How legacies of racism hinder vaccination among communities of color

Vaccine hesitancy is just one of a constellation of factors that prevent Black, Latinx and Native American people from accessing the protective shot

March 15, 2021

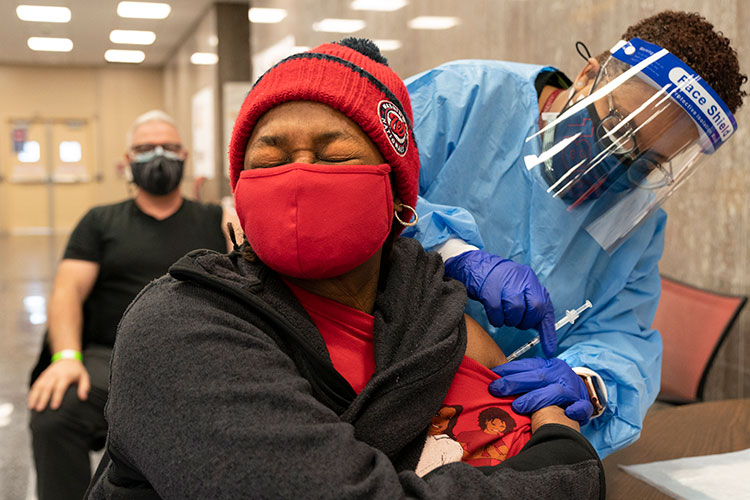

Jorie Winbish, 56, of Washington, D.C., reacts as she receives her second dose of the COVID-19 vaccine at a clinic at Howard University in Washington, D.C., Across the country, vaccination rates among communities of color are falling behind those of white people, and vaccine hesitancy is just one of a constellation of factors contributing to these disparities. (AP Photo by Jacquelyn Martin)

Krista Cortes described the mood in Pauley Ballroom as solemn yet hopeful on the February morning she received her first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine.

Cortes, a doctoral student in education at UC Berkeley, qualified for the vaccine because of her role as a community advisor at University Village, where she assists residents with lock-outs and other emergencies. But, as an Afro-Latina woman, she said that the history of medical racism in the U.S., combined with her own negative experiences with medical providers, initially led her to be skeptical of the new treatment.

“As a Black woman and as a Latina woman, I’ve experienced firsthand, and also have seen and heard stories about people who had not been treated well, or who had experienced sub-par treatment at the hands of doctors,” Cortes said. “And, as a student, I’m currently learning the many ways in which Black and Latinx bodies have been exploited by the medical community.”

On her mind were examples of medical exploitation including the notorious Tuskegee experiment, in which health officials monitored the progression of Syphilis in Black men without informing them of their diagnosis or offering them treatment, as well as the forced sterilization of Latinx people in Puerto Rico and other parts of the U.S.

Cortes wasn’t alone in considering America’s racist, tortured history of medical care when she got her COVID-19 vaccine.

Berkeley News will examine racial justice in America in a series of stories.

Across the U.S., communities of color have been hit particularly hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, for reasons public health experts have long recognized. Black, Latinx, Native American and Asian people are more likely to live in areas with bad air pollution and little access to quality doctors or good insurance. They are also more likely to work in front-line service jobs that offer little protection from the virus and to live in dense housing that makes social distancing difficult.

And data now indicate that those same communities face another barrier: They’re among the least likely to access early doses of any of the COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccination rates among Black, Latinx and Native American communities are lagging in Los Angeles County, one of the hardest-hit regions in California, and this pattern holds throughout the rest of the state.

Mistrust in the vaccine, born from both historic and current experiences of medical mistreatment, may be one factor leading to these lower vaccination rates. However, a constellation of other factors – many stemming from the same structural inequalities that put these communities at higher risk of COVID-19 – are also creating barriers that prevent them from accessing the vaccine.

“I really see Tuskegee as an exemplar of decades of mistreatment that may lead to vaccine hesitancy, but that is not really the reason that we are not seeing as much uptake of the vaccine in Black communities in particular and in communities of color in general,” said Tina Sacks, an assistant professor of social welfare at UC Berkeley. “Mistrust is a huge factor because of Tuskegee, but I think what Tuskegee really teaches us is that access to care remains a major issue. The barriers to care are numerous and very entrenched, and they are directly related to historical patterns and also contemporary instances of structural discrimination”

The Tuskegee experiment, which ran from 1932 until 1972, is just one in a long list of medical experiments carried out on marginalized communities without informed consent, some of which continued into the 1990s. These include an experimental measles vaccine given to Black and Latinx children in Los Angeles, psychiatric tests in which Black and Latinx boys were given intravenous doses of the diet drug Fen-Phen and genetic testing using blood samples from the Native American Havasupai Tribe.

