Why the story of the United States needs to be challenged

Critical ethnic studies expert Dylan Rodríguez joins a Berkeley panel on the lasting impacts of U.S. violence and colonization in the Philippines

April 12, 2022

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Philippine-American War was billed as a “friendly colonialism,” said UC Riverside professor Dylan Rodríguez. This image depicting the Battle of Balangiga, in which thousands of Filipinx civilians were killed by American troops, shows a different narrative. (Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons)

As the world watches the war in Ukraine, predicated by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s thirst for conquest, United States leaders have referred to the violent killing of innocent civilians as “criminal and evil.”

But for UC Riverside media and cultural studies professor Dylan Rodríguez, the U.S. still has a long way to go in acknowledging its own history of colonial violence, particularly the killing of hundreds of thousands — potentially millions — of people during the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), an event in history that is often ignored.

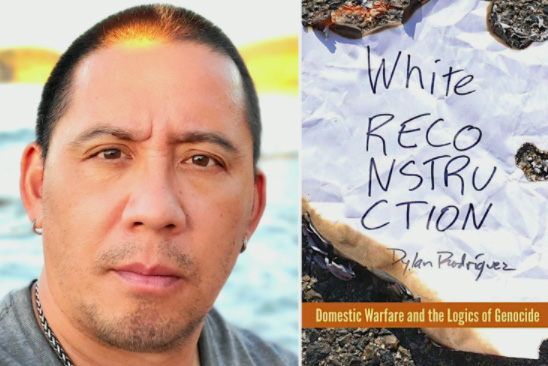

(Image courtesy of Fordham University Press)

“They exterminated entire villages, including elderly people, children and everybody in between. These were war crimes, and the U.S. military was unapologetic and proud of its actions,” said Rodríguez, who also is a UC Berkeley alumnus with a PhD in ethnic studies. “The narratives that valorize the U.S. as some kind of democratic ideal are fraudulent. … It has been over 100 years, and the United States has still not acknowledged this genocidal conquest.”

Rodríguez joined a Berkeley panel of Filipinx scholars April 14 on Zoom to discuss the lasting impacts of the Philippine-American War and the many ways United States imperialism continues to affect Filipinx people in the U.S and the Philippines.

A first-generation Filipinx American, Rodríguez has delved into the nuances of Filipinx community and colonial history for over 20 years. His most recent book, White Reconstruction: Domestic Warfare and the Logics of Genocide, won the Frantz Fanon Award for Outstanding Book in Caribbean Thought and explores how the political and institutional use of diversity, equity and inclusion helps create a new breed of “multiculturalist white supremacy.”

Berkeley News recently spoke with Rodríguez about the importance of challenging America’s false narratives and how academics can help to decolonize research.

[This interview was edited for length.]

Berkeley News: Hundreds of thousands were killed during the Philippine-American War. Some historians believe it to be in the millions. Why do you think this type of brutal violence in history stayed unacknowledged for so long?

Dylan Rodríguez: It’s a misnomer to call it the Philippine-American War. The first point of contact between the two countries, in the late 19th century, is a point of conquest. It’s not war. It’s not diplomacy. It’s not occupation: It’s conquest.

Most historians acknowledge that it was the trans-Pacific extension of Manifest Destiny. Once the conquest of the American hemisphere reached California, the question was: Where does the conquest move now? Well, it moves to the Philippines.

For a long time, the historical narrative was that the U.S. benignly occupied the Philippines, and it was a relatively friendly relationship that brought free public education, state institutions that were legitimate and a proctored transition into modernity. This whole notion of friendly colonialism.

American medical workers are carried on the backs of Filipinx men across the Davao River in the Philippines during the American occupation in the early 20th century. U.S. soldiers eradicated Filipinx villages that included Indigenous tribes and populations. (Photo courtesy of Flickr/George Lane)

But, in fact, it was brutal. And it was genocidal.

If you look at the archival records that survived, we see it was hand-to-hand eradication of people throughout the Philippine archipelago.

This is not to say that there wasn’t militant resistance against the U.S. during this time, but given U.S. military might, and its deeply white supremacist colonial approach to the conquest, they exterminated entire villages, including elderly people, children and everybody in between.

These were war crimes, and U.S. military and state officials from Congress to the White House were unapologetic and proud that they did these things.

So, the origin of the neocolonial relationship between these two countries was a genocidal conquest. And that’s the piece that we have yet to come to terms with.

That was over 100 years ago: What does this history of colonialism, conquest and genocide in the Philippines have to do with how the world is viewed today?

I think we need to understand that the violence of conquest never goes away.

Hundreds of thousands of people, possibly millions — but we’ll never know — were killed in the Philippines. And the United States has never acknowledged this.

I put this history of U.S. genocide in the Philippines out there for whomever will receive it. It may (modify) whatever romantic narratives they have in their heads about the history of the U.S. that hinge on the fraudulent promise that the nation encompasses some kind of democratic ideal.

To the contrary, the dominant U.S. national narratives do the violence. Those narratives are the violence because they normalize the transgenerational damage of U.S. conquest and empire.

So, these narratives need to be challenged and exploded.

As we’ve learned from Indigenous and Aboriginal communities of people, as well as African-descended peoples all over the planet, the time of colonial conquest and genocide, the time of transatlantic slave trade and plantation slavery — that time has never gone away.

