The old guard and Trumpism are at war. Can the GOP survive?

Impeachment puts the GOP itself on trial, Berkeley scholars say

February 12, 2021

In the aftermath of the violent attack on the Capitol and a second impeachment trial, the future of the Republican Party is likely to be fought out by such figures as Sen. Mitch McConnell, former President Donald Trump, and new Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, a past advocate of the QAnon conspiracy movement. (Image by Hulda Nelson)

After furious attempts to overturn his loss in the November election, after a campaign of conspiracy theories and a right-wing mob assault on the U.S. Capitol that left five people dead and hundreds injured, former President Donald Trump is on trial in the U.S. Senate, impeached for inciting insurrection. But as the world watches this historic spectacle of democracy and its discontents, Trump’s Republican Party is on trial, too.

Thomas Mann

For more than four years, most elected Republican officials and other party leaders have stood behind Trump through a near-continuous shattering of political norms and traditions, and tens of millions of voters have followed, almost in lockstep. Now, UC Berkeley scholars say, the party has come to a juncture that will determine its future — and could test the future health of American democracy.

“Trump is an unpopular, diminished political figure, but he has left behind an even more radical, anti-democratic party that, if it tries, will find it difficult to change in any fundamental way,” said Thomas Mann, a political scientist, author and resident scholar at Berkeley. “The energy is with the fundamentalist, populist, nativist forces within the party.”

Charles Henry

“If one were going to make a case for restoring traditional Republican values, you couldn’t find a better forum for it than an impeachment trial for Donald Trump,” added Berkeley political scientist Charles Henry. But if Republicans in the Senate don’t hold Trump accountable, Henry added, they will signal that the party has been transformed, “to some extent, into a cult of personality.”

Most elected Republicans in the House and Senate remain solidly loyal to Trump, despite the devastating case mounted by Democratic impeachment managers this week. But in the weeks since the Jan. 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol, cracks in the GOP edifice have opened wide.

High-profile figures such as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Liz Cheney, the No. 3 Republican in the House, have denounced Trump and Marjorie Taylor Greene, newly elected to Congress despite her support for conspiracy theories and violence against Democratic leaders.

Prominent Republicans, donors and GOP voters alike are leaving the party. One conservative columnist recently declared that Trump and “a significant portion of his supporters have embraced American fascism.”

But this is also true: Trump came extremely close to winning the election. Now, a war for the soul of the party, pitting old-school conservatives against Trump loyalists, could take years to resolve. Which raises the question:

What does that portend for the party’s future — and the nation’s?

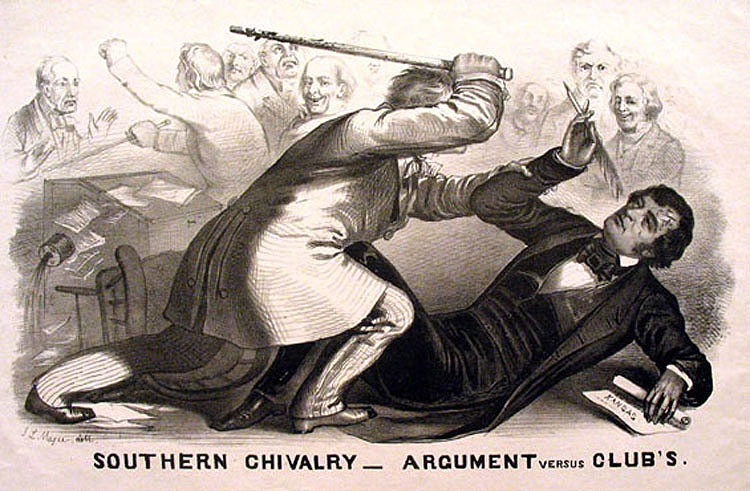

A historic lithograph depicting the severe beating of U.S. Sen. Charles Sumner by U.S. Rep. Preston Brooks of South Carolina. The 1856 attack on the floor of the Senate left Sumner near death, and was seen as an ominous signal of nation’s irreconcilable differences over slavery. (Wikimedia Commons via John L. Magee)

We’re still fighting the American Civil War

In the early morning hours after the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, as exhausted lawmakers resumed the process of certifying the victory of Democrat Joe Biden, U.S. Rep. Conor Lamb (D-Pa.) rose and condemned the lies advanced by Trump and many Republican lawmakers: that Democrats employed massive fraud to steal the election. His impassioned address nearly started a brawl on the House floor.

For Berkeley historian David Henkin, the moment inspired a flashback to 1856, four years before the start of the Civil War.

David Henkin (UC Berkeley photo)

U.S. Sen. Charles Sumner delivered a blistering condemnation of slavery, specifically calling out his colleague, Sen. Andrew Butler of South Carolina. Butler’s cousin, U.S. Rep. Preston Brooks, came to the Senate three days later and battered Sumner with a cane. Butler’s allies blocked those who tried to stop the beating, and though Sumner was nearly killed, the attack was cheered across the South.

That assault “is often seen today as some kind of rehearsal for the Civil War,” said Henkin, whose research is focused on 19th century America. “It was one of the events that made clear that slavery was not a political conflict likely to be resolved through compromise.”

Henkin draws a direct line from that day in 1856 to the 2021 insurrection — from slavery to the failure of Reconstruction, from the court-enforced segregation of the Jim Crow era to the “Southern Strategy” that propelled Richard Nixon to power in the 1960s and ‘70s, and to the 2016 election of Trump.

When white supremacists and other radical Trump supporters invaded the Capitol on Jan. 6 and carried the Confederate Stars and Bars before Sumner’s portrait in the Rotunda, that, to Henkin, expressed their commitment to the United States as a nation for white people.

During the Civil War, “the South was fighting for white supremacy, not just for slavery,” he said. “And so, for people who believe that the United States is fundamentally a nation for white people, the Confederate flag is an apt symbol of their cause and an apt expression of their patriotism.

“It does seem like they’re still fighting the Civil War.”

A Black president — and a primeval white backlash

When President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965, that precipitated a realignment of America’s two dominant parties, Henkin said. Segregationist Democrats in the South shifted to the Republican Party, and the party’s identity as an opponent of racial equality was cemented.

Henry underscores the point: In every election since 1968, the Republican Party has won the majority of white votes.

The popularity of Barack Obama — and his election as the first Black president in U.S. history — created tensions in a Republican Party torn on issues of race, scholars say. (Wikicommons photo by Sage Ross)

At the same time, though, the nation has become more diverse. With the election of Democrat Barack Obama in 2008, tensions over race multiplied within the GOP.

The Tea Party political movement, founded soon after Obama took office, preached old-school fiscal conservatism, but research co-authored at UC Berkeley concluded that racism was a powerful motivator for adherents. Many in the party were preoccupied with the “birther” conspiracy theory that Obama was not born in the United States and so was not a legitimate president.

When Obama won re-election in 2012, defeating Republican Mitt Romney, a faction of party leaders prepared a detailed “autopsy” with a core conclusion: To win in a changing America, the GOP had to widen its appeal to women, people of color and LGBT communities.

Republican voters, however, chose another path.

A sense of threat, amplified and distorted

Timothy R. Tangherlini (UC Berkeley photo)

Timothy Tangherlini is a folklorist in the Department of Scandinavian Studies at Berkeley, and his work has explored how people use stories to organize communities and how “cultural ideology” is transmitted. Today, he is working with colleagues to use advanced computational technology to discern conspiracy theories that are emerging through social media.

Fox News and other media with a strong right-wing slant have transformed the political landscape in the 21st century, and Tangherlini said the emergence of smart phones and social media in the past 15 years have allowed conservative ideology to travel farther and penetrate deeper, with less regulation.

A key to the success of right-wing communicators is understanding an elemental trait in human culture: People are bound together by a shared sense of threat, Tangherlini said. They come together to identify threats and develop solutions. But new technologies can intensify and distort those threat assessments — and this, he said, is how they have supported the radicalization of voters on a mass scale.

During the insecurity that came with the Great Recession and demographic change, people could find welcoming new communities on Facebook or Twitter, and with just a few keystrokes, they could find other people who had a shared their sense of threat, other people who understood.

In a neighborhood or in a workplace, wild ideas and conspiracy theories would likely be challenged and discredited. But online, such reality-based voices typically abandon the chatroom, leaving the discussion to like-minded people.

Armed protesters at the Michigan state capitol last year rejected Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s orders to keep people at home and businesses closed to check the spread of the COVID-19 outbreak. (AP photo by Paul Sancya)

Who’s taking our guns? Who’s stealing the election?

Trump exploited that, whether by instinct or intent. Fanning outrage at the supposed carnage of American cities, or at imagined caravans of immigrant criminals, he spoke to the id of his voters, to their primal anxieties. He identified the sources of threat — and positioned himself as the defender-in-chief.

