Blockeley’s back, with an 1893 campus and a Bancroft Library archive

Now a student organization, Blockeley also will hold its second annual pandemic-era commencement on Saturday, May 15.

May 7, 2021

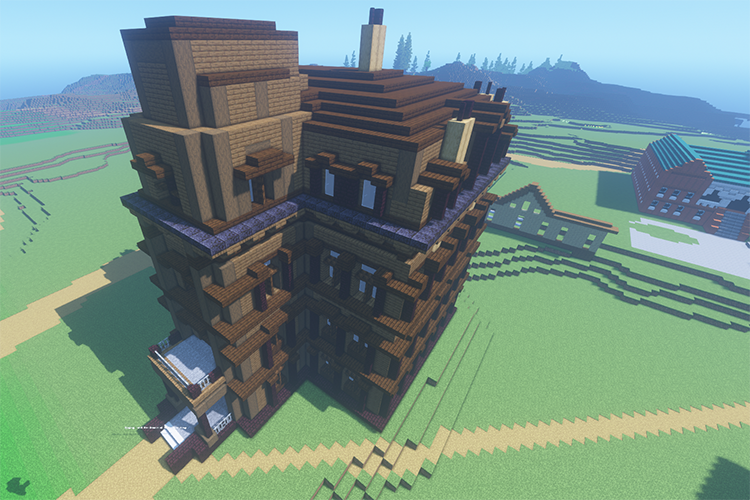

Blockeley lives on, with its builders constantly creating new images of the campus in the Minecraft video game. The virtual campus can be walked and flown through in-game on May 15, at the student club’s second annual Blockeley commencement. (Blockeley image)

Last year’s mock commencement at Blockeley University, a fantastical virtual model of UC Berkeley created in the Minecraft video game, made headlines as an imaginative response to the COVID-era postponement of Berkeley’s 2020 graduation ceremony.

This spring, Berkeley will hold its own Class of 2021 Virtual Commencement, at 9 a.m. on Saturday, May 15. But Blockeley is back, too, and bigger than ever.

Now organized as a campus student organization called Blockeley, the students and alumni who last year painstakingly replicated more than 100 of Berkeley’s buildings and landmarks with a game many of them first played as tweens will hold a second annual Blockeley commencement in Minecraft at 10 a.m. on May 15.

The group of about 30 active members began planning in late 2020 to hold a repeat ceremony in 2021, unsure if the campus would have its own. Chancellor Carol Christ and Vice Chancellor Marc Fisher — or, rather, their avatars — again will take part, in-game, and give remarks.

Then, a new Minecraft server will welcome participants to explore Blockeley’s latest creation in the video game — Blockeley 1893, a replica of the university in the 1890s, during the Victorian era, when only about 15 brick and wood buildings and some 2,000 students dotted a much more apparent natural landscape, with uninterrupted views of the hills, Strawberry Canyon and the bay.

Only South Hall survived that time period: By the early 1900s, following an international design competition, the growing university would get a more distinguished look — “to have a unique effect in the world,” the UC Regents said. The new, grand, typically granite-clad buildings included Doe Library, California Hall, the Campanile and Hearst Memorial Mining Building.

“Berkeley is a space that’s changed so much over history, and I thought we should make a version of campus that no living human being has ever seen,” said alumnus Nick Pickett, a member of Blockeley’s alumni board. “I’m obsessed with time travel, and I have always wanted to literally walk through the past. Minecraft being used to recreate historical sites is about the closest we can get to spaces that no longer exist.”

So, Pickett and sophomore Christian Nisperos, Blockeley’s president, turned for background to former campus planner Harvey Helfand, who quickly provided historic photos and advice, and to Steve Finacom, a former campus planning analyst and community historian. Pickett and Nisperos also viewed documents, photographs and drawings of Berkeley from that era at the Bancroft Library and in the Berkeley Library Digital Collections.

Christian Nisperos (left) is the president of Blockeley, a student club. Berkeley alumnus Nick Pickett is a member of Blockeley’s alumni board. (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

“We found images at the Bancroft Library of buildings that hadn’t come up in an online search,” said Nisperos, a mechanical engineering major. “It was quite surreal; I went to the library and handled hundreds of actual historical documents from that time period.”

