COVID Stories: Restoring a 17th century manor in Spain

Ph.D. candidate in architecture, stranded abroad during pandemic, finds joy and mends sorrow with the project of a lifetime

February 8, 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic has separated us, but sharing stories about how members of the campus community have been surviving — and even thriving — since last spring can help draw us together. Berkeley News is gathering inspiring personal tales of heartache and triumph related to the coronavirus and will run them periodically in the coming weeks. If you’d like to pitch us your story, send a brief email to [email protected].

This is the fourth story in the series. It highlights Alberto Sanchez-Sanchez, a Ph.D. candidate in architecture at the College of Environmental Design.

My dad’s family has lived in the Spanish village of Used — pronounced “Ooo-sedth” in English — for generations, at least since the late 1700s. My mom’s family comes from the Basque Country and Andalusia. My parents met in Madrid in the 1970s, and it was love at first sight. Right after getting married, they decided to leave the city behind and move to the countryside, to my dad’s hometown — Used, province of Zaragoza — where they raised us all; I have three brothers. Two of my dad’s siblings also live in the town — my aunt Manolita and my uncle Aurelio.

I remember being interested in the built environment since I was a kid. Growing up in Used, I could see the effects of rural depopulation firsthand. I saw all these abandoned, derelict houses no one seemed to care about. Today, there are merely 250 people living in the town, a 90% decrease since 1950, and depopulation continues.

Used had been a major stop in the route between Madrid and Barcelona until the 19th century, and it has several manors that bear witness to that importance. When the road between Madrid and Barcelona was rerouted in the 1830s, Used started to decline, and things only accelerated in the 20th century. It was my early fascination with the effects of depopulation on Used’s built environment that took me at age 17 to the Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, where I obtained a professional degree in architecture in 2012.

I came to the U.S. in 2014 on a Fulbright scholarship and got my second master’s degree, in historic preservation, at Columbia University in 2016. After graduating, I worked for a year at the World Monuments Fund, in the Empire State Building, while applying to doctoral programs. Right after being admitted to UC Berkeley, the house I always loved in my tiny hometown was put up for sale. My brother Ricardo spotted it online and sent me the ad. Even as a kid, I remember taking pictures of it with my very first digital camera.

A few weeks later, I was flying to Spain to my brother Alejandro’s wedding. I arrived in Spain on Thursday, visited the house on Friday, attended the wedding on Saturday and returned to NYC on Sunday. After two months negotiating with the real estate broker, I bought the house in June 2017, with my life savings, a few months before starting my Ph.D. in architecture at Berkeley. You could say it was a fit of romanticism.

Fast forward to 2019, after two and a half years at Berkeley, and I returned to Spain to conduct archival research and fieldwork for my dissertation. I decided to move back to my tiny hometown while I looked for an apartment in Madrid, because the archives I need to use for my dissertation are there. Then, the pandemic hit, the Spanish government announced a strict lockdown, and I found myself stranded in Used. And then, I was like, “Oh, this is my chance to actually do some work on the house!”

I decided to stay in Used by myself, at my parents’ house. My dad is retired, and my mother works in Zaragoza, so they chose to stay in that city together. I had my meals with my aunt and uncle, who live across the street. That way, I could keep them company. I could not live in the house I bought, because it has no electricity and no running water!

But my house has been an anchor that has helped me deal with some difficult moments, including the passing in March of my grandmother, Carmen, in Madrid, due to COVID-19. In early March, days before the beginning of the lockdown, she was hospitalized because she was suffering severe gut pain. We feared she would eventually catch COVID, and that is exactly what happened. She passed away on March 24, just a few days after she had tested positive. My uncle Ramón broke protocol to hold her hand while she passed away.

The following weeks were truly awful: The number of COVID-related deaths was so high that the Madrid regional government kept moving corpses from one morgue to another — at some point we weren’t even sure about my grandmother’s whereabouts — and we could not bury her until weeks later. None of my uncles or aunts could even give a hug to my grandfather, Pepe, who is 88 years old and at high risk of getting the virus. There was no funeral, and only three people were allowed to attend a brief service during the burial.

It was very sad, because my grandmother was truly a people person. She was the most talkative, high-spirited woman I have ever met. She was a radio pioneer in her Basque hometown of Eibar, and she was also a music lover and a musician. During World War II, her parents hosted three Jewish refugees at their home, and one of them — an orchestra conductor — taught her to play piano. Like her parents, she was generous and concerned with social justice. She was also a devout Catholic who spent some three hours a day praying.

The last time I saw her was in early January 2020, when I was invited by a sintered stone company to give a talk in Madrid on the restoration of my manor. I almost declined the invitation, but for some reason I said yes. I am so glad I did. I spent a couple days in Madrid and was able to spend time with my grandparents. In a way, the house helped me see my grandmother one last time.

When you approach Used coming from Zaragoza, the house, which occupies a trapezoidal plot of some 7,500 square feet, is the first building you see, and it has always occupied that prominent location. The property actually is a cluster of buildings that includes the main house, granaries, stables, a farmyard and a garden. It is considered the ancestral home of the lower-nobility Ibáñez de Bernabé lineage, which started in the 1650s. However, I found a document from 1507 at the house that talked about the Ibáñez family already living in Used in the early 1500s. The house was kept by descendants of different branches of the Ibáñez de Bernabé lineage until I bought it.

Most of what I know about the lineage comes from historical records I found at the house and from secondary sources that I have been able to consult. The first documented Ibáñez was a royal notary to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. One of the women who lived at the house was a lady-in-waiting to Queen Mariana of Austria. There were also many Ibáñez family members who served the Catholic Church. For generations, the family was deeply Catholic, very pious, and commissioned religious paintings, sculptures and altarpieces for the house and the local church.

The last family at the house was the Sanz Vicente family. Dr. Pedro Sanz was the town’s doctor, and he married Pilar Vicente, who descended from the Ibáñez de Bernabé family. They lived in town until the doctor retired in 1965. Their youngest daughter inherited the house and fought hard to keep it, rejecting purchase offers for decades. When one of the side facades collapsed in 2016, she realized she needed to sell. She is an 80-year-old retired doctor, with no kids, and none of her nephews and nieces wanted the house. I promised her I would cherish it: I am architect and preservationist, and I am from the town. She had done her research on who I was: When we first met, she opened a folder where she’d put copies of all the articles that I had published about Used’s heritage!

Until 2020, I had not been able to spend more than a few consecutive weeks working at the house, as I was living in the U.S. But stranded in Used, I have managed to measure the entire house, and I am currently completing the blueprints and the rehabilitation master plan I hope to implement during the next 10 to 15 years or so. I have also 360-degree-photographed the entire house, and I laser scanned the first floor.

When you buy a historic house, you really don’t know what you are getting. There might be negative surprises. The roof of the house I bought was in terrible condition, the electrical wiring was obsolete, and there was no plumbing at all. The granaries had collapsed, making it almost impossible to enter the so-called “room of books,” a little chamber where Dr. Pedro Sanz had a little library. I think I am quite handy, and my dad is helping me a lot with the rehabilitation, but there are many things I will need professional help with.