Tangherlini imagines the narrative in a pro-Trump chatroom: “’Who stole the election? Well, it was those Democratic lawmakers. Why did they do it? Well, they’re backed by these, you know, billionaires. Why are the billionaires backing the Democrats to steal the election? Because the Democrats are going to come in and take our guns. … They’re going to give political power to minorities. What are we going to do about this?’”

People often see threats as coming from an external source — from outsiders, from aliens, Tangherlini said. “They could say the source is literally not human: ‘They’re coming from outer space.’ We saw that in Marjorie Taylor Greene’s discussion of space lasers run by Jews.

“So, this is where you get into the incredible power of narrative to both dehumanize and propose strategies for dealing with a perfectly fictional threat. Now, you have dehumanized them — and it’s easier for humans to kill things that are not human.”

That, Tangherlini suggested, is the sort of algorithm that has helped to drive radicalization and the potential for violence in Trump’s base.

Is the Republican Party an anti-democratic movement?

In a Facebook advertisement, GOP congressional candidate Marjorie Taylor Greene posed with a rifle next to photos of next to Democratic U.S. Reps. Rashida Tlaib, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ilhan Omar. Facebook ultimately banned the ad, but Greene went on to win her election in Georgia.

Mann, affiliated with the UC Berkeley Institute for Governmental Studies (IGS), has charted the GOP’s increasingly radical nature for nearly two decades in books such as It’s Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided with the New Politics of Extremism (2016, Basic Books).

Over the past generation, Republicans “succeeded electorally by generating distrust of government, mobilizing those aggrieved by finding themselves behind, and suppressing the votes of racial minorities,” Mann said in an interview. “The movement towards a ethno-nationalist populism is at the root of the party’s radicalization.”

Today, even as some GOP leaders challenge the drift toward authoritarianism, and as thousands of Republicans quit the party, the ranks of the radicalized may be growing.

Recent research has found that over 70% of Trump voters believe, incorrectly, that he won more votes than Biden. A new poll reports that almost 40% of Republicans believe violence may be necessary to preserve “the traditional American way of life.”

Another recent poll suggested that almost a third of Republicans have a favorable view of QAnon, which has been described as a mass delusion and a violent security threat.

Voters nevertheless sent two past QAnon supporters — Greene and Lauren Boebert of Colorado — to Congress in the last election. When Democrats stripped Greene of her committee assignments, her popularity rose among GOP voters.

Are GOP leaders are causing this radicalization, or simply following Trump’s lead out of fear for their jobs? That’s not always clear. But few in the party have done much to discourage it.

True believers: a ‘frightening’ break from reason

Hours after the insurrection left five people dead, 139 Republicans in the U.S. House — more than two-thirds of the GOP delegation — joined votes to overturn certified election results that had gone against Trump. In effect, they embraced a conspiracy theory that would undermine democracy itself.

Susan Hyde (UC Berkeley photo)

“A number of Republican-elected officials seem to be under the impression that they can lie to their supporters with impunity, which is itself dangerous for democracy,” said Berkeley political scientist Susan D. Hyde, whose research has focused on democratic backsliding. “This is not the stretching of the truth that politicians are known for, but something that is far more damaging.”

Often, scholars and security experts say, that anti-democratic behavior finds its form in racism.

In remarks this month to a Berkeley audience, former U.S. Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson warned of “a strand in our society that is racist, intolerant and prone to violence.”

“This segment of our population has been told it’s OK to crawl out from your rock,” Johnson said. “They have been emboldened by national leadership who say, ‘You’re special people,’ and, ‘There is good on both sides,’ and therefore it’s OK to go to Charlottesville and demonstrate your hate in the open or go to the U.S. Capitol and engage in … an insurrection.”

Henry worries that the divisions in American society are now so profound that we can no longer reason together to solve problems. In a democracy, he said, “you count on rational arguments,” but when “true believers” continue to insist on election fraud and other conspiracy theories — without any basis in fact — that “leads you to question whether they’re susceptible to rational argument.”

“Once you lose that sort of trust,” Henry said, “then democracy becomes problematic because you don’t trust your neighbor to do the right thing. And that’s frightening.”

Impeachment (probably) will not cure the GOP

In the aftermath of the insurrection, remarkable expressions of resistance and anger rose from an unexpected source: top leaders of the Republican Party, who in the past had supported Trump.

President Donald Trump addresses militant protesters before they marched to the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. (Video image via Channel 9 News Australia)

When Trump demanded that Vice President Mike Pence intervene in the vote-certification process and deny the victory to Biden, Pence refused. That enraged Trump, and the insurgents who invaded the Capitol chanted “Hang Mike Pence!”