In addition to instances of blatant medical exploitation, many people of color also report everyday experiences of being treated poorly by doctors, including dismissal of pain and other symptoms and delay or denial of treatment. These experiences, tied with the challenges of accessing regular affordable health care, can both erode trust and block access to accurate medical information.

Krista Cortes, a graduate student in education at the University of California, Berkeley, receives her first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine in UC Berkeley’s Pauley Ballroom. Though the history of medical exploitation and mistreatment of Black and Latinx communities in the U.S. initially gave her a “healthy skepticism” of the vaccine, she ultimately decided it was important to do her part to help stop the spread of COVID-19. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

“There’s a lengthy history of vulnerable populations in this country being subjected to unethical medical testing, and these ethical breaches can increase their sense of mistrust,” said Denise Herd, a professor of behavioral sciences at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health. “Bad experiences with doctors can also discourage people from looking to the medical community as a source of information and a source of care.”

A January 2021 poll from UC Berkeley’s Institute for Governmental Studies suggested that, while willingness to take the vaccine among communities of color has risen significantly since October, Black, Latinx and Native American Californians remain less willing to take the vaccine than white Californians.

In the survey, 66% of Black respondents, 66% of Native American respondents and 71% of Latinx respondents indicated that they would be “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to get the vaccine once it became available, compared to 79% of white people.

“These groups, despite the histories of medical racism, also know that they are the most likely to suffer, and they’ve probably also seen a lot of suffering in their families,” said IGS co-Director Cristina Mora. “The increase in interest might be an indicator of some of the work of community-based health organizations that specialize in vulnerable populations and can really tailor messaging to them.”

Sacks pointed out that willingness to get the vaccine among Californians of color is actually on par or higher than that of Republicans, who are predominantly white, and stressed that disparities in vaccination rates should be attributed to difficulties accessing the vaccine, rather than to unwillingness to take the vaccine.

Many people from lower income communities of color lack health insurance that would give them access to the vaccine. Others may not have access to a stable internet connection to sign up for a vaccine appointment, or to transportation to get to and from a vaccine appointment. And, because of disinvestment, hospitals and clinics often struggle to stay open in low income neighborhoods, meaning people from these communities have to travel farther to access care.

According to Herd, even the decisions about who to prioritize for vaccination have had the effect of excluding some communities of color.

“California and many other places started off vaccinating people 75 years and older, but the life expectancy rates among many people of color and in certain areas are much lower than that.” Herd said. “In some groups, such as the Latinx population, the highest rates of COVID-19 are among the younger ages, so by setting the age priority, it also automatically reduces the number of people who are at most risk in that population from getting vaccinated.”

Members of the UC Berkeley community wait for COVID-19 vaccine appointments outside of Martin Luther King Jr. Student Union. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

Prioritizing marginalized communities for vaccination, and engaging the help of local community health organizations in providing vaccines, could help both increase trust and ensure that distribution is equitable, Herd and Sacks said.

“My recommendation is that we really need a place-based approach, because, as a result of segregation, we have segregated health problems,” Herd said. “Health disparities, health inequities and health problems are concentrated in certain zip codes. We know that in Berkeley, there are two zip codes where the rates of all kinds of chronic and infectious diseases are the highest. So why wouldn’t we target those areas for receiving the vaccine?”

Herd thinks that California’s new plan to reserve 40% of its vaccine supply for low income residents is a step in the right direction. Community-based clinics and organizations, such as Unidos en Salud in San Francisco, also have a major role to play in both building trust in the vaccine, and ensuring that those who need it are able to access it, Herd said.

Word-of-mouth and peer support among communities can also help more people feel comfortable getting the vaccine, Sacks said.

“I think that we’re going to have to take this vaccine to people as opposed to expecting people to come to get the vaccine, whether that’s using mobile clinics or pop-up clinics in neighborhoods,” Sacks said. “Word-of-mouth also helps. People often will trust someone in their community or family who’s gotten the vaccine and could say, ‘Listen, let’s go do this together.’”

Despite her initial skepticism about the COVID-19 vaccine, Cortes ultimately decided that getting vaccinated was an important way she could help limit the spread of the disease. She also wanted to demonstrate the importance of vaccination to her two children, who accompanied her to her vaccination appointment.

“One of my kids was eight months, so he won’t remember it, but we thought it was important to have the photos to look back at, and show that this is one way that we can do our part,” Cortes said.

By getting vaccinated, she may have paved the way for other family members to get it, too.

“Some of my relatives were skeptical about the vaccine, but, after hearing that I got it, they decided that it was okay,” Cortes said.