luckily, when I got out of jail, my film was all still there. I then was able to develop the film and sent the pictures to New York, and the photographs were published all over the world.

When you talk about developing film, some photographers no longer use it. The craft of photography has changed over the years. In looking at these photos through a span of 65 years, did you notice any significant changes in the way photos are taken now?

During the earlier eras of the book, there were cultural gatekeepers in the industry, and largely photography was done by white men. So, there were limitations to that, for sure. But the upside is that their work still exists and is in archives or with photo agency’s.

As you move to the end of the book, it was very, very hard to find pictures with that kind of quality as they weren’t as accessible. People now are taking a billion pictures a day, but a lot of them are just photos capturing themselves at a protest — they’re not bringing the historicity to it.

So, it’s a very different landscape.

Facing eviction from Zuccotti Park in New York, NY, thousands of supporters of the Occupy Wall Street movement gathered in lower Manhattan at sunrise for a people’s assembly to determine the next course of action. (Photo by Nina Berman)

Is that a good thing or a bad thing?

It’s just interesting to see how it’s changed. If you were looking at pictures in the 1950s and ‘60s, it was hard to find different points of view.

Now, you have a bazillion points of view. But can you actually find that right picture? I think part of it, from my standpoint, is people are more distracted than they were in earlier generations.

When we didn’t have cell phones and electronic communication, we were fully immersed in the moment. Now, people are going out to protest for the right reason, but they may be very distracted, and they may be more concerned with curating their own moment in that protest.

If you took a picture in 1970 of 500,000 people at an anti-war protest in Washington, D.C., they all had their peace fingers up, or their power fists.

If you took a picture now, they’d all have their cell phones up.

There has also been a tremendous pushback against photographers. It’s to the point where protesters don’t want their pictures taken. They are worried about the police using them, and they are saying, ‘You have no right to curate my world.’

Protesters at Washington Square Park in New York City rally against the Muslim travel ban in 2017. (Photo by Ken Schles)

I think, in earlier eras, there was a sense that we were all in this together, and the photographers served an important purpose of witnessing and recording it.

People understood that. They understood why a photographer was there.

Now, I think, because media has changed, and there’s so much media, people see themselves as their own brand, and their own content creator, and they say ‘Why do we need a photographer there?’

Do you think now, because we are more inundated with videos and social media, that the impact of a photograph has been lost?

With these videos coming out, just think of the George Floyd video. Wow! That just created a whole movement, because people actually saw the cop’s knee on his neck for those eight minutes.

I think the power of the image is even more powerful now. I think the impact is still there.

There are people who are out there who are citizens, and they are witnessing their own world and sharing that world. That has opened up the way that people think about America and what has been happening in America.

And social media has become such a powerful tool for change. The number of images and videos that can be captured really changes how people can record history.

A Marine injured in Fallujah leads a two-mile walk protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline, which cuts across several sacred indigenous sites and tunnels under Lake Oahe, which drains into the Missouri River. (Photo by Alyssa Schukar)

For you, what’s the ultimate goal of this book?

It feels like a lot of the movements have been lost in the history of time, and people don’t necessarily remember them. We are really hoping that this book empowers people to understand that there is a long history in America of political protest that has kept democracy alive and well.

For some people it will be a way to share their own personal experiences with their children and their grandchildren. You know, to be able to say, ‘I was there. I remember battling and protesting the Vietnam War,’ or, ‘I was at that march. Your grandfather was a civil rights activist.’

This book is really the American story. It’s about democracy, and it’s about the nature of democracy.

It’s a living thing.

Since the killing of George Floyd, there’s been a shift, a pivotal moment in America, and we’re hoping that this book brings back the history of American resistance and makes it all alive again.

When people are on the front lines in these movements, they’re together with other people and trying to create a change for the better… You are at your most alive. You are really fulfilling your human potential in such a special and really sacred way.

And we want to remind people how important this is to keep Democracy alive.