Documentarian hopes film on Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 is wake-up call

Eric Stover, faculty director of the Human Rights Center, sheds light in upcoming PBS documentary on the hidden racist rampage in which Black residents were slaughtered, their thriving community torched

November 23, 2020

Eric Stover peers into Oaklawn Cemetery in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where a mass grave was discovered this fall in the search for the remains of Black residents killed in the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. Community members had woven bouquets of flowers into the fencing. (Saybrook Productions image)

Eric Stover, faculty director of UC Berkeley’s Human Rights Center, has investigated war crimes and human rights abuses for more than 40 years. He has led forensic investigations of mass graves in Argentina, Guatemala, Honduras, Brazil, Iraq, El Salvador, Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia. Stover is a founding member of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, which was a co-recipient in 1997 of the Nobel Peace Prize, and has researched human trafficking in California. In Northern Uganda, with the MacArthur Foundation, he helped establish the Pader Girls Academy, for young victims of the Lord’s Resistance Army.

Currently, Stover is working on a PBS documentary about the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. It will air in May 2021, on the centennial of what’s known as one of the worst incidents in American history of racial violence against Black people. Stover traveled to Oklahoma before and during the coronavirus pandemic to interview scientists and activists now searching in Tulsa for mass graves.

Stover has published 10 books. His latest, published last month, is “Silent Witness: Forensic DNA Evidence in Criminal Investigations and Humanitarian Disasters,” which he co-edited with Henry Erlich and Thomas J. White. It tracks the scientific advances of DNA analysis and how they have affected criminal and social justice. He has also co-produced several documentaries, including, in 2016, “Dead Reckoning,” a three-part series for PBS, with Jonathan Silvers of Saybrook Productions. It examines the pursuit — and lack — of justice after wartime atrocities.

Berkeley News recently spoke with Stover about the Tulsa documentary, current efforts to find remains of those killed and the importance of not forgetting history.

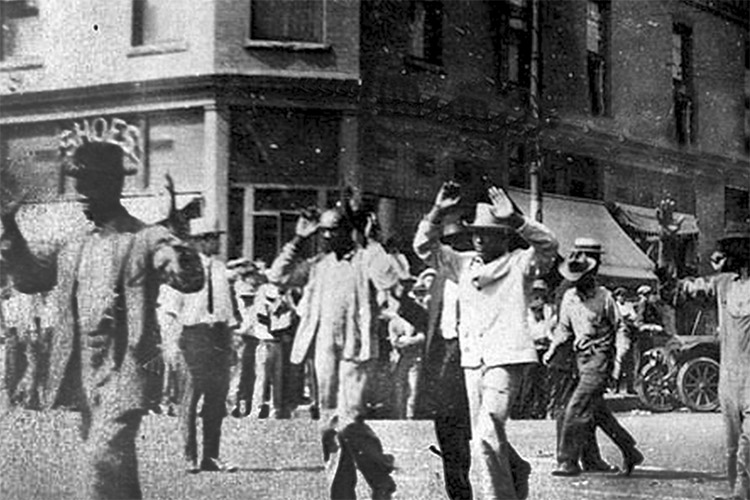

A rampage by a white mob that began May 31, 1921, in a prosperous area of Tulsa, Oklahoma, known as Black Wall Street, left more than 100 Black people dead, 37 blocks of their homes and businesses burned and thousands of residents homeless. (Library of Congress/Wikipedia)

Berkeley News: You’ve titled the documentary ‘The Fire and the Forgotten.’ Why? And what is your goal, with this film?

Eric Stover: Our hope is that this film will contribute to the struggle for racial justice by going back to the future. In the early 1900s, Tulsa was an incredibly prosperous city. It surged with oil money, and Tulsa’s Black residents had built one of the wealthiest Black communities in the United States. But Tulsa was a very racist city. The Ku Klux Klan was active, segregation was the order of the day and lynchings were common throughout the state.

The race massacre took place on Memorial Day weekend of 1921, when Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black teenager, walked into the Drexel Building, which had the only toilet available to Black people in downtown Tulsa. Shortly after he stepped into the elevator, Sarah Page, the white elevator operator, shrieked. No one knows what exactly happened. But the most common explanation is that Rowland accidentally stepped on her foot. He was arrested and taken to a Tulsa courthouse, as a white mob gathered outside. A group of Black men, some just back from the war, arrived to defend Rowland. A struggle ensued, and a shot was fired.

White residents, many of them deputized and given weapons by city officials, embarked on a three-day rampage, killing more than 100 Black residents and setting fires to hundreds of Black-owned businesses and homes in a district so prosperous Booker T. Washington dubbed it “the Negro Wall Street.” The violence left thousands of Black people homeless and 37 blocks of homes and businesses smoldering.