Trump had “summoned this mob, assembled the mob, and lit the flame of this attack,” said Cheney. McConnell, the Senate’s Republican leader, privately welcomed the Democrats’ impeachment of the president and publicly called Greene “a cancer for the Republican Party.”

Steven Hayward speaks at a UC Berkeley event in 2017. (UC Berkeley photo)

McConnell is “a very practical politician,” focused on keeping a Republican majority in the Senate, said conservative author Steven Hayward, a Berkeley Law lecturer and visiting scholar at Berkeley’s IGS. “His dilemma reduces to this: He thinks Trump is a liability, and he blames Trump for costing Republicans two Senate seats in Georgia. … He’s found it difficult and frustrating to work with Trump from the beginning.”

Still, even after a powerful case presented by Democratic impeachment managers, Senate Republicans almost certainly will not convict Trump. McConnell himself has voted that the impeachment is not constitutional because Trump is out of office.

“The Republican Party has, I think, begun to confront the Trump-led authoritarian wing of the Republican Party,” Hyde told The New York Times. “The importance of this confrontation for the future of U.S. democracy cannot be overstated. If the Republican Party remains anti-democracy, then the path to restoring functional if imperfect U.S. democracy becomes nearly impassable.”

Imagining a return to normalcy, or something like it

This is the crossroads at which the Republican Party finds itself. Few, however, see an obvious course to deradicalization.

Trust has so fractured among competing U.S. cultures and communities that millions of Americans do not believe the verifiable fact of Joe Biden’s election victory in 2020. Addressing that breakdown in trust will be an enormous challenge, Berkeley scholars say. (AP photo by Alex Milan Tracy/Sipa USA)

For the past four years, Tangherlini said, Trump and others in the GOP led 40% of the electorate to embrace a narrative of political resentment and revenge that culminated in a violent attack on the seat of American democracy. Now, he asked, “what is the story that the Republican Party wants to tell that will bring back 74 million people?”

That process, he predicted, could take far more than four years.

Henry worries that Republicans will continue to use racially divisive strategies to galvanize white voters and win elections. In the insecurity of the pandemic and struggling economy, he said, “people are susceptible to autocratic and dictatorial appeals.”

Others, however, suggested that the tide may already be running against the radicals. Trump is out of office, and he is beset by legal and business troubles. Banned from Twitter, he has lost his most powerful tool for inciting his legions.

Jennifer Chatman (UC Berkeley photo)

Jennifer A. Chatman, a researcher on leadership and organizational cultures and associate dean at Berkeley Haas, said Trump has damaged the GOP, just as other narcissistic leaders have damaged their companies.

“Everybody’s been traumatized by Trump, including the Republicans,” explained Chatman, a social psychologist. “They lived for four years under his reign and under the fear that he would come after them if they didn’t show allegiance.”

Trump hasn’t been gone a month, she said, and fear still has a hold. But criticism from McConnell, Cheney and other GOP leaders may give cover to colleagues who want to stand down from extremism. Psychologists, she said, call it “social proof”: Before we decide how to behave at the office or at school, we look around at how other people are behaving.

In Chatman’s forecast, a similar process may play out among some Trump voters. As Biden takes over, and the four-year blitz of Trump communication fades, they may begin to see the world in a new way.

“They may look around and say, ‘I’m actually not better off than I was before Trump took office,’” she said, “’And, you know, Joe Biden is actually trying to do some good things. So, why are we talking about Jewish lasers in space? What does that have to do with whether I can keep my business open?’”

In every era, Hayward suggested, political success and failure come down to such questions.

Trump in 2020 increased his share of votes among communities of color, but lost support among white suburban voters. His “recklessness,” Hayward said, divided the party and may have cost the GOP the presidential election and control of the Senate.

Will the party split? Certainly not, he said. It’s more likely that party leaders will back primary election challengers who can defeat divisive figures like Greene. In such ways, the party will evolve, making adjustments so that it can maintain its base, extend its gains and reverse its losses. How to solve that equation? The answer can’t be known today — it will depend on Biden’s performance and on other unforeseeable factors.

Because of the party’s post-Trump divisions, “the midterm elections in 2022 may be tricky,” Hayward said. “But I think by 2024, an awful lot of the stuff happening right now is going to be far in the rearview mirror.”

That’s the natural course of politics, he said, “unless Trump is the candidate again, which is still a question.”