Not only did Blockeley, the club, become mesmerized by the Bancroft’s holdings, but archivists at the library are smitten with Blockeley, for which they are creating a new digital archive.

“I don’t know anything, really, that compares to (Blockeley) — the ingenuity of the students and their creativity, both their response to the pandemic and how they’re taking it beyond that,” said Kathryn Neal, associate university archivist at the Bancroft. “We’re in new territory here, as far as student projects are concerned.”

Said the Bancroft’s digital archivist, Christina Velazquez Fidler, of Blockeley’s 2020 replica of campus and its graduation ceremony, “It blew my mind. It was both impressive and inspiring.” The decision by Neal and Fidler to establish the Blockeley archive, the mother of two youngsters added, “turned me into the coolest mom in my kids’ school community.”

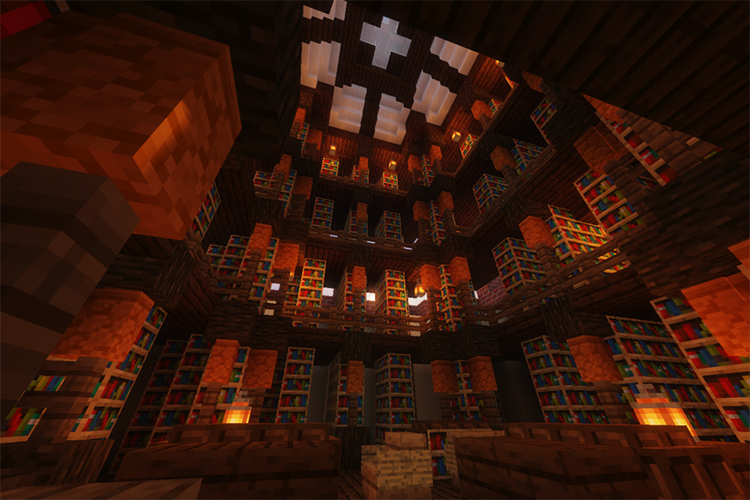

A replica of Doe Library’s North Reading Room, created in Minecraft by a Blockeley builder. (Blockeley image)

Showing the world what video games can do

After the May 2020 Blockeley spectacular, the students and alumni who’d used Minecraft to build the campus, the ceremony and the Blockeley Music Festival couldn’t fathom disbanding.

Some, like Pickett, a junior specialist at Berkeley’s Space Science Laboratory who is studying the atmosphere of Mars, found that working on Blockeley projects was a coping mechanism during many months of sheltering in place during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Blockeley was created during COVID,” he said. “It’s been a really important diversion, and I’m really fortunate to have this Blockeley family.” He added that the virtual nature of Blockeley allowed its members to easily interact socially at a safe distance.

After becoming an official Berkeley student club — alumni can’t be members, but are partners — Blockeley “definitely didn’t take a break,” said Pickett. It joined an intercollegiate, international Minecraft league, took part in an e-sports event, hosted Fourth of July and Halloween activities, developed Blockeley merchandise for the Cal Student Store, and helped a child stage a Black Lives Matter protest at Blockeley.

