Playwright Philip Kan Gotanda on growing up in California post-World War II

"You grow up in America with incidences of racism that are talked about, not talked about," says the theater professor. "You accommodate them. There are secrets. You just go along with your life."

Courtesy of Philip Kan Gotanda, copyright Diane Takei 2021

May 7, 2021

Philip Kan Gotanda is a professor in UC Berkeley’s Department of Theater, Dance and Performance Studies and one of the most prolific playwrights of Asian American-themed work in the United States. In the first episode of a three-part series, Gotanda talks about growing up in Stockton, California, after World War II and the anti-Japanese racism that he couldn’t name as a child, but that he’d go on to write about as an adult.

Listen to the other episodes in the series:

Part two: How the Asian American movement began at Berkeley, sparked creativity and unity

Part three: How do we talk about the Asian experience with Asians at the center?

Philip Kan Gotanda is a professor in the Department of Theater, Dance and Performance Studies at UC Berkeley and one of the most prolific playwrights of Asian American-themed work in the U.S. (Photo courtesy of Philip Kan Gotanda, copyright Diane Takei 2021)

Read a transcript of Fiat Vox episode #75: “Playwright Philip Kan Gotanda on growing up in California post-World War II.”

This is Fiat Vox, a Berkeley News podcast. I’m Anne Brice.

[Music: “Gusty Hollow” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Today’s story is about Philip Kan Gotanda. He’s a professor in UC Berkeley’s Department of Theater, Dance and Performance Studies and he’s one of the most prolific playwrights of Asian American-themed work in the United States.

In the first of a three-part series, Gotanda shares how growing up in Stockton, California, after World War II with an undercurrent of anti-Japanese racism shaped the way he felt about himself and would influence his work later on.

[Music fades]

Philip Gotanda: I grew up in Stockton, California, in the ‘50s and ‘60s, way back when. At that time, there was a whole vibrant Japanese American community — you went to church, you socialized. My father was a doctor. So, it was one of these things where I felt always proud because they would call my father “sensei.” It was certainly, it felt like it was a really good childhood and upbringing.

When Gotanda got older, he and his family moved to a neighborhood where most people were white. And his mother said something to him one day that made him realize that things maybe weren’t quite as good as they seemed.

Philip Gotanda: I was going to go outside to play with my friends, who were all white, and my mother, before I went out, said, “OK, Philip, you can have white friends. You can have them, and they’ll play with you, and you’ll do things together. But if anything bad happens, they’ll turn on you. Now, go play with your white friends.”

So, it kind of sums up this kind of ambivalence that you are raised with — that there’s something amiss, something historically happened, that is actually infecting you.

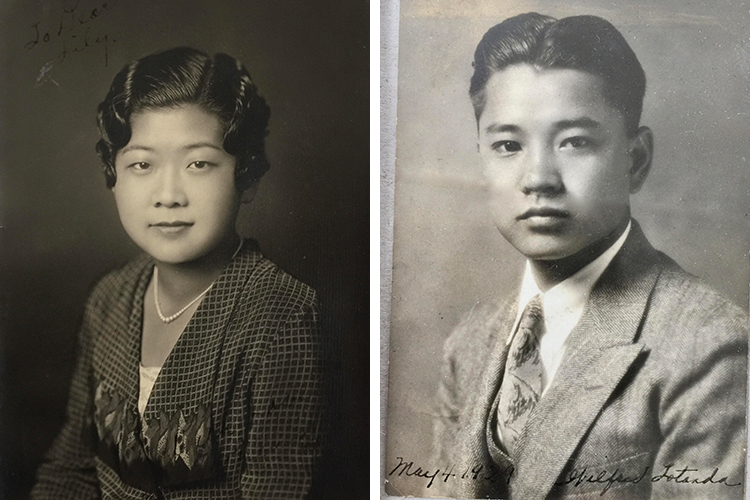

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941 during World War II, Gotanda’s parents, Catherine Matsumoto and Wilfred Gotanda, second-generation American citizens, were sent to a U.S. prison camp in Rohwer, Arkansas, where they lived until President Franklin D. Roosevelt rescinded Executive Order 9066 in 1944. (Photo courtesy of Philip Kan Gotanda, copyright Diane Takei 2021)

His parents had been among the 120,000 Japanese Americans who were incarcerated by the U.S. government in internment camps after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii in 1941 during World War II.

