As wildfire season advances, so does major DIY air purifier effort

Rooted at UC Berkeley, the Common Humanity Collective so far has built 1,200-plus air purifiers for Bay Area residents most vulnerable to smoky skies

October 28, 2021

Miguel Simpson couldn’t believe his luck. On his way to Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church in West Oakland on a recent Sunday, he saw dozens of free air purifiers being distributed outside a nearby vegan café, in the middle of wildfire season.

“Wow! I felt, wow! I live in a hotel and have to keep my window open for air, and smoke was coming in” during summer 2020, he said, when about 25 California fires were burning. So, Simpson eagerly accepted the freebie — one of 1,200 do-it-yourself air purifiers assembled so far by the Common Humanity Collective, a Bay Area mutual aid organization — and then joined the effort, too.

“They said, ‘Come on down, help us out, and get as many (purifiers) as you want. Spread them out to other people. I said, ‘That’s cool,’” said Simpson, adding that he doesn’t know anyone with an air purifier in his downtown Oakland neighborhood.

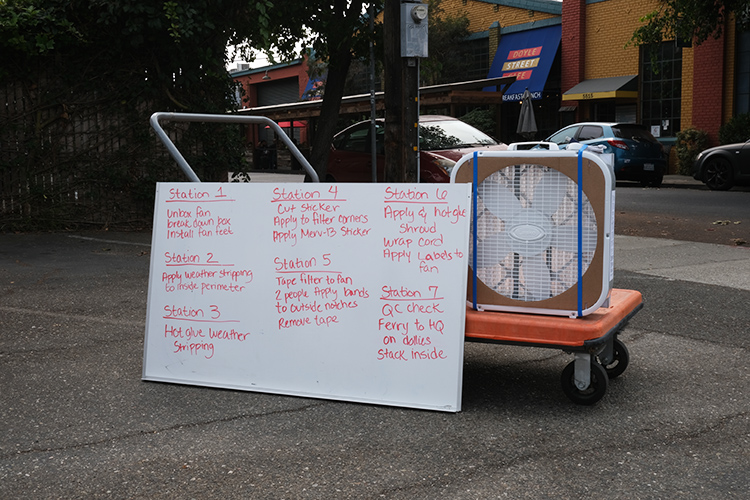

At the start of a Sept. 25 Common Humanity Collective event in Emeryville, box fans are unpacked by volunteers before being outfitted at a series of stations with filters, turning them into air purifiers. (Photo by Christopher Gee)

The DIY air purifier is the latest project at the collective, which was launched — before it had a name — in March 2020, near the start of the COVID-19 crisis, by UC Berkeley graduate student Abrar Abidi and campus research assistant Yvonne Hao to help make life safer for those most at risk in the pandemic.

This fall, as wildfire season continues, nearly 70 volunteers show up every other Saturday at an Emeryville parking lot on Doyle Street to attach MERV-13 filters to basic 20-by-20-inch, three-speed box fans with PVC foam weather stripping, hot glue and large, elastic silicone bands. So far, the collective has given 970 air purifiers to local low-income residents whose neighborhoods have both high air quality index (AQI) readings and high asthma rates.

“More than anything we’ve done in the past, the DIY purifier project has blown us away,” said Abidi, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in molecular and cell biology. “We’ve been doing this every other week since July. There’s just so much momentum. People show up, get to know each other, self-organize into different stations, and joyfully assemble between 120 and 200 purifiers in a few hours. It’s astonishing to see, and it unfolds so organically.”

Assembly of the Common Humanity Collective DIY air purifiers is a seven-step process. Volunteers work at various stations, passing their finished work on to the next table. (Photo by Emiko Moran)

The collective’s purifier costs about $35 to build, can be made in 15 minutes, and its design is an improvement over typical DIY box fan-and-filter versions. Written instructions, photos and a video for those who’d like to make their own are on the collective’s website.

From sanitizer to masks to air purifiers

During the early days of the coronavirus, Abidi and Hao, now in medical school, worked up to 20 hours a day, with financial and lab assistance from colleagues on campus, to make hand sanitizer in the fume hoods of evacuated campus labs. They produced 7,000 gallons, enough to distribute, without charge and with help from a few dozen volunteers, to 120,000 people in shelters, jails, low-income housing and nursing homes.

Then, last winter, the newly-named Common Humanity Collective — swelling into a busy mutual aid organization of more than 250 Bay Area volunteers — designed, built and distributed nearly 60,000 free submicron face masks. Boxes of masks even were sent to Central Valley farmworkers, Louisiana hurricane victims and the Navajo Nation in Arizona and Utah.

A father and his youngster affix a cardboard shroud, made from the box fan’s packaging, to the front of the fan. It will block inefficient air currents at the corners, increasing the device’s efficiency. (Photo by Sean Gillane)

Alumnus Chris Gee, a Berkeley Ph.D. recipient in plant and microbial biology, designed the collective’s no-sew, 85% efficient mask that can be made in five minutes or less from an inexpensive shop towel and a nanofiber filter. Then, he pivoted to creating a homemade air purifier.

“The transition point came when vaccines arrived, and COVID seemed on the run,” said Gee. “During that lull, we took stock of our budget and our future to decide whether to continue or dissolve the collective. But fire season was expected to be really bad again, … so air purifiers became the next manifestation of hand sanitizer and masks. Our motivations are the same: We’re trying to meet people’s basic needs, while building connections between the people contributing and receiving.”

Trying to find the most affordable, yet effective, materials for an air purifier, Gee ordered a few test filters from Filti, an HVAC filter business in Kansas City that he discovered last year, and tried out different ones by attaching them to an inexpensive box fan.

Two volunteers place foam weather stripping along the perimeter of a box fan’s frame. This creates a tight seal between the fan and filter to reduce leaks that would allow dirty air to bypass the filter. (Photo by Emiko Moran)

“I locked myself in my bathroom, lit incense to fill the relatively small space with smoke, ran the filter to clear the smoke, and recorded how long it took for the smoke to clear,” he said. “In consultation with the Filti reps, I arrived at a MERV-13 filter, which is a good balance between trapping small particles, while still allowing air to go through.” The filter is about two inches thick and is not washable, but Gee said it should last an entire fire season.

A number of volunteers studied data maps of the East Bay and found an overlap between areas where low-income people live and where there is a high AQI value; they also checked for areas with high asthma rates. Then, they discussed where to distribute the purifiers. So far, they’ve been given away mostly in the East Bay, but a partner organization, Mask Oakland, rented a U-Haul recently and took more than 130 purifiers to Reno and Placerville, when the AQI there hit the 500s.

So far, the Common Humanity Collective has assembled 1,200 air purifiers and, with luck, will continue to raise enough donations to buy supplies to make many more. (Photo by Christopher Gee)

The group also wondered how quickly to distribute the air purifiers. “We wondered, ‘Should we be trying to distribute them as fast as possible, or wait until the crisis arrives and respond to requests for purifiers as they come in?’” said Abidi, adding that the decision was to do both.

But the collective is on edge about how much longer it can afford the $2,000 rent, plus utilities, insurance and other costs for its Emeryville storage space. And funds are running out to buy more materials to make the air purifiers.

“The cost is weighing a lot heavier on our minds,” said Gee. Previously, the collective had used a conference room on campus as storage space, but when in-person instruction resumed this semester, the space was no longer available. The Bay Area chapter of the Sunrise Movement, a youth-led climate mobilization group and a strong ally of the effort, recently held an emergency fundraiser to contribute toward keeping the collective afloat.

This step in building a homemade air purifier is easier with two. An elastic band is used to attach the air filter and allows it to be easily removed and replaced, as compared to taping or gluing the filter directly to the fan. (Photo by Christopher Gee)

Gee said he hopes people will retain some of the perspective they had early in the pandemic, when many made masks for themselves, as well as for others. Later, “the rush to regular life swept that sentiment aside,” he said. “We want to challenge people to retain some of that perspective for another crisis” — protecting the vulnerable from dangerous, smoky skies.

Despite Northern California’s recent atmospheric river, weather experts say it remains to be seen if the wet weather will affect the drought plaguing the state and elsewhere in the western U.S., and that the rain and snow that fell on California’s dry landscape is likely to evaporate or absorb into the soil.

Volunteers use hot glue to secure the foam weatherstripping, making it able to withstand future filter changes. (Photo by Christopher Gee)

The feeling is mutual

On Saturdays in Emeryville, Emiko Moran, a staff member in Berkeley’s Department of Social Welfare who previously made masks for the collective, is an air purifier DIYer. She said she’s painfully aware that buying one “on the market for $100 to $200 is not an option for many folks.”

She enjoyed the ease of assembling masks at home from 40-mask kits she picked up from a Common Humanity Collective coordinator in her neighborhood. But she said she’s found it rewarding to work in person, alongside others, meeting people she otherwise might not.

“I showed up, I didn’t know anybody at the first one,” said Moran. “I brought a friend with me. There was a friendly person at the sign-in table, potluck snacks, music playing. It was an inviting community event that made it easy to feel there was something you could contribute, and that you’d want to do it again.”

The Common Humanity Collective is a mutual aid organization. Mutual aid is an act of solidarity against a common struggle, with communities organizing to help each other. It fosters the formation of sustained networks among neighbors and organizes to change unfavorable political conditions. (Photo by Emiko Moran)

Free childcare and food for volunteers “lowers the barrier to entry for new people to get involved,” added Genean Wrisey, a union organizer in Oakland who helps drive volunteer turnout for the collective and plan distributions. “The only way to build power is through solidarity, and that only happens if people have relationships with each other and care for one another.”

Michi Taga, a Berkeley associate professor of plant and microbial biology and the mother of two young children, also attends the Saturday “builds,” where volunteers — from high schoolers to retirees, from an ex-Black Panther to a former missionary nurse — converse as they work.

“I didn’t have any experience with mutual aid before,” said Taga, “so this experience has made me more aware of the idea, and it’s not a new idea — communities helping each other.”

Air purifiers and supplies are kept in a former dance studio being rented in Emeryville by the Common Humanity Collective. Every other Saturday, the air purifiers are constructed across the street, in a vacant parking lot. (Photo by Abrar Abidi)

Rather than a top-down, paternalistic response to a crisis, mutual aid is an act of solidarity against a common struggle, with communities organizing to help each other. It fosters the formation of sustained networks among neighbors and organizes to change unfavorable political conditions.

The collective partly distributes purifiers through local partner organizations with shared aims and values, such as the Sogorea Te Land Trust, Tenant and Neighborhood Councils, and Critical Resistance. The remaining purifiers are distributed through volunteer teams that visit at-risk, previously mapped East Bay communities, set up a base outside a volunteer’s home, and go door-to-door. As they talk with people and hand out purifiers, the volunteers build relationships, learn about local issues, and invite families to join the next build and then return home with more purifiers to distribute directly to their neighbors.

Sometimes, those on the receiving end decide to participate in the effort.

Asians 4 Black Lives, a community group that partners with the Common Humanity Collective, loads its truck with air purifiers off the delivery line and heads out to distribute them. (Photo by Abrar Abidi)

Eric Warner, newly in an apartment in Oakland after living in transitional housing, picked up a free air purifier after church on the same day Simpson did. Members of the collective invited Warner to help his community by joining the air purifier project, and he did.

“It was beautiful,” he said. “We had pizza, everyone was working together, and I gave a few purifiers I built to my uncle in East Oakland. He loves them.”

As for Simpson, he plans to attend his second DIY event with the Common Humanity Collective on Oct. 30, his birthday.

“I don’t mind doing something like this on my birthday,” he said, “because God gave me another year to help people out.”