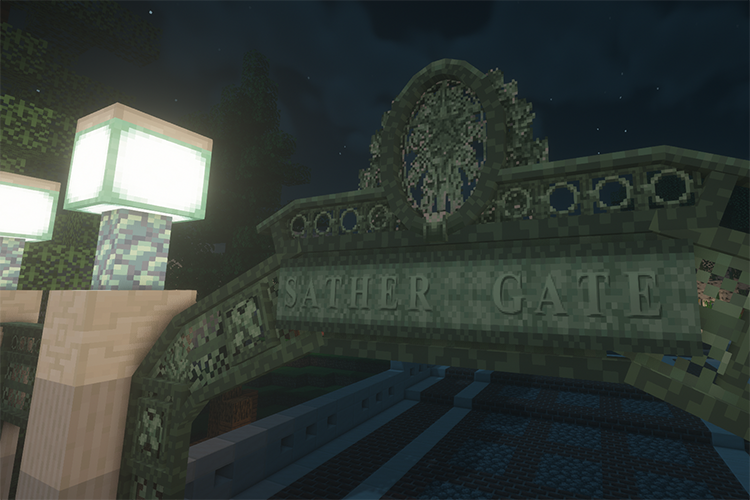

“Over the summer, we got email from a 10-year-old, Dean, and his mom, and they were asking how they could host their own BLM protest for people worried about getting COVID at public events. So, we said, ‘Do you want to host your protest on our server?’” said Pickett. “Dean designed signs for people to hold, and there were about 50 people who walked along a route through campus and put up a BLM memorial in front of Sather Gate.”

Blockeley’s version of Berkeley’s Legends Aquatic Center, which opened in fall 2016 and includes the first diving tower on campus. (Blockeley image)

The group then chose its newest project: Blockeley 1893.

“Our founder, Bjorn (Lustic), wanted to show the world that video games are so much more than modes of entertainment,” explained Pickett, “that we could show the world how serious and universally applicable video games can be.”

Blockeley 1893 showcases campus buildings in the late 1800s that include South and North halls; stunning Bacon Hall, a combo library, museum and art gallery; the Bernard Maybeck-designed Hearst Hall, an entertainment hall that philanthropist Phoebe Hearst had moved to College Avenue to become a women’s gym; and a large glass plant conservatory, for agricultural studies, that was modeled after the London Crystal Palace and built on the site of today’s East Asian Library.

“The (UC) Botanical Garden was in front of the conservatory, where Memorial Glade is. It was full of all sorts of eclectic plantings,” said Finacom. The garden was relocated to its current spot in Strawberry Canyon in the 1920s.

“The Campanile wasn’t yet built yet, but Bacon Hall, with its prominent clock-and-bell tower, was intentionally placed at the top of what’s now Campanile Way,” Finacom said. “So, just as you look up Campanile Way now and see a bell tower and clock, at the upper end in the 1890s you also saw a tower and clock, and if you looked downhill, the other way, you saw the Golden Gate, as you do today.”

Blockeley’s interior of the Bacon Hall Library and Art Building, which opened on campus in 1881 and had an art gallery and a clock-and-bell tower. (Blockeley image)

Finacom added that the 1890s Berkeley campus “was a different world. It was a place with no automobiles, and thus, no parking shortages, just a few thousand students and a few hundred faculty and staff and electric power to only a couple buildings. The most advanced data storage devices were glass bottles and wooden cases in science laboratories, and printed books bound with leather and illustrated with engravings.

“A virtual portal like Blockeley is going to be an intriguing way to start seeing that world.”

A few creative liberties were taken with the 1893 date: Some buildings in Blockeley 1893, including the plant conservatory and Hearst Hall, were built closer to the turn of the century, but their inclusion helps illustrate the campus’s look before its early 1900s redesign.

One of Blockeley’s biggest challenges to replicating the late 1800s campus was the Agriculture Building, for which nearly all the images are from the day it burned down in 1897— several photos even show the structure on fire.

A Blockeley replica of the Agriculture Building that opened in 1888 but was destroyed by fire in 1897. Its basement became the foundation for a second agricultural building, Budd Hall, named after Gov. James H. Budd after his death in July 1908. (Blockeley image)

“Enough of the building was visible to determine what the walls looked like, but the entire roof was missing from all images, save a single, heavily-obstructed photo from the Bancroft that we found late into the project,” said Pickett. Architecture students in the Blockeley club sketched what the former building likely looked like using photos from the late Clinton Day, the Agriculture Building’s architect.

Pickett added that working in Minecraft with blocks — the game’s basic units of structure — has limits, as not all of them can be tracked to real-world equivalents, like bricks, wooden planks, stone or concrete. He said a block called “nether wart block,” for example, was used to make part of Hearst Hall, while South Hall’s windows have a birch door on either side to visually suggest the stone trim that outlines the windows’ shape.

Finacom said he’s impressed with how Blockeley has represented the buildings in Minecraft, given the game format’s constraints.

