‘Day of Rage,’ film coproduced by Berkeley alumna, on Oscar shortlist

The 40-minute short documentary on the Jan. 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riot is the first Oscar-honored film from the New York Times' newsroom, where Willis, a 2019 grad, is on the visual investigations team.

January 26, 2022

Haley Willis, a 2019 graduate of UC Berkeley, is on the visual investigations team at the New York Times and a co-producer of Day of Rage, a documentary about the 2021 U.S. Capitol attack. (Photo by Earl Wilson/New York Times)

For the first time, a New York Times documentary made in-house, Day of Rage: How Trump Supporters Took the U.S. Capitol, is shortlisted for an Oscar for Best Documentary Short Subject. The 40-minute graphic, fast-paced film was created by the Times’ award-winning visual investigations team, which includes UC Berkeley alumna Haley Willis, who graduated in 2019 with degrees in sociology and media studies.

Willis, a visual investigations reporter and video producer, coproduced the film, a meticulous analysis of thousands of cellphone videos, police bodycam footage, internal police radio traffic, and video from Capitol security cameras about the 2021 U.S. Capitol attack. The result of the six-month project is the most complete chronology to date of what happened that day, and why. The film has been streamed more than 8.5 million times.

Finalists for the March 27 Academy Awards will be announced Feb. 8. Day of Rage already is a finalist in the 2022 duPont-Columbia Awards, as is American Insurrection, a 90-minute documentary about the threat posed by militia groups, white supremacists and other extremist groups produced by Berkeley Journalism’s Investigative Reporting Program, PBS “Frontline” and ProPublica.

Berkeley News recently talked to Willis, who learned open source investigation skills as a member of Berkeley’s pioneering Human Rights Investigations Lab and was hired by the Times in December 2019 after first working as its sole visual investigations fellow. She spoke of how the film was put together, which scenes she can’t forget, and her reaction to the Oscar buzz.

Berkeley News: What prompted the New York Times to create a documentary on the Jan. 6, 2021, siege of the U.S. Capitol?

Haley Willis: The idea came up the day of the attack. It was clear to us from the beginning that this was something our team, based on our expertise, was in a position to cover. Obviously, it was very visual. A lot of people were streaming the riot live. Thousands of video clips eventually were uploaded onto social media platforms, from countless angles.

We knew we could clear the smoke and show what really happened that day, to tell the broadest story, from every given point in the day. It was a very chaotic event, as seen from a lot of different sides, by a lot of different people — including rioters, journalists, lawmakers and law enforcement. On the visual investigations team, we unfortunately cover a lot of graphic content, things that are extremely difficult to watch, including the killing of George Floyd. Still, the footage that came out of this (siege) really stuck with us. I would have dreams afterward about the people there that day at the Capitol. I would wake up and think, “Oh, they broke into the building at another location that we missed!” — and then would realize I had actually just dreamt that up.

We also knew the attack would be followed by attempts to rewrite what happened — especially by those who perpetrated the big lie that drove the violence of the day — but that our film could be a decisive account of what actually happened. It would stand on its own and speak for itself, like a historical document.

We’ve already had some history teachers say, “I’ll show this to my students.” Outside of some expected negative responses, we’ve overwhelmingly heard that the film lifted the fog surrounding a very chaotic event — one that is clearly definitive in American history. That’s all we could ask for.

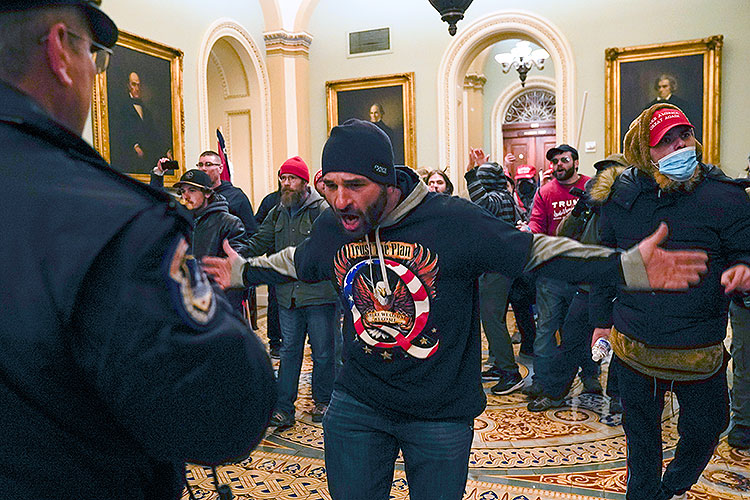

Day of Rage is shortlisted for an Oscar for Best Documentary Short Subject. Oscar finalists will be announced Feb. 8, and the Academy Awards are on March 27. (New York Times image)

What were some of the sources of the videos you obtained?

A variety of places, obviously social media —Twitter, Facebook, Twitch, Periscope, YouTube, right wing platforms like Parler, where many rioters were uploading footage themselves. We also had a freelancer filming at the Capitol for the New York Times, and New York Times photographers inside.

We obtained video from security cameras inside and around the Capitol. We attempted to do information requests from Capitol Police for radio communications and video, which we weren’t able to secure. But Congress investigated (the siege), and key security camera footage was published during Trump’s impeachment hearing; the House committee shared what they had collected with the media.

We also reached out to several people who were there that day, including legislators and their staff, such as Nancy Pelosi’s staffers — who shared audio from when they were hiding in her office — and freelance journalists and other witnesses.

But most of the footage in the film is from the perspective of the rioters, and it all was collected through open sources. We thought it was important to allow people to watch from that perspective. Of course, we wanted to put these videos into context and tell the entire truth surrounding them. But there is value in hearing what these people are saying and feeling as they’re carrying out this attack. It tells a very important story about what, and who, motivated them to act. These were the people that were filming during some of the most violent moments of the day — for example, the deaths of Ashli Babbitt and Rosanne Boyland.

With such a wealth of material, how did the team make sense of it all?

A lot of people at the Times contributed to this. Ultimately, there were five primary producers who collected and verified the materials, along with our two directors. We put the evidence into a massive spreadsheet with a timeline. Every time we got something new — a tweet, a radio communication — we’d put it on the timeline and ask, “What time did this happen?” “What does it show?” That was a huge part of the producers’ work, and many more reporters across the newsroom contributed their expertise — for example, our colleagues in the D.C. bureau. We also had a team of fantastic editors; this was a feat of editing, and I’d never seen anything like it. They are the ones who turned that spreadsheet into a film that could make sense to an audience.

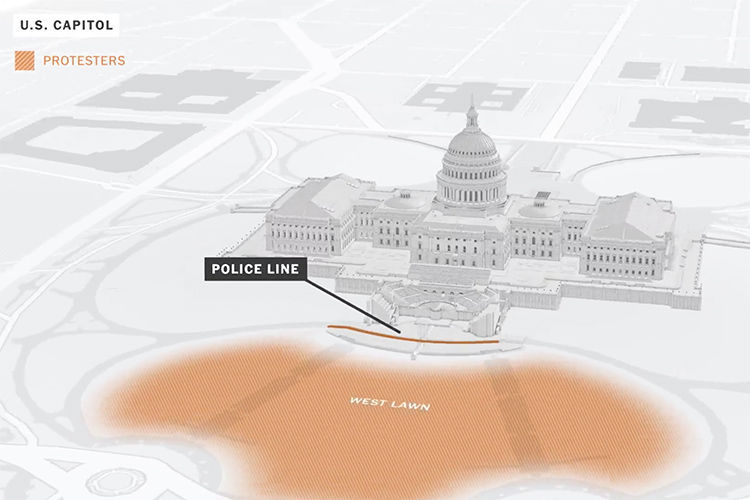

We also had our incredible animator on the visual investigations team. Early versions of the film, before the animation, were hard to follow. We knew we didn’t want to overanimate it, but the maps and the 3D models of the Capitol building became invaluable, in terms of giving viewers space to breathe and reorient themselves between the footage. This is really intense video to watch, which takes a toll and can make it hard to get the bigger picture without those orienting moments.

We carried out interviews to make sense of the various threads we were putting together — for example, with former law enforcement officers who could help break down the lingo we were hearing in radio communications, or in speaking with the Capitol architect to understand what different breach points in the building were.

What made our work so much harder is that we were all working from home and still are, taking precautions with COVID. Near the end of production, when we were all vaccinated, we went in a few times to the office to get on the same page and watch the footage together. Our work on this film is really a testament to our collaboration remotely.

What facts do you think Day of Rage establishes that otherwise couldn’t be as easily understood?

The film gives the perspectives behind the riot, why it happened. There were times that Trump would tweet, for example, about Mike Pence choosing to certify the election, and five minutes later, the rioters were saying the same things he had, feeding off of what they were hearing from him. They were driven by disinformation — not just to come to D.C., but throughout the entirety of that day.

Organizing the evidence in the way we did, we began to get a very clear picture of the many domino effects in play. While it was evident there was no leader among the rioters that day, we saw a clear pattern of small, organized groups taking actions that would incite the much larger mob of individuals into violence. We also started to understand how the rioters were inspiring each other. On one side of the Capitol, they would be discussing how the group had broken in on the other side, and that they should do the same.

Parsing through these types of details led to really pertinent discoveries. For example, we realized that a delay in shutting down the House may have contributed to the vitriol that led to Ashli Babbitt’s death, as rioters came almost face-to-face with the (government) representatives they had been attempting to reach. All of these are small pieces to a very large puzzle, and I think the film takes on a lot in attempting to put that together.

An animator on the New York Times visual investigations team created maps and 3D models of the U.S. Capitol to help viewers orient themselves to the building and where events of the day took place. (Image by Drew Jordan/New York Times)

Are there certain scenes that stick in your mind?

A huge one is just the level of violence and the incongruity I felt watching it unfold: You hear the rioters say to the police, “We support you, we’re the ones who back the blue. We’re on your side,” as they’re attacking them with an American flag. There was the level of entitlement, hearing people say, “The president invited me here,” and they genuinely believed that, that the president invited them there. And I think seeing how strongly these people felt they were doing the right thing is disturbing.

Outside of the general intensity of the violence and disinformation, there are small moments that stick with you. I remember one scene, where a rioter is talking to a Black police officer. He’s trying to tell the officer about what the country was like when he grew up in the 1960s, to which the officer responds that his people were dying every day in the ‘60s. The man then says that there is no racism in America, to which the officer very poignantly replies, “Maybe not in your world.”

At Berkeley’s Human Rights Investigations Lab, you learned to prioritize your well-being when working with graphic content. Did that help with this project?

Absolutely. And we’re fortunate, on the visual investigations team, that despite the fact that we cover difficult content, we are also fostering a healthier model for journalism, which is to work on it with others, extremely collaboratively. You always have to contend with news and deadlines, but our team, given what we focus on, has open conversations and awareness about the need to step away and do something else. We check in with each other, talk about it, help each other pick up the slack.

Fortunately, I got to do other work while we were producing the film. We were publishing scoops we found along the way, other Capitol-related stories, such as one focusing on the specifics of the police response. I was able to produce stories on an insurgent attack in Mozambique and another on police violence against protesters in Myanmar.

One thing I’ve really picked up in New York, which is great for my mental well-being, is that I bike a lot. I had a bike in Berkeley, but probably rode it twice. Here, a close group of friends and I bike together, and bike all over the boroughs, to New Jersey, Long Island. There’s so much to explore in New York.

I feel I’ve seen a lot through biking, and exercise is good for resiliency. Even in the winter, we still bike. Last weekend, I went on a bike ride with friends, and we got caught in the snow on the way back, so we biked slowly and then wound up walking our bikes the rest of the way.

What’s your reaction to Day of Rage being shortlisted for an Oscar?

Given we’d never done this before, released a film on the visual investigations team, we didn’t go into it expecting this. I knew the team was doing great work and was grateful to be part of it, but there’s no way I would have guessed this might happen.

Once we realized what the film was shaping up to be, a documentary, our director started talking about the Oscars. But I was completely shocked that we were shortlisted and, of course, happily surprised — seeing the incredible films we are up against, and that ours is being well-received by people. It’s not about the award. More so, it’s that we succeeded in producing something that is a convincing, definitive account that people turn to for the facts, and it’s being recognized for that.

I’ve been joking that, if the film is a finalist, the New York Times should rent us a party bus so we can go to LA. I’m sure that would be great for resiliency, too.