During the massacre, the National Guard imprisoned Black Tulsans, but not the white rioters, and more than 6,000 Black people were interned on the Tulsa fairgrounds, some for as long as eight days. (McFarlain Library, University of Tulsa)

Then, there was silence. Hence, “the forgotten” in the title of our documentary. No one was punished for the race massacre. School textbooks made no reference of these crimes. It was discussed in Tulsa, but only behind closed doors in hushed conversations. When the press mentioned the violence, it was characterized as a ‘riot,’ and not as a massacre.

Our hope is that the film, like today’s protests, will be a wake-up call, although much too late, for all of us to work together to end racial violence in this country and to understand how it has been passed down through generations. We want viewers to see what Black and white Tulsans — whether activists, politicians, or library archivists — are doing today to honor the race massacre victims and to end racism in their city. And we are looking to the future through the eyes of young Black entrepreneurs like Tyrance Billingsley, who founded Black Tech Street, a nonprofit aimed at providing young Black people in the tech world with training and job opportunities to keep them in Tulsa to build careers and revitalize the community.

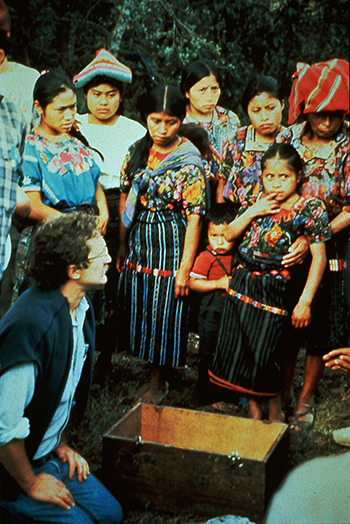

Eric Stover’s colleague and prominent forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow, who died in 2014, did the early work in Tulsa to uncover mortuary and cemetery records and to use ground-penetrating radar to search for remains of victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. (Photo by Eric Stover)

Clyde Snow, an internationally-renowned forensic anthropologist who died in 2014 at age 86 and was your friend and longtime colleague, inspired you to produce the film. How so?

I first met Clyde Snow in the mid-1980s, when I asked him to travel with me to Argentina to advise the new civilian government on how to investigate the fate of thousands of people killed by the military and buried in unmarked graves. He and I later assembled a team of Argentine medical and archeology students to carry out this work. Together, with the Argentine team, we helped establish similar teams throughout Central and South America. The objectives were threefold: to identify the victims, so their remains could be returned to family members for proper burial, to use this evidence to convict the perpetrators and to establish a historical record. Now, more than 30 years later, the Argentine and Guatemala teams are still hard at work. Meanwhile, Snow and I went on to also conduct forensic investigations of the Bosnia and Rwanda genocides for international courts.

One day, in 1997, Snow, who lived in Norman, Oklahoma, called me at my home in Berkeley. He was in a hotel room in Tulsa and had just been appointed to a commission set up by the Oklahoma Legislature to investigate the whereabouts of the mass graves associated with the Tulsa race massacre. He insisted I join him. But I couldn’t, because of my teaching schedule.

Snow put his heart and soul into the investigation. He uncovered mortuary and cemetery records and used ground-penetrating radar to discover anomalies in the city’s Oaklawn Cemetery, suggesting there were mass graves dating back to the early 1920s. In its final report, the commission recommended that the city excavate the site and recommended reparations to survivors and descendants of survivors. But nothing happened. Snow was deeply upset — after all, this had happened in his own backward.

The documentary is told through the stories of people connected to the massacre and its grim legacy, including journalist DeNeen Brown. She was born in Oklahoma, her father lives in Tulsa, and she’s been reporting on the history of the massacre, which will reach Its 100th anniversary in May. Here, she’s looking out over the Arkansas River, where bodies may have been thrown after the massacre. The city is investigating an area along the river called The Canes. (Saybrook Productions image)

Enter DeNeen Brown, an award-winning African American reporter at The Washington Post who was born in Oklahoma. In the fall of 2018, Brown went to Tulsa to visit her father, a Baptist preacher. He took her to Black Wall Street, and she saw plaques embedded in the sidewalks indicating where black businesses and homes had been destroyed during the race massacre. She wondered about the development and gentrification on the site of a massacre and also — with the centennial of the massacre fast approaching — what the city was doing to investigate the killings and memorialize the victims.