“I am glad they became interested in this project and are trying hard to make it historically representative,” he said. “It’s always a positive when people are interested in learning about the now-distant early history of a place like this, and the Blockeley project adds a new visual dimension to that learning.”

The two non-digital items that will be part of the Blockeley archive at the Bancroft Library are

a 3D version of Memorial Stadium printed from the Minecraft server and a small pin that says “hope.” (UC Berkeley photo by Irene Yi)

A Blockeley archive for the ages

At the Bancroft, digital archivist Fidler said she and Neal “from early on had been really interested in how the campus community was responding to the pandemic, and Blockeley emerged as a fascinating response. My family plays Minecraft at home, and it never occurred to me that you could re-envision what commencement could be.

“I don’t think these Berkeley students understand the impact they had on the community.”

Pickett said 15,000 people watched the 2020 Blockeley commencement livestream on Twitch, nearly 1,000 people participated in-game, and $6,000 was raised by Blockeley that day to support the nonprofit Off Their Plates. This year, donations will go to the Berkeley Relief Fund.

Christina Velazquez Fidler is the Bancroft Library’s digital archivist. (Photo by Christina Velazquez Fidler)

Fidler moved quickly to screen capture the event, and her exploration of the post-commencement party, on two different devices. She has since crawled the commencement video, which is part of the Blockeley University web archive on Archive-it.org.

She also said she is debating whether, in addition to capturing the actual Blockeley worlds that the student organization creates, she also should capture herself exploring them.

“The beauty of working at the Bancroft,” she added, “is that we don’t just work with boxes of paper: We’re always at the forefront of innovating with collections.”

Fidler and Neal met over the summer with members of the core Blockeley team to learn about the types of materials they’d created and preserved, to determine “what would have long-term historical value,” said Neal. “There were planning documents, meeting notes, the website, ample publicity, and they’d also used reference photos of the campus to create the replicas.”

Nisperos added that Blockeley also had gathered testimony from its founders and builders and chronicled enough of its early history so that it “would be enough for someone to look at what we did and understand it.”

The new Bancroft archive also will include two non-digital Blockeley items: a small bronze pin that says “hope” and a tiny 3D version of Memorial Stadium printed from the Minecraft server.

The pin’s history stems from the large word “nope” painted in September 2017 on the rooftop of McCone Hall by geography students in advance of right-ring provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos’ arrival on campus for a planned “Free Speech Week” that eventually was canceled by organizers.

“Bjorn (Lustic) had been contacted by some Berkeley students who told him they thought it read ‘hope,’ and I was obsessed with it as a symbol for what Blockeley was,” said Pickett. “I incorporated it into various designs for merchandise that never came to fruition and eventually had pins made as gifts for students and staff who made Blockeley possible.“

Said Neal of what the Blockeley team has shared with the Bancroft, “We’re interested in practically all of it, in documenting the project as fully as we can.”

Neal added that the Bancroft’s broader effort to document how Berkeley has been responding to the COVID-19 crisis includes saving email directly related to information-sharing on campus about the pandemic, such as through CalMessages, and collecting Berkeley websites that have been communicating about the evolving situation.

“It’s surreal to know that part of me, Blockeley, what we worked on, will exist way longer than any of us ever will,” said Christian Nisperos, Blockeley president, of the new Blockeley Archive at the Bancroft Library. (Blockeley image)

Pickett and Nisperos said they’re excited at the thought of Blockeley leaving a lasting impact on the world — one prompted by the pandemic — by way of an archive at the Bancroft Library. The library is one of the largest and most heavily-used libraries of manuscripts, rare books and unique materials in the United States.

“It’s indescribably amazing that something I made will outlive me, a record of something good that I helped bring into the world,” said Pickett. Blockeley is not “just about the architecture” of the campus and will continue as a “bastion of student memory,” he added, with future members of the club making their own contributions.

Said Nisperos, “I thought if I’d have an impact on the world, it would be when I’m much older. It’s surreal to know that part of me, Blockeley, what we worked on, will exist way longer than any of us ever will. Our children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren will know the people who worked on the Blockeley project and might be inspired in the future.”