Family reckoning: 25 descendants of David Barrows support hall’s unnaming

Raised to be proud of their patriarch, they're also confronting the pain in his legacy.

November 18, 2020

Alec Stewart, a Berkeley Ph.D. student who is David Prescott Barrows’ great-great-grandson, watches the lettering being removed from Barrows Hall on Wednesday. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

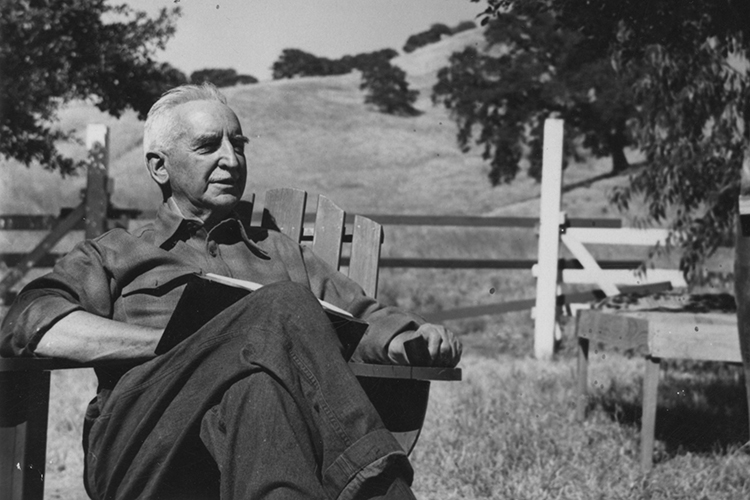

David Prescott Barrows died in 1954, but the former UC president still looms large among his descendants. Known as Grandfather Barrows, Great-Grandfather Barrows, just Barrows, or David, and even Abuelo — “grandfather,” in Spanish, the first language of a few family members — the patriarch set traditions that have lasted nearly a century.

At the Barrows descendants’ annual Christmas Eve celebration in 2019, Colin Bajuniemi, the great-great-great-grandson of David Prescott Barrows, sits atop a Yule log on a sled built by Barrows many decades ago. (Photo courtesy of Lauren Wondolowski)

The yearly Christmas Eve party, begun by Barrows in the 1920s, can draw to the East Bay more than 70 relatives, even from overseas. Precisely two hours long, it starts at 5 p.m., when the newest child, atop a Yule log pulled on a sled that Barrows built, is introduced to the family. The Nativity story is read, carols are sung by the fire and finger sandwiches are consumed.

Sarah Wondolowski Cranford, an educator and Barrows’ great-great-granddaughter, said she and her sister, Dr. Lauren Wondolowski, a physician in Contra Costa County, “have never missed a Christmas Eve in our whole lives. It’s kind of our anchor in maintaining connections with extended family, and our family has big respect for traditions.”

But last summer, as waves of civic unrest over systemic racism swept the U.S., the sisters, their cousin, Alec Stewart, and their uncle, John Cunningham, tested those family ties. Increasingly aware of the troubling side of their ancestor’s legacy, they called a family Zoom meeting to announce their support for a proposal submitted to UC Berkeley in July to unname Barrows Hall; the request was granted today.

David Barrows — professor, anthropologist, military officer and the academic building’s namesake — had “advanced the interests of white supremacy,” stated a group of campus community members in their bid to Chancellor Carol Christ’s Building Name Review Committee.

“Continuing to honor Barrows’ legacy,” the unnaming proposal said, “is especially harmful to Black and Brown students, faculty and staff and undermines the integrity of our university.” The authors cited Barrows’ prominent role in the U.S. colonization of the Philippines during the early 1900s, as well as his “anti-Black, anti-Filipinx, anti-Indigenous, xenophobic and Anglocentric” words and actions.

John Barrows Cunningham, whose middle name is that of his great-grandfather, former UC President David Barrows, signed a letter agreeing that his ancestor’s name should be removed from UC Berkeley’s Barrows Hall. (Photo courtesy of John Cunningham)

Cunningham, Barrows’ great-grandson, a 1983 Berkeley alumnus and executive director of the National AIDS Memorial, said he felt compelled to take a stand, along with the three cousins: “No building is worth causing pain for others.”

“We were raised to be proud of who (Barrows) was,” said Cunningham, whose middle name, and that of a few other relatives, is Barrows. “But this (proposal) unveiled some stuff for us that needed to be looked at. We want to stand on the right side of history, because he was part of a system of oppression that stood on the wrong side of history. It’s a matter of doing right by others.”

Stewart, Barrows’ great-great-grandson, said he and the Wondolowski sisters relied on their Uncle John and his charisma to gather nearly 50 relatives for the Aug. 12 Zoom meeting; 16 families took part. Others emailed their thoughts or weren’t able or willing to attend.

The end result was an Aug. 20 letter to the Building Name Review Committee signed by 25 family members — all from the Bay Area, many of them Berkeley alumni — supporting the proposal to remove the Barrows name and acknowledging the “deep pain” caused by their patriarch’s involvement with the social structures of “white supremacy, systemic racism, colonialism and oppression.”

They also offered, in the letter, “to sit in conversation with those who are directly affected by Barrows’ legacy. We are willing to be vulnerable with you, to learn and grow with you, and to put actions behind our words.”

Another family tradition set by patriarch David Prescott Barrows was spending Easter on a ranch he established in what today is Lafayette. Five acres remain, and a pool there is a gathering spot for dozens of relatives. (Photo courtesy of the Barrows family)

Compelled to take a closer look

That wasn’t the first letter about Barrows Hall that Barrows’ descendants sent to campus. But it’s the one that shows a major shift in thought and purpose over the past few years on the part of more than a few family members.