In colonialism and conquest, “we still see the remnants of this in state violence, in American police departments that can never exist without primarily targeting Black people, and other people of color, for ad hoc and systemic violence,” said Rodríguez. (AP photo by Max Becherer)

What is the influence of colonialism and conquest in our everyday lives?

Conquest is inseparable from who you are and what you want to become. It constitutes what you do and the way you understand the world around you.

For example, a lot of self-identified Filipinx Americans can only speak English. They don’t speak Tagalog, Ilocano, or any of the other Philippine dialects. So, they don’t know the languages that inform so much of their own Filipinx identity. The language that their ancestors used to tell stories and pass down histories.

They are detached from this history.

The trick of assimilation is that even if you’ve assimilated, you’re not just complicit in it, you become part of this genocidal, imperial project.”

– Dylan Rodríguez

That seems like such a simple point, but it’s a “simple point” constituted by a long legacy of occupation, violence and colonial domination.

Colonialism and conquest also influence how we view things like justice and the way we relate to authority, especially state authority. If we look at President Duterte in the Philippines and his war on drugs, we see state violence that is exterminating people as an exercise of pure police power. And much of the voting populace is aiding and abetting him.

Where does this complicit support for fascistic state violence come from? It’s not an Indigenous way of thinking. That’s not even a Catholic way of thinking.

It’s colonial.

After the Philippine-American War, many Filipinx women were schooled in the art of western nursing, a profession that millions of Filipinx people continue to serve in today. Here, a senior class receives instruction in operating room techniques at the Philippine General Hospital in 1915. (Photo from the U.S. National Archives, College Park, MD.)

We see this impact in everything we do. We need to decolonize and liberate our physiological and psychological ways of being to stop the long violence of conquest and genocidal occupation.

Is it then important for academics to decolonize research? If so, what does that mean?

I think people who are engaged in the most meaningful forms of decolonizing research don’t necessarily think about what they’re doing as “decolonizing research.” They’re doing research, yes, but they’re also, more centrally, part of and active in movements for actual decolonization.

There is no afterlife to conquest, genocide or slavery… They can’t simply be compartmentalized away.”

– Dylan Rodríguez

So, “decolonization” is the priority, and the “research” flows from that priority. Research emerges through direct interaction with the decolonization struggles, practices and communities that people are a part of. That, to me, is the most meaningful interpretation of your question.

Otherwise, decolonizing research devolves into a (made-up) formulation that allows academics to remain comfortable within the traditional research enterprise, without having direct responsibility and ties to decolonizing movements, communities, organizations and struggles.

How can those communities come together and be empowered by this history and research?

Let me respond to your question in a way that also addresses the current historical moment. It seems to be increasingly well understood that Black people are primary targets of everyday police and state violence, in an ad hoc as well as a systemic way, in and beyond the U.S.

Being Black in this world, on this planet, but especially in this hemisphere, is to exist as a primary target of sudden, unexpected state violence in various forms, regardless of class position.

If we can come to this agreement, then the question becomes: How do people who want liberation from such violence engage in the fight?

There are lots of Black and non-Black people alike who want to be engaged in this fight. However, the ways in which they engage may reinvest in the dangerous hope that the state will somehow fix itself.

Pro-police protesters throughout the U.S. have expressed support for the Blue Lives Matter movement in defense of police killings. “To believe the police can be ‘reformed’ away from a foundationally homicidal, genocidal relationship to criminalized Black people, and other targeted populations, is another kind of colonial thinking,” said Rodríguez (Photo by David Geitgey Sierralupe via Wikipedia)

For example, many believe that certain public policy changes will somehow stop or slow anti-Black police violence, including police killings. Others allow themselves to be convinced that police departments can magically train their officers to stop criminalizing and violating Black people as a matter of daily routine.

Yet, there is massive empirical, anecdotal and ethnographic evidence that shows how modern police institutions — especially in the U.S. — are fundamentally unfixable in these ways.

The police simply cannot exist apart from anti-Black state violence.

To believe the police can be “reformed” away from a foundationally homicidal, genocidal relationship to criminalized Black people, and other targeted populations, is another kind of colonial thinking. This form of colonial thought is distinct from, but still deeply related to, the colonial legacies of the U.S. and the Philippines.

In this case, I’m saying that “reforming the police” doesn’t work. The police cannot be “decolonized” and still exist. The institution has to be abolished.

“I want to be engaged in a fight with people and with communities who care about me, who are responsible to each other and who treat each other with a little bit of grace,” Rodríguez said. (Photo courtesy of Flickr/Kenny Chang)

All this to say, I want to fight alongside people and communities who care about each other, are responsible to each other, and treat each other with a little bit of grace.

What I mean by a fight, in the broader sense, is a form of community based on a shared desire for liberation, beauty, and self-determination. As well as a shared understanding that these things must be created through struggle.

The fight can happen in the context of religious communities, co-ops, neighborhoods, blocks or whatever. The important thing is that in being together, fighting alongside each other, there is a possibility to build dynamic relationships that draw connections between different histories, identities and positionalities.

In these spaces, we can make each other better and be righteously critical of the work we do, while also being graceful with each other. These are the spaces where meaningful decolonizing changes can happen, because, otherwise, we would just be performing another academic exercise.