Very big changes are coming very fast to the American workplace

“We are at a major inflection point,” says one Berkeley scholar

July 1, 2021

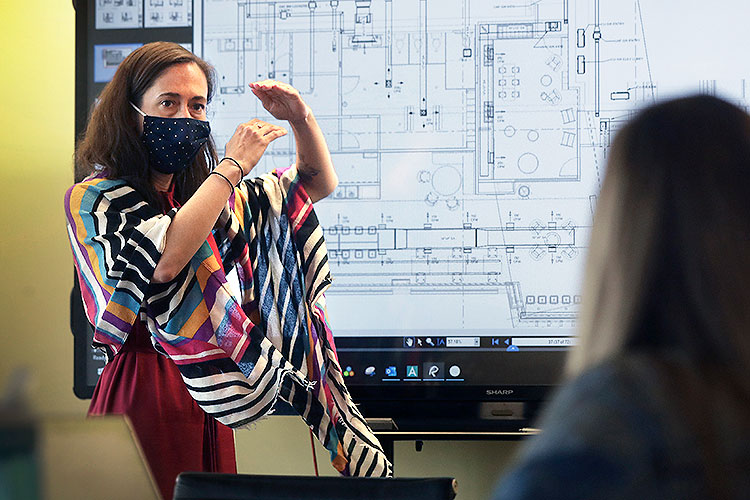

After 16 months of working at home during the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of Americans are returning to the office. UC Berkeley business experts say they will find broad changes in work schedules and routines — and often changes in their own relationship to work. (AP photo by Steven Senne)

Going to work used to be so simple. Across a span of decades, in organizations large and small, American white-collar workers by the millions would wake up in the morning and get to the office by 8 or 9. They would leave at 5 or 6, perhaps later if they were on deadline with an important project. It was like clockwork.

Suddenly, however, that model seems outdated, if not archaic. In a series of interviews, Berkeley scholars who study work and management say that as the COVID-19 pandemic eases, American executives and office workers are emerging into a new and unfamiliar world that may have broad benefits for both.

More freedom to work from home? Check. Higher productivity and customer satisfaction? Check. And for those at the office, improved space for collaborating and better options at lunchtime? Check and check. But with these changes, Berkeley experts say, the format of work that prevailed for a century, pre-pandemic, may go the way of horse-drawn carts, wall-mounted telephones and bike messengers.

Many workers have a new understanding of what they need from their employers, and they’re ready for change. And many top businesses are embracing the changes, too. Not only might they be important to worker health and well-being, but they augur other sorts of innovation, not to mention higher profits and greater impact.

Laura Kray (UC Berkeley photo)

“Organizations and people are slow to change,” said Laura Kray, professor and faculty director of the Center for Equity, Gender and Leadership at the UC Berkeley Haas School of Business. “But we’re a couple of decades into this century, and then the pandemic hits, and it has forced us to change. We’ve all learned to use Zoom. We’ve acquired new skills. Now we know that we can be productive even if we’re not in the office or on campus.”

And it’s not the pandemic alone that is driving this change, added Berkeley Haas senior lecturer Homa Bahrami, an author and international business adviser on leadership and organizational flexibility. The historic political turmoil of recent years, the social protests against government mismanagement, police violence and racism, all contribute to a climate of change that holds potential for transformative innovation — and for myriad challenges.

Homa Bahrami (UC Berkeley photo)

“We are at a major inflection point,” Bahrami said, “and not just socially, or in the political arena. From the vantage point of business, several forces have combined to create a new reality.”

Just after the pandemic forced the first broad shutdowns of work, travel and other human activity in March 2020, Berkeley scholars forecast that we were embarking on a vast experiment in the nature and conditions of work.

The subsequent months were tragic for millions of people, and disconcerting and disorienting for tens of millions of others. Now, 16 months later, we’ve learned a lot, but we remain on a road to an uncertain destination.

In business jargon, Bahrami said, there’s a term for it: the ‘VUCA world’, an acronym short for volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity.

The one certainty? Change — rapid, potentially transformational change.

‘Work has to fit my life’

For much of the 20th century, working life was focused on the office. Neighborhood commerce and transit systems were built to support it. Even as portable personal technology improved, the Internet evolved and social media were born, we clung to the old conventions. When people work from home, we assumed, motivation suffers and productivity falls.

The pandemic has changed all of that, the Berkeley experts said.

“In the world of yesterday, we organized our lives around work schedules,” said Bahrami. “I’ve got to have somebody come and take care of my baby. If I’ve got young children, I’ve got to drop them off at school. But I’ve got to make sure I’m at work for X amount of hours.

“Now, it’s the reverse. Work has to fit my life.”

Cristina Banks

Cristina Banks directs the Interdisciplinary Center for Healthy Workplaces, a global research center at Berkeley, and she’s been tracking the real-time evolution of work since the pandemic began. The most obvious change, Banks says, is that people have had the experience of working from home — no rigid hours, no commute, less exposure to office politics, racism and sexism. And many prefer it.

Banks cited a February 2021 survey by the business consultants firm of Willis Towers Watson showing that, in the midst of the pandemic, 57% of employees were working remotely, compared to 11% pre-COVID. A projected 37% will still be working from home at the end of this year.

New research by the Society for Human Resource Management found that 52% of workers surveyed would prefer to work from home, full-time and permanently.

Why have many business leaders not objected? Banks pointed to a report by the McKinsey consultancy firm, released last month: Productivity hasn’t fallen during the pandemic, according to a survey of 100 business executives; in fact, many say it has risen. Now, nine of 10 organizations plan to shift to a hybrid work model that allows employees to split time between home and the office.

UC Berkeley, for example, has developed extensive plans to let many staffers continue with hybrid work schedules.

Cameron Anderson (Photo by Jim Block)

“I would guess that working life has permanently changed,” concluded Haas Business professor Cameron Anderson, an expert in leadership and team dynamics. “Employees and companies are discovering the value in remote work and they are realizing that old fears about it are wrong. … Employees do not disengage and lose motivation while working from home in the way that many employers feared.”

In Bahrami’s view, the “volcanic eruption” of social change and business transformation coincides with the retirement of a generation of baby boomers and the rise of late millennials and early Gen Z “zoomers” into the workforce.

Younger workers are driving a host of changes, including a “digital acceleration,” she explained. “The generation that’s grown up with information at their fingertips is not the same as the generation that grew up using index cards in a library.”

For women, a difficult set of workplace trade-offs

Women have experienced the pandemic differently than men, the Berkeley experts say, and their return to work is likely to take a different path, too. Some of that may result from their roles as primary caretakers for children or older parents.

Many women found that the COVID-19 lockdowns fundamentally changed their relationship to work, Berkeley business experts say. Some welcomed the extra time to care for children. But women, people of color and LGBTQ people may find that working from home provides some protection from a hostile work environment, they said. (AP photo by Ted S. Warren)

“I know women who are mothers with children at home and they really want to get back to campus because they have more space to do their work,” Kray said. “And then there are just as many who say, ‘This is so much better and I want to stay working from home.’”

Bahrami offered anecdotes about women who are leaving lucrative, high-level jobs for the flexibility of consulting work.

“One person I know used to work for Google and now she’s setting herself up as a contractor,” Bahrami explained. “She’s saying, ‘I don’t want to be a full-time employee. I’ve got two young children, and I found that the COVID time has given me enormous flexibility. … I’ve saved on my commute. I’ve had childcare problems, but now I’m spending quality time with my kids.’”

“One person I know used to work for Google and now she’s setting herself up as a contractor,” Bahrami explained. “She’s saying, ‘I don’t want to be a full-time employee. I’ve got two young children, and I found that the COVID time has given me enormous flexibility. … I’ve saved on my commute. I’ve had childcare problems, but now I’m spending quality time with my kids.’”

Kray, however, sees another factor at work on campuses and in offices: Women, people of color, LGBTQ people often have to endure a work environment that is unwelcoming and sometimes hostile, and they may find a better work environment at home.

As the pandemic lockdowns ease, “women and underrepresented minorities are more likely to say they want to stay away,” she said. “What does that tell us about the culture? By being away from campus or the office, some feel as though they have a little bit more control over their environments.”

The extraordinary challenge of managing extraordinary change

As the old conventions of office work fade and worker expectations shift, leaders and managers have a complex assignment: They must turn challenge into advantage, profit and impact. But, the Berkeley experts say, it’s not clear that employers are ready.

For example, a hybrid work schedule seems like a great innovation. But it opens a Pandora’s Box of uncertainty. Banks detailed some of the challenges:

If half of a company’s staff on any given day is working from home, how does that change needs for office space? Do we keep our individual desks? And if not, what sort of logistical feats will be required to keep them free of lunch crumbs and sanitized to prevent illness?

Working from home may raise productivity, but what strategies are needed to keep employees connected and to prevent burnout?

Do workers have some base need for social stimulation at work? And if so, what’s the best mix of working at home and at the office?

And what if the answers are different for different teams? Or for different personality types?

With skilled workers in high demand, many employers want to make the office environment homey, and even fun, Berkeley business experts say. (Wikimedia photo by Steelcase)

Inevitably, Banks said, planning for a new era has to go beyond the question of how many days an employee is allowed to work from home. Some employees may have lost family or friends to COVID. Others may be suffering delayed emotional or psychological impact from stress and isolation.

“The organization has to provide for the care and support of its employees coming back to work,” she said. “Leaders have to be sensitive to the fact that things have dramatically changed with their employees…. There’s trauma.

“There should be a strategy that the company or organization puts together to continue to build the culture, to create the diversity and inclusion, to stimulate innovation, to build a sense of belonging and connection and social cohesion.”

Banks and other Berkeley experts said that strategy could have many facets: Structuring schedules to encourage in-person cross-pollination among different teams. Extra support for workers with kids or elderly family members. Arranging social events and better food options.

A company or organization that doesn’t deal with these issues is risking extensive turnover and diminished profits, the experts said. But Banks worries that companies are not ready for this new reality.

“The whole idea of looking at your workforce as subsets of people who would really grow together, and benefit, and enjoy being in the workplace together, and advancing the business — there’s just not a lot of conversation on how to do this,” she said.

Workplace experiments could continue for months — or longer

In the VUCA world, some lag time might be inevitable. Work has been transformed, and changes continue to come unpredictably. Still, the signals suggest that employers are scrambling to adapt.

According to the Willis Towers Watson report, 93% of those surveyed say employee mental health will be a priority for the next three years, at least.

Bahrami said U.S. tech giants are choosing different paths that reflect their corporate and creative cultures, ranging from a return to full-time work at the office to full-time remote work.

In such a climate of uncertainty, one long-standing commitment remains essential: For organizations that want to accommodate change and keep their employees connected, creative and happy, enhanced communication will be essential.

“People misread each other more often in email, and miscommunication and even conflict are more likely to emerge,” said Anderson, the Haas Business leadership expert. “Nothing beats the richness of face-to-face interaction for the clearest communication. Face-to-face also makes it easier to build trust and rapport, where people feel more comfortable with each other and that they are on the same team.”

Undoubtedly, communication will be one area for continuing trial and error. And there will be others, from scheduling and reimagined workflow to new training for workers and managers. Such experiments are likely to go for months, the experts said, as leaders and staff members work to harmonize and fine-tune the new workplace.

The pandemic has been a crucible for change, they agree, but exactly where that change will take us won’t be known for months, and perhaps years.