COVID Stories: What is it like to be hearing impaired during COVID-19?

Jenn Stringer, associate vice chancellor for IT and chief information officer at UC Berkeley, talks about how communicating during the pandemic has become easier in some ways and gotten harder in others.

May 19, 2021

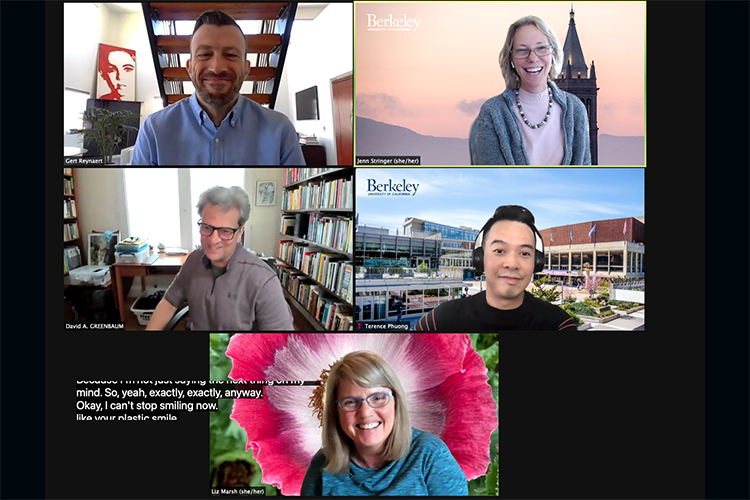

Jenn Stringer (upper right) is associate vice chancellor for information technology (IT) and chief information officer at UC Berkeley. Stringer said that Zoom’s auto-transcription feature has been essential to her ability to hold and participate in virtual meetings. (Photo courtesy of Jenn Stringer)

The COVID-19 pandemic has separated us, but sharing stories about how members of the campus community have been surviving — and even thriving — since spring 2020 can help draw us together. Berkeley News is gathering inspiring personal tales of heartache and triumph related to the coronavirus and will run them periodically. To pitch us your story, send a brief email to [email protected]. Check out the whole series here.

Jenn Stringer, associate vice chancellor for information technology (IT) and chief information officer at UC Berkeley, shares a story in her own words about discovering when she realized she was hearing impaired, the strategies she uses to communicate, and the upsides and downsides, for her, of COVID-19.

I happily lived my life until my daughter was born, unaware that I was actually hearing impaired. My oldest daughter was born when I was 22. My husband came home and he said, “Can’t you hear the baby crying?” And I said, “No.” We were in the other part of the house. This was before baby monitors. I walked into the room and I could hear the baby crying.

So, I went to get my hearing checked out, and it turned out that I was moderately hearing impaired, although dipping down into severe in a number of places. The doctor asked, “Do you have hearing loss in your family?” And I said, “That’s a good question. I have no idea.” I went back and asked my mom, and her response was, “Oh, yeah, your great-grandfather was deaf.” So, it turns out that I must have some sort of genetic predisposition to hearing loss. I started wearing hearing aids and have been an on-again, off-again hearing aid user.

Stringer didn’t realize she was hearing impaired until she was 22 and discovered she couldn’t hear her baby crying. (Photo courtesy of Jenn Stringer)

I am now at a point where I’m in the severely hearing impaired category. But I’ve learned to use a lot of other ways to communicate.

As my hearing got worse, I recognized that I couldn’t take notes anymore in a meeting because I needed to look at people to understand what they were saying. So, I stopped taking notes in meetings, and instead, I paid a lot more attention to looking at people so I could see their mouths and could pay more attention to body language.

I worked at Stanford for 23 years and built a team there. We worked really well together. Then, I took another job, and I went to NYU in 2011. It wasn’t until I got to NYU and was in a meeting where I didn’t understand what was happening or being said when I realized that, at Stanford, I would have turned to someone who worked for me, and they would have repeated what was said. I was inadvertently using my staff as an “accommodation.” I didn’t even realize I was doing it. I don’t even know that they knew that I was doing it. But it was in that moment in New York that I realized, “I am really deaf. This is actually a problem.” That was the first time that I really realized that my navigation through the world was different than people who had better hearing than I did.

So, I went and got a new pair of hearing aids, a better pair. For the first time, I needed to say, “I’m sorry, I missed what you said. Could you please repeat yourself?” Or, “Could you please speak more loudly? I’m having trouble hearing you from across the room.” I just started learning to state what I needed because I didn’t have my compensation mechanism anymore.