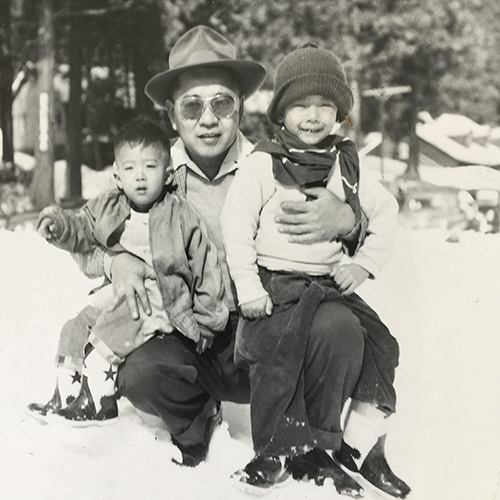

Philip (left) with his father, Dr. Wilfred Gotanda, and older brother, Neil, at Lake Tahoe, California. (Photo courtesy of Philip Kan Gotanda, copyright Diane Takei 2021)

Philip Gotanda: That community, en masse, were picked up and all sent to Rohwer, Arkansas — to Rohwer, Arkansas, of all places — and put in these camps. And they were there for about three years. They get let out, and they come back to the West Coast. Not everyone came back to the West Coast because they didn’t think it was safe. They came back to Stockton and made their lives again.

[Music: “The Terrarium” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I wasn’t aware until later about how much racism they were encountering, or anti-Japanese sentiment, hate, because of the war. And so, that was always part of growing up, but I wasn’t aware of it, I couldn’t name it, as it were.

I’ve written about the society of internalized racism — that you actually may not even know is there, but it literally is part of the land, and it comes up from the land and infects your body and it weakens you because it makes you sort of buy into, in some way, the racism.

[Music fades]

Anne Brice: I’m curious, looking back, would you have liked your parents to have shared more about their experiences in the relocation camp?

Although Gotanda and his family experienced anti-Japanese racism after the war, “I look back, and I had a good childhood,” says Gotanda. “They (his parents) were loving. I grew up fishing and playing all the American sports.” (Photo courtesy of Philip Kan Gotanda, copyright Diane Takei 2021)

Philip Gotanda: It would have been nice to know because I had all this, basically, internalized racism, self-hate, you know, which was not uncommon at that time if you weren’t white. In particular, if you were Asian. You didn’t want to be Asian, you didn’t like being Asian, you didn’t hang with Asians because it was uncool, in my generation. So, it would have helped that.

But I do know that for them to talk about those events would have been extremely painful, and it would have involved a kind of huge emotional unburdening that, at the time, there wasn’t an appropriate way for them to express that. It was all locked away, and there was no right way to do it that wouldn’t appear ugly, I think.

[Music: “The Terrarium” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Again, you know, I still look back, and I had a good childhood. They were loving. I grew up fishing and playing all the American sports. So, it’s sort of like, that’s how you grow up in America: You grow up in America with incidences of racism that are talked about, not talked about. You accommodate them. There are secrets. You just go along with your life.

[Music fades]

Philip and his mother, Catherine, in Stockton in the 1980s. (Photo courtesy of Philip Kan Gotanda, copyright Diane Takei 2021)

But in retrospect, as I left Stockton and as I became familiar and was informed more and more by the Asian American identity politics that were emergent, it sort of gave me perspective on how to look back on my growing up in Stockton. And I began to reinterpret it and reframe it. And some of my early works are about Stockton from the vantage point of the 20th, 21st century, looking back where the characters are more familiar with what’s happening beneath the surface.

[Music: “The Terrarium” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Gotanda would go on to write about 40 plays that center the Asian American experience, exploring a range of themes that were relatively unexplored at the time, from interracial marriage in Yohen and generational conflicts of mixed-race children in The Wash to closeted gay Asian American performers in Hollywood in Yankee Dawg You Die and violence against women in A Fist of Roses.

In the next episode of the series, we’ll hear about how Gotanda first found his voice as a third-generation Japanese American through music during the emerging Asian American movement, which began at UC Berkeley.

This is Fiat Vox, a Berkeley News podcast. I’m Anne Brice. You can subscribe to Fiat Vox, spelled F-I-A-T V-O-X, wherever you listen to your podcasts. For more episodes, visit our podcast page on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

Listen to other Fiat Vox episodes: