Berkeley Voices: How Roe v. Wade radically changed American culture

When abortion was legalized in the U.S. in 1973, “it changed everything,” says Kristin Luker, a professor emerita of law and of sociology at UC Berkeley. “It was so revolutionary — I argue it was on a par with the American Revolution.”

June 29, 2022

Follow Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast about the people and research that makes UC Berkeley the world-changing place that it is. Review us on Apple Podcasts.

See all Berkeley Voices episodes.

When Roe v. Wade was handed down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1973, which protected the right to an abortion, “it changed everything,” says Kristin Luker, a professor emerita of law and of sociology at UC Berkeley. “It was so revolutionary — I argue it was on a par with the American Revolution or the French Revolution.”

Last Friday, the Supreme Court voted to overturn Roe, giving states broad power to curtail or end abortion. As of today, abortion is now banned in at least seven states, and about half of states across the country are expected to ban or severely restrict the procedure in the coming days.

In this Berkeley Voices episode, Luker talks about why doctors began writing anti-abortion laws in the 19th century, the experiences women had ending unwanted pregnancies in the decades before Roe v. Wade and how she doesn’t see us returning to the normative sexuality and reproduction of the 1950s.

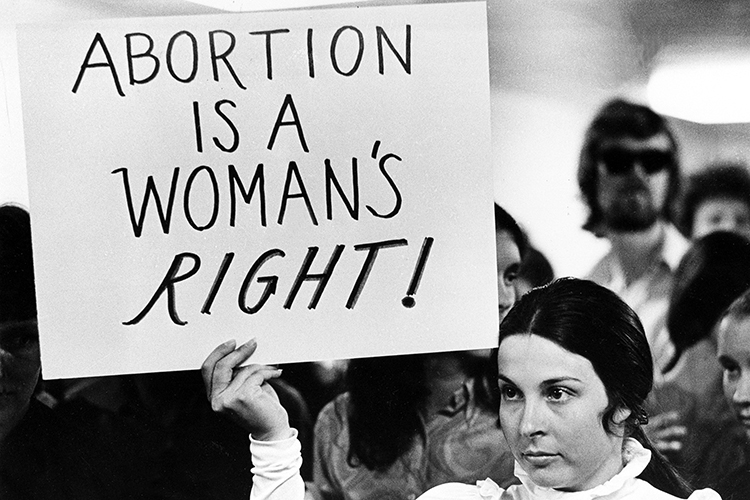

A person holds a sign demanding a woman’s right to abortion at a demonstration to protest the closing of an abortion clinic in Madison, Wisconsin, in 1971. The clinic was closed after authorities said more than 900 abortions had been performed at the facility in violation of the state’s abortion laws. Two years later, Roe v. Wade legalized abortion nationwide. (AP photo)

Read a transcript of Berkeley Voices episode 100: How Roe v. Wade radically changed American culture:

Kristin Luker: It was, to my understanding, that pretty much every sorority on the Cal campus had somebody who knew somebody who could get you in touch with an illegal abortionist.

[Music: “Discovery Harbor” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Anne Brice: Kristin Luker is a professor emerita of law and of sociology at UC Berkeley, where she taught for more than three decades. Luker is co-founder and faculty director emerita of Berkeley Law’s Center on Reproductive Rights and Justice. She has written five books, including Taking Chances: Abortion and the Decision not to Contracept in 1975 and Abortion and the Politics of Motherhood in 1985.

In her research, Luker has interviewed hundreds of women about their experiences with abortion before and after 1973, when the U.S. Supreme Court handed down Roe v. Wade, a landmark decision that protected a woman’s right to an abortion.

Here, she’s talking about the options Berkeley students had if they wanted to end a pregnancy in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Kristin Luker is professor emerita of law and of sociology at UC Berkeley, where she taught for more than three decades. (Berkeley Law photo)

Kristin Luker: The rumor was that there was a kindly doctor on Telegraph Avenue who would — although he, himself, would not do abortions — would refer you to reasonably competent practitioners in Tijuana.

If you didn’t do that, then you could try to abort yourself and some of the people I interviewed did. You could go to what a woman I interviewed called a “granny midwife.” That is someone who has had a lot of experience with births and, I presume, abortion, but no professional training.

Anne Brice: Today, I’m joined by a colleague of mine, Edward Lempinen, a writer for Berkeley News at UC Berkeley. He recently spoke with Luker about what it was like for a woman to end an unwanted pregnancy before Roe v. Wade and how the right to an abortion dramatically changed American culture.

Luker also discussed the recent Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe, and how she doesn’t expect to see women going back to the normative sexuality and reproduction of the 1950s.

This is Berkeley Voices. I’m Anne Brice.

A quick note for our listeners: Throughout this episode, we use the term “women” for people with the capacity for pregnancy, but we do recognize and appreciate that transgender and non-binary people also need access to abortion and other reproductive care.

[Music fades out]

Welcome to Berkeley Voices, Ed.

Edward Lempinen: Thanks for having me, Anne. It’s good to be here.

Anne Brice: Ed, first, can you give us a rundown of the decision that the Supreme Court handed down on Friday?

Edward Lempinen: Yeah. The Supreme Court, dominated by six conservatives, overturned Roe v. Wade, ending the constitutionally protected right to an abortion after nearly half a century.

Their vote was focused specifically on a Mississippi law that prohibited abortion after 15 weeks, but the justices went much further, giving the states broad power to curtail or end abortion.

At least nine states moved quickly to impose bans on abortion and about half the states in the country — conservative states in the South and Midwest and West — are expected to ban or severely restrict abortion access in the coming days. Some states don’t even have exceptions for rape or incest.

And the women and families who will suffer the most are the most vulnerable in our country: poor people, young people, people with disabilities, undocumented people, people of color.

Anne Brice: In your conversation with Luker, she talked about how far people would go to end unwanted pregnancies in the decades before abortion was legalized.

Edward Lempinen: Yeah, she has heard a lot of really harrowing stories about the danger and shame and terror that women experienced.

[Music: “Careless Morning” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Kristin Luker: A friend of mine flew down to San Diego and went over the border and was met by somebody in a car with dark windows and was told to lie down on the floor of a car and was driven to a place — this is in the middle of the night, by the way — and was given the abortion, no anesthesia. It seemed like there was probably sterile technique, although she wasn’t paying that much attention.

And after it was over, they dumped her on the street corner in Tijuana. So, that’s what life was like before Roe v. Wade. It was the bad old days.

[Legal] contraception and abortion changed American life. It was so revolutionary, I argue it was on a par with the American Revolution or the French Revolution.

Edward Lempinen: Do you have any recollection of what happened to the woman who was dumped on the street corner in Tijuana after that?

Kristin Luker: Well, she came back, she finished college, she got married, she had a normal life. And I’ve never asked her this — I have been in touch with her, by the way. I’ve never asked her this, but many of the people that I interviewed never told anyone about their illegal abortion.

Anne Brice: For a woman at the time, giving birth to a baby when she was unmarried was considered shameful and morally corrupt. These women were discriminated against in all sorts of ways.

Kristin Luker: I ended up interviewing people who went away “to visit an aunt in the Midwest,” which was a code for being sent away from home and having your baby with no one noticing. And even as late as the mid-1960s, women were told that they should go back, they should resume their life. They should never tell anyone about having had a child or an abortion, as the case may be. And I know many women who didn’t talk about it until after Roe v. Wade.

[Music fades out]

Anne Brice: Luker has another friend who was unmarried and gave birth. She was attending a religious school and decided to give her baby up for adoption.

Kristin Luker: And while all the other mothers on the maternity ward were allowed to look at their babies, she was not. She was not allowed to hold her baby. She begged to just have a look at her baby. They made her walk to the nursery after a C-section, when all the other women, most of whom had not had C-sections, were taken in a wheelchair. So, I can’t convey to you the stigma and the terror and the shame that faced women who had pregnancies they did not want.

Edward Lempinen: When you talk to women who went through that kind of difficult situation, and you talk to them years after the fact, did you have a sense that it changed them, or that the stigma or the sense of loss lingered with them?

Kristin Luker: It changed them, but not in the way you would expect. Now, I know a select group, because in my interviews, I interviewed people who were activists. That is, the people who were actively seeking to change abortion laws or actively seeking to oppose the changing of abortion laws.

And the women who had illegal abortions or had children out of wedlock, had what my generation would call a “click” experience. The minute they heard there was a movement to liberalize abortion laws, they said, “Count me in.” And they came out of the closet, and they started telling people. It was almost a religious experience.

[Music: “Lakeside Path” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Anne Brice: In 1964, three activists in the Bay Area founded the Association to Repeal Abortion Laws, or ARAL. The three women were such a powerful force that they earned the nickname the Army of Three. At the time, says Luker, the medical and legal professions were talking about abortion reform. But the Army of Three was talking about a full repeal.

Kristin Luker: They were amazing, amazing women. And I was lucky enough to be able to interview some of them. They were passionate. They were dedicated. They got themselves arrested.

And these three women set up an illegal referral system to abortionists in Tijuana. And they would go down, and they told me they did a white-glove inspection. And if the place did not pass a white-glove inspection, that person did not get any referrals.

They also made all women write a letter to their legislator before they would give them the referral, and they urged women to come back and post what you and I these days would call a Yelp review: How was it? How were you treated? And that was the beginning of a new world about abortion.

So, it was a very early awareness of your rights as a woman and your right to control your own body. Those were extremely radical ideas. And that was the beginning of a new world about abortion.

Anne Brice: The Army of Three’s Association to Repeal Abortion Laws would eventually become NARAL Pro-Choice America, a nonprofit today whose 2.5 million members fight for reproductive freedom for everybody.

[Music fades out]

Edward Lempinen: In listening to your descriptions now, and in reading your book, Abortion and the Politics of Motherhood, I’m struck by the fact that, at least me, personally, I think of abortion as a relatively modern phenomenon. I think of it in the ‘60s. I think of it post-Roe v. Wade. But, in the book