In April 2016, after Berkeley’s Black Student Union demanded that Barrows Hall lose its name — it was one of 10 demands students made to then-Chancellor Nicholas Dirks to improve the campus climate for Black students — elder members of the family drafted a letter to campus, urging that the name remain.

Stewart, a landscape historian who received his B.A. in geography from Berkeley in 2005 and will get his Berkeley Ph.D. in architecture next month, said the letter listed the names of 20 or so family members who are UC Berkeley alumni, including himself, Cranford and Cunningham.

The family’s 2016 letter, he said, “listed Barrows’ contributions to the University, but did not acknowledge the demands made (by students). It was the wake-up call that started my reexamination of Barrows’ legacy.”

Lettering is removed from Barrows Hall on Wednesday following an announcement by campus officials that both Barrows and LeConte halls had been unnamed. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

Stewart began reading Daily Cal op-eds calling for Barrows Hall to be unnamed, as well as scholarly writings by and about Barrows. He recalled his undergraduate development studies courses and the effects of U.S. imperialism in the Americas and Asia. The Oakland resident contacted former classmates and friends, some from underrepresented groups and former ethnic studies majors, asking them how they’d felt attending classes in Barrows Hall, home of social sciences departments.

“A lot of my contemporaries thought it was sort of messed up, that the building was named after Barrows,” he said. “I’d also found a speech he’d given at the Commonwealth Club, where he spoke on the issue of Philippine immigration in the ‘30s, and he spoke out against miscegenation, and that did it for me. My wife is not white.”

Cranford, a 2005 Berkeley graduate who lives in San Ramon, also was struggling with Barrows’ legacy. “Reading Barrows’ writings that refer to the Filipinx population as ‘savages’ and call for implementing a system of colonial education, to civilize them, I thought it was time to take a stand,” she said. “Students were feeling personally attacked by the name.”

When she was on campus, as a fifth-generation Berkeley student and a political science major who was often in Barrows Hall, Cranford said she “felt an immediate sense of comfort, because the Barrows name was on the building. That was my name up there. I felt and I knew I belonged.”

Alec Stewart, along with two cousins — Sarah Wondolowski Cranford and Lauren Wondolowski — and their uncle, John Cunningham, organized a family Zoom meeting to discuss why the foursome was sending a letter to Berkeley in support of a proposal to unname Barrows Hall. Ultimately, 21 other relatives added their signatures. (Photo by Angela Kim)

David Barrows taught political science and was dean of the Department of Political Science during his career. Barrows Hall, that department’s headquarters, still houses some of Barrows’ belongings, from his former office, and a bust of him sits near the stairwell.

“Ultimately, for me,” said Cranford, “it comes down to how people feel today when they walk into that building. Those are the students, many of them first-generation college students, who need to feel that sense of belonging, not me.”

In 2017, David Barrows’ great-great-great-grandson, Nicholas, took his turn on the Yule log next to his mother, Sarah Cranford, who also is one of Barrows’ descendants. (Photo courtesy of Sarah Cranford)

A surprising ‘avalanche’ of support

Cranford said she, her sister and Stewart originally had planned to write a letter on their own in support of the unnaming proposal and to simply let the rest of the family know about it via the Zoom meeting.

“We thought, ‘OK, it’ll be an hour, and then we’ll end the call.’ We were very prepared in what we were going to say. We didn’t have our letter written, at that point. But when we talked about our privilege, and our own journeys, and how we’d become aware of our place in the systemic racism that exists in the world, one by one an avalanche of them said, ‘I agree. This could be the time’” to unname the hall.

Cunningham described the virtual get-together as “a very painful, very healthy conversation. It pulled the veil back. People had never really seen or looked at (David) Barrows through that lens. There was great openness and compassion and understanding — our family, for the most part, is progressive and humanist in their ways.”

Stewart said that, as the meeting’s leaders, “we were pleasantly shocked, surprised, that we even got 16 people to show up. Many of them grew up in the Bay Area and had an intimate relationship with the idea of Grandfather Barrows.”

He had emailed the invitees some articles about David Barrows, as well as the unnaming proposal, and then circulated as a Google doc the letter that he and his two cousins put together.

“A little over half signed,” he said. “Not everyone responded.”

At the family’s yearly Christmas Eve celebration in 1935, patriarch David Barrows and his wife, Anna, are surrounded by many of their grandchildren. (Photo courtesy of the Barrows family)

But the meeting was successful enough that Stewart said he, his two cousins and his uncle would like to “challenge other families to have a conversation similar to the one we had. We’ve found ourselves in the middle of a debate, at a historical moment in our nation, where we believe that introspection into painful family legacies is being demanded.”

Cunningham said the nation’s racial crisis “demands that individuals look inward and seek to better understand the role of white privilege in our society. Family units, too, are called upon to do the same. This is how we grow and evolve and become better members of society.”

He added that he and other relatives also hope to be in conversation with Berkeley students, staff and faculty — “as human beings, members of society trying to grow. It’s a matter of listening. The biggest thing we can do is listen.”

This Christmas Eve, the Barrows’ descendants yearly party won’t be held in person, because of the coronavirus pandemic. But Cranford said the family will still keep the tradition her great-great-grandfather began — and start something new.

“We’re going to gather on Zoom,” she said. “My baby is the youngest one this year, and I might pop him on the Yule log at my Aunt Julie’s house, and then have a breakout session to read the Christmas story, do Christmas carols, and to keep talking about David Barrows’ legacy. We might have the highest turnout yet.”