World-renowned anthropologist Paul Rabinow dies at 76

A celebrated Francophile and theorist known for his interpretations of Foucault

April 23, 2021

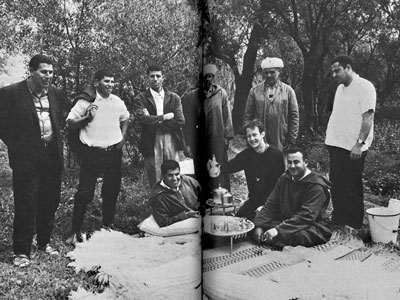

Paul Rabinow, an acclaimed UC Berkeley anthropologist, died on April 6, 2021. (Photo by Saad A. Tazi via Wikimedia Commons)

Paul Rabinow, a world-renowned anthropologist, theorist and interlocutor of French philosopher Michel Foucault, his former comrade, died from cancer at his home in Berkeley on April 6. He was 76.

A professor emeritus of anthropology, Rabinow joined the UC Berkeley faculty in 1978 after earning his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. He retired in 2019.

During his more than four decades at Berkeley, Rabinow’s scholarship and pedagogy traversed such diverse lines of inquiry as the anthropology of reason, medical anthropology and the ramifications of synthetic biology.

“Paul was a profoundly energetic survivor of 20 years of cancer, during which time he produced many of his most important works,” said UC Berkeley anthropology professor emerita Nancy Scheper-Hughes, Rabinow’s longtime friend and colleague.

Rabinow, seated second from the right, at a tea ceremony in Morocco. (Photo by Paul Hyman)

His seminal Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco, published in 1977, was considered a model for conducting ethnographies and fieldwork.

In the 1990s, Rabinow coined the concept of biosociality as the shared experience of sickness and suffering, particularly with respect to the AIDS epidemic.

“Paul was as much a historian of the contemporary, a philosopher, or a molecular scientist as he was an anthropologist,” Scheper-Hughes wrote in an online tribute to Rabinow.

“His classic texts are read around the scholarly world, and his invitation to Foucault to give a series of lectures brought the house down and led to UC Berkeley briefly renamed ‘Foucault U,’” she wrote. “Paul, I missed saying goodbye to you by a day and now it will be a multitude of days of regret and sorrow.”

Rabinow’s critically acclaimed writings include Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics (1983), which he co-wrote with UC Berkeley philosopher Hubert Dreyfus; The Foucault Reader (1984); Making PCR: A Story of Biotechnology (1993); Essays on the Anthropology of Reason (1996); French DNA: Trouble in Purgatory (1999); Anthropos Today: Reflections on Modern Equipment (2003); and Marking Time: On the Anthropology of the Contemporary (2007).

A sharp wit and tongue

Known for his sharp intellect and urbane style, Rabinow could be alternately amiable, impish and petulant.

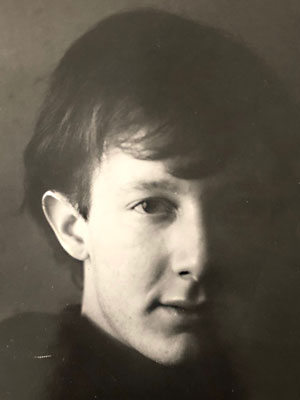

A portrait of Paul Rabinow as an undergrad at the University of Chicago in 1963. (Photo by Paul Hyman)

“Paul Rabinow was neither easy nor particularly nice, but the intellectual rigor he demanded from me, and the kindness he showed me, will be with me forever,” tweeted Minda Murphy, a researcher with a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from UC Berkeley.

Murphy’s was among dozens of online homages to Rabinow written by peers and former students around the world.

Gabriel Coren, a researcher at the Berggruen Institute in Los Angeles and one of Rabinow’s former doctoral students, recalled Rabinow’s brusque response to an incoming graduate student’s question about the department’s perks and resources, compared to those of rival institutions.

“’As with any university today, it has problems. Many problems,’” Coren recalls Rabinow telling the graduate student at a welcome reception in 2012. “’But this is Berkeley, a public institution, and that means something worth thinking about. Look, if you just want to make sure that the bathrooms have brand new toilets and fancy trashcans, you should probably just go to Chicago.’”

“That was Paul: frank, humorous, prone to cantankerousness, and a defender of the dignity of one’s place,” Coren recounts in his online tribute to his former advisor.

‘Not fully American’

Paul Rabinow was born on a U.S. Army base in Florida on June 21, 1944, to Irving and Mildred Rabinow. His parents were social workers and the descendants of Russian Jewish immigrants. When he and his younger sister, Naomi, were young, the family moved to Queens, New York, and Irving Rabinow worked for the Jewish Child Care Association in Brooklyn.

In elementary school in the Sunnyside neighborhood, Rabinow befriended Paul Hyman, another boy whose parents had made the move from a Florida military base to New York. Right from the get-go, “Rab was a fighter,” recalls Hyman, now a New York-based photographer.

In a 2008 interview, Rabinow described a childhood in 1940s and 50s New York where anti-Semitism and McCarthyism loomed large: “As a child, I was passionately involved in sports, roller hockey in particular; a strange obsession as it was mainly played by Irish Catholics and the Jews played basketball,” he said. “I was the only Jew in a Catholic Youth Organization league.”