When she returned to Washington, her editor recognized that the development on Black Wall Street was a good story and sent her back to Tulsa to report on it. Her story appeared on the front page of The Post in September 2018. A day later, the city’s mayor, G.T. Bynum, announced he would reopen the investigation, and as a murder investigation. Bynum established the 1921 Race Massacre Burial Sites Oversight Committee to examine the massacre, including sites Snow had discovered nearly 20 years earlier. Several scientists on the team are people of African descent, including Phoebe Stubblefield, a forensic anthropologist and former director of the Forensic Science Program at University of North Dakota, and Lesley Rankin-Hill, an associate professor emerita of anthropology at the University of Oklahoma who had studied under Snow. Rankin-Hill went on to uncover Black burial grounds of freed slaves from the late 1800s, including in Philadelphia.

When Jonathan Silvers heard of the mayor’s announcement, he asked if I would join him in making a documentary. I said, ‘Of course.’ Brown joined us, and we began filming in October 2019.

In October, a team of archeologists and forensic anthropologists unearthed 12 coffins — 11 in a trench and another nearby — in a city cemetery in Tulsa, Oklahoma, while searching for victims of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Funerals were not allowed for these victims, and the burials were unrecorded and happened quickly. (Photo by Eric Stover)

You traveled to Tulsa this fall to film. What did you observe, and were you allowed to film the discovery of the graves?

Last July, the scientific team cut a trench across one of the sites in Oaklawn Cemetery that Snow had identified years ago, but found nothing. In October, the team moved to another site at the cemetery. This time, they discovered 11 coffins buried in a trench and another one nearby. We filmed the investigation, but at a distance. Then cold weather hit, and the investigation was closed down. But this discovery was very significant, and the configuration of the trench suggests that many more individuals may be buried there. But we will have to wait until next March or April, when the investigation resumes, to learn more.

One might ask: What is the purpose of an investigation of a massacre that took place nearly 100 years later? But that’s exactly the point: No murder should ever go uninvestigated, no matter how many years have passed. The investigation isn’t about counting the numbers of dead or of revealing what happened. We may never know how many died, and we already know what happened. It is about commemorating those who perished and ensuring that they are never forgotten, as they were for so many decades.

It also is about recognizing and honoring the dead. Because of systemic racism in our country, African Americans, similar to Native Americans, have been the invisible people in the historical record. After the massacre happened, no attempt was made by city or state officials to record all the deaths — let alone identify the dead. Since family members were being held in internment camps, they couldn’t come forward to identify the dead. So, what happens? The bodies of the deceased were either buried in the Black paupers’ section of cemeteries or dumped in the Arkansas River. And now their stories must be told.

Using ground-penetrating radar, an archaeologist at Oaklawn Cemetery in Tulsa last October scans deep in the soil for evidence of abnormalities that could mean human remains are below. (Saybrook Productions image)

Since the massacre happened nearly 100 years ago, if bodies are found, can they be identified, and how? Can descendants be found?

Identifying the dead, if they are found, will be very challenging. It is possible certain objects, such as keys or even rings or belt buckles, could provide the forensic scientists with certain clues. But the only real tool will be forensic DNA analysis. DNA could be extracted from teeth and the skeletal remains to create a genetic profile, but given the passage of time, it will be very difficult tracking down living descendants, securing DNA samples and trying to find a profile that indicates a relationship. Another approach might be to enter DNA profiles from the remains into genealogical databases, like Ancestory.com or 23andMe and search for partial matches to those of relatives. Lastly, Black residents in Tulsa could provide DNA samples for comparison. However, after the massacre, many Blacks residents, having lost their homes and businesses, fled the city. That said, every effort should be made to identify the deceased. And, if it happens even in one case, it will be remarkable.

Eric Stover at the first exhumation of a mass grave in Guatemala in the early 1990s. It was next to a village near Chichicastenango and believed to contain the remains of villagers who had been executed by the military. He is asking permission, from family members who believe the grave contains their loved ones, to remove the remains so they can be taken to a hospital to be examined. (Photo credit: Pamela Blotner)

You’ve been all over the world, where horrific things have happened, looking for truth. What drives you to do this work?

It is a privilege. We do it for the families of the disappeared who are often living in a limbo world of hope and denial and want nothing more than to find their loved ones, so that they can give them a proper burial and seek justice. I can’t tell you how many times a family member of a victim would be at an exhumation site and ask one of the Argentine or Guatemalan team members to come to their house for coffee or dinner. These interactions give great meaning to the investigators. They also enable the investigtors to inquire if family members can provide DNA samples or even have pre-mortem X-rays of the teeth or bone fractures of the deceased, which can help to identify victims. At the end of the day, family members are helping the investigators fulfill their mission and cope with what is very emotionally trying work, while the investigators are giving the family members something deeply meaningful in return.