Stringer, who has worked on staff at Berkeley since 2013, said she’s looking forward to returning to campus this summer. “I miss being in a room with people and a whiteboard,” she said. “It also means that I get to use my lip-reading skills again.” (UC Berkeley Library photo by Jami Smith)

I got to Berkeley in 2013. I have learned lots of other coping mechanisms, like asking people to speak up. I also will move around in a room, so that I can see people speaking. I’ve learned that if I need to stand up, it’s OK. And if I need to stand up and move so that I can lip-read somebody to understand what they’re saying, I just do that. I always sit up front. I don’t go to movies anymore. I’m a theater-goer, but I have season tickets and always ask to be in the front, so that I can see. That’s how I’ve sort of navigated that in-person world.

When I got the CIO job in June 2020, it was right in the middle of the pandemic. Zoom is awesome, because I get to see everybody, and I don’t have to stand up. And they created this amazing auto transcription, which, for me, is a lifesaver.

But on Zoom calls, when people were in other settings on campus, for example, where they had to have a mask on before the auto transcription started, I actually would ask for a back-channel chat, and I still do. Often, if I’m in meetings, I will ask a colleague if I don’t understand something. Particularly at high-level meetings, I will ask, “Will you be my chat partner, so that I can understand?”

But I will say that I felt like I had to continually raise the concern about the hybrid environment, where they wanted to bring students back to the classroom, but everybody would be masked. For people with hearing impairments, or people for whom English may not be their primary language, they are looking for all kinds of clues to make meaning. And I’m sure that a lot of them do the same: depend on other cues that have a lot to do with facial expressions. It’s just an incredibly inferior experience when somebody is covered like this, and you really can’t understand them.

When Stringer was diagnosed with breast cancer over the summer, it was the first time during the pandemic that she had to leave her bubble. (Photo courtesy of Jenn Stringer)

I was diagnosed with breast cancer this past summer, and that was the first time I had to go out of my bubble. We were really locked up. You know, I grocery shop, but you don’t really have to talk to people when you grocery shop. I wasn’t dealing with a lot of people in mass because I wasn’t going outside of my house, and I had people on-scene. So, my life was awesome.

All of a sudden, I had to navigate a world where I had to go into a health care facility, speak to physicians and nurses using language that was, you know, not in sort of the normal lexicon of meaning-making. And my husband couldn’t go with me because of COVID. They always tell you to bring somebody in with a doctor when you’re getting bad health news, right? Because you need somebody else to hear. And that was completely unavailable because of COVID.

So, I actually started saying to my care providers, “Look, I’m hearing impaired. I’m wearing my hearing aids, I turned them up. You’re just going to have to speak really slowly and loudly for me to hear what you’re saying. And I may ask you to repeat things, and I may actually even ask you to spell things or write them down, so that I can understand my care. And if we can have teleconferencing appointments, that’s actually better for me than coming in.”

There are clear masks that have clear plastic on them, and I actually did get some sent to me to use if, like, my mom stopped by, and we went for a socially distanced walk. I tried the plastic mask. It wasn’t great. It fogged up, and it wasn’t fantastic. So, in the end, it was easier just to tell her to talk really loudly into my right ear, which seems to be better than my left. And I will say that now, with some of the face shields and vaccination, when I’ve gone to clinics, they’re much more willing to just wear a face shield, so that I can read lips, and it’s better.

I am really looking forward to returning to campus this summer! I miss being in a room with people and a whiteboard. It also means that I get to use my lip-reading skills again. I haven’t had to use those skills as much with Zoom’s auto-transcription.

That said, my own IT organization is embracing flexibility for working remote. We have talked a lot about the challenges of holding meetings where some people are virtual and some people are in-person. We have come to the conclusion that hybrid meetings, by their very nature, often exclude people who are attending virtually: They can’t see facial expressions or gestures and body language, and even if they have great hearing, they often can’t hear sidebar conversations. But it also works the other way: If there are only two people in a meeting room and 20 people online, the people in the room might not be able to participate in chat.

So, our organization has agreed that if even one person is going to be remote, we would hold the meeting via Zoom to provide equity of experience. I see this as an opportunity for us, as a campus, to leverage what technology has to offer and to rethink some of our practices and social norms, so that we can be a more inclusive institution.