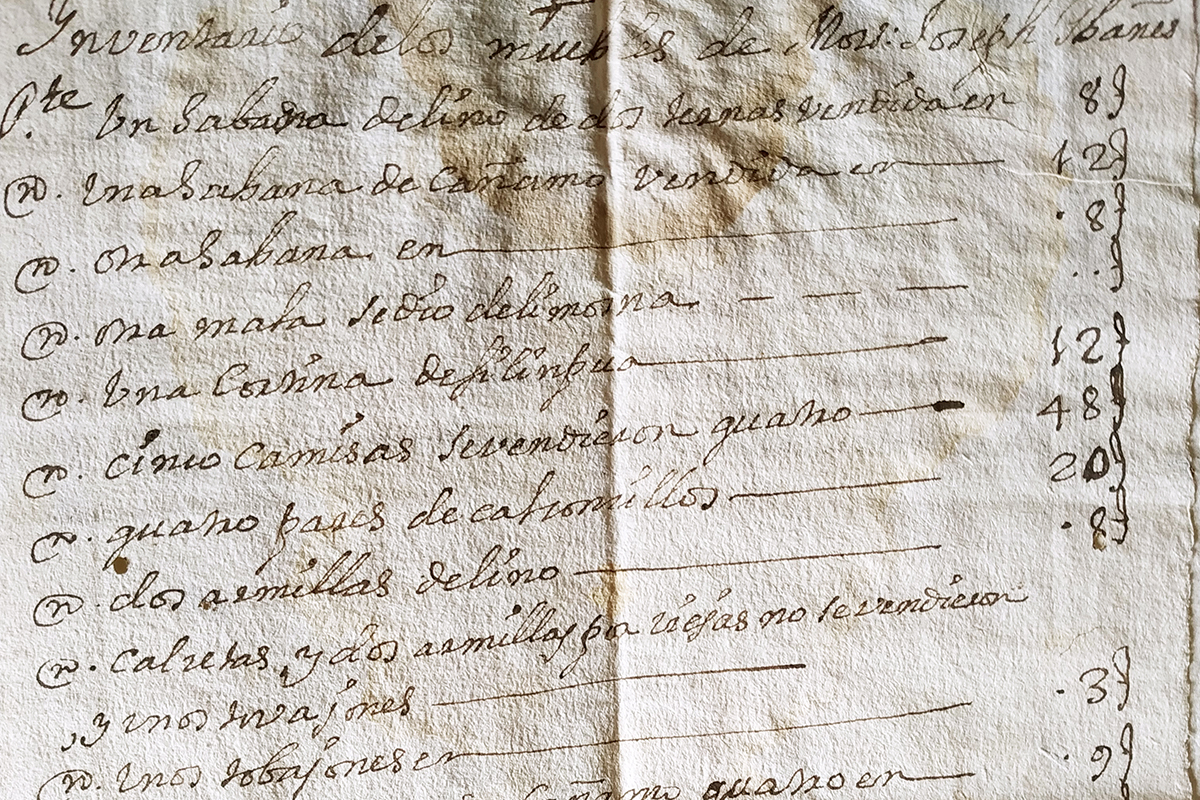

And there might be positive surprises, too, For example, never in a million years would I have imagined finding a collection of 400 or so historic documents dating from the 1500s to the late 19th century.

While water, insects and rodents had taken a toll on many of the records, most were in surprisingly good condition. I found all kinds of things, from a letter to King Charles II of Spain to a 1695 marriage contract and a butcher’s receipt from the 1700s. There were plans for construction work done at the house over the last four centuries, inventories of furniture and clothing, marriage contracts, papal bulls and poems written by some of the house’s inhabitants throughout history. I have been fortunate to receive the support of Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design Joan E. Draper Architectural History Research Endowment to restore and digitize these documents, and I hope they will be publicly available by the end of 2021.

The other mind-blowing discovery I made was 20 or so Baroque paintings in the attic. They were in a terrible condition, many of them apparently beyond repair. Fortunately, I have been able to sign agreements and collaborate with two Spanish art conservation schools — Escuela Superior de Conservación y Restauración de Bienes Culturales de Madrid and Escuela Superior de Conservación y Restauración de Bienes culturales de Aragón — to get some of them restored. I was so thankful and happy to see the painting of Saint John the Baptist one year later. Look what was behind decades of dust!

Since 2017, I have documented my work at the house in my Instagram account, casadepueblo. In 2020, I reached 10K followers, and I presented the impact that sharing my work on Instagram has had on the project during the biennial congress of the International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Work. The Instagram conversations among all the agents involved and interested in the project —myself, students and professors at the two art conservation schools, professional conservators, collectors, art conservation students and art aficionados— have fostered the creation of a commons of conservation knowledge on Instagram, where teaching, learning, and research are exchanged for the benefit of all the participants in these discussions.

I am now working on the drawings I have to submit to the town’s council and to the state agency responsible for historic preservation to rehabilitate the 1690 granaries, which I hope to do over 2021. The granaries at my house are one of the very few examples of this building type that still exists in Aragon. It is an elevated structure meant to store wheat, which was used to feed the family and to sell. Manor houses in cereal-producing areas used to have them, but most of them have already been demolished.

One of the reasons why I bought the house in 2017 was that, after three years living in the U.S. and just months before starting my Ph.D., I wanted to strengthen my roots in Used. Now, four years later, and after six years living in the U.S., I am happy to say that I do feel the house has helped me stay connected to who I am and where I come from. Of course, I would have visited Used often, if only to see my family. But the house gives me that additional reason to come.

Once I finish my Ph.D., I may stay in the U.S., if I find an interesting job opportunity. I may also return to Europe. I may move back to Spain, live at the house and work remotely. If there is something that I have learned from this past year, it is that no one knows what the future holds!

For now, I just want the rehabilitation of the manor to be a project in itself. I want to bring architecture and preservation students to the house. I want to organize summer workshops on traditional building techniques. I want to host multidisciplinary seminars on sustainable architecture and preservation. I really want this house to be the source of multiple initiatives related to architecture, preservation and sustainability that help fight rural depopulation. My dissertation is quite related to the work I am doing at the manor, since I am studying rural-to-urban migration in Spain during the 1960s, when the property was left vacant.

I was recently re-reading this wonderful book, Curated Decay: Heritage Beyond Saving by Caitlin DeSilvey. She says that “conservation of the material past, in its most familiar mode, is an act of ‘self-preservation,’ an impulse that seeks to maintain the relation between self and surround.”

Restoring the house is the activity that is helping me stay grounded during these difficult months. While I wait for the lockdown to end, and my move to conduct archival research for my dissertation, restoring the manor is the activity that is keeping me busy, bringing me joy and helping me stay grounded during these difficult times.