“I was brought up to believe that America was simultaneously probably the best place in the world to be for a Jew but also not very trustworthy and not very safe,” he continued. “I was of America but not fully American. My parents’ experience in the South and Midwest, when my father was in the army, of blatant racism and anti-Semitism, was foundational.”

The French Connection

After graduating from Stuyvesant High School, he gained admission to the University of Chicago and earned a bachelor’s degree in 1965 and a master’s degree two years later. At the University of Chicago, he met French ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss and learned about European perspectives. In graduate school, he spent a year at École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris, and honed his French.

In 1969, he traveled to Morocco, where he conducted ethnographic studies that resulted in his Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco. While there, he invited Hyman to visit him, and bring his camera and lots of film. Hyman came and took hundreds of photographs, dozens of which were published in scholarly books, and several of which have since been exhibited in museums and galleries.

Rabinow, left, with Paul Hyman in Tangier in 1969. (Photo courtesy of Paul Hyman)

Rabinow completed his doctoral studies at the University of Chicago under the tutelage of philosopher Richard McKeon and anthropologist Clifford Geertz and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology in 1970.

After, he took a job at an experimental school in New York City. Then, by some fluke, he ran into UC Berkeley sociologist Robert Bellah, who let him participate in a National Endowment for the Humanities seminar at Berkeley.

“That was a major turning point,” he recounted in a 2008 interview. “Bellah helped me get ‘Reflections’ published. I met Hubert Dreyfus, and a whole range of other connections opened up. I discovered California, which seemed an exotic land; that led into my learning from Dreyfus about Heidegger and Wittgenstein; that set the scene for the entry of Foucault into the picture. I got a job at Berkeley.”

‘Sophistication and energy’

And he certainly made an entrance in the anthropology department in 1978.

“Rabinow brought a new sophistication and energy to anthropological inquiry that participates in broad conversations about contemporary modes of living and life forms,” wrote Aihwa Ong, a UC Berkeley anthropology professor emerita, in her tribute to her longtime friend and colleague.

In 1980, Rabinow was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim fellowship. It was around that time that he met Foucault, who had been been visiting Berkeley off and on since the mid-1970s. Their collaboration resulted in the 1983 publication of Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, followed in 1984 by The Foucault Reader.

That same year, Foucault died in Paris from HIV/AIDS-related complications. Rabinow grieved the loss of his comrade, and went on with his life. He married Marilyn Seid, a Chinese-American San Francisco native who ran a language proficiency program for Berkeley graduate student instructors. They had a son, Marc, whom they raised in Berkeley to be bilingual in English and French.

Meanwhile, activism in the Bay Area was reaching a fever pitch in the face of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Grassroots activist groups like the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (Act Up) fought to destigmatize the disease and to build political support.

Scheper-Hughes convinced Rabinow to co-teach with her UC Berkeley’s first course about the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In one class, she said, two guest speakers from very different socio-economic neighborhoods in San Francisco compared their T-cell counts and explained how the virus had disrupted their lives.

Rabinow with anthropology professor Nancy Scheper-Hughes in a classroom on campus.

“That’s when Paul came up with the idea of biosociality,” Scheper-Hughes wrote. The revelation led to his paper, “Artificiality and Enlightenment: from Sociobiology to Biosociality.”

At one particularly heated panel discussion in 1992, some audience members objected to Rabinow bringing up Foucault, calling the late French philosopher a closet case who did not go public with his AIDS diagnosis, Scheper-Hughes wrote.

“Paul ended the panel defending his right to speak on behalf of the man that he loved. He feared that Foucault had contracted HIV/AIDS in the bathhouses of San Francisco during his invited series of lectures at UC Berkeley,” Scheper-Hughes wrote.

The ethics of biotech

Next, Rabinow turned his focus to the science and ethics of California’s burgeoning biotech industry. In addition to his research, teaching and mentoring at Berkeley, he served as director of the Anthropology of the Contemporary Research Collaboratory, which he founded with anthropologists Stephen Collier and Andrew Lakoff. He was also director of human practices for UC Berkeley’s Synthetic Biology Engineering Research Center (SynBERC).

Among other honors, he held fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities and a professional training fellowship in molecular biology from the National Science Foundation. He also served stints as a visiting Fulbright professor at the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro and at the University of Iceland.

Tobias Rees is the Reed Hoffman Professor at the New School of Social Research.

Now and then, he returned to Paris where he taught at École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and, later, at École Normale Supérieure. So strong were his ties to the City of Light that the French government named him Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, and École Normale Supérieure awarded him the visiting Chaire Internationale de Recherche Blaise Pascal.

In its obituary for Rabinow, the French newspaper Le Monde dubbed him “the most Francophile of North American anthropologists.”

He is survived by his wife, Marilyn Seid-Rabinow, of Berkeley; son, Marc Rabinow, of New York; and sister, Naomi Landau, of New Mexico.

A campus memorial to celebrate his life and legacy is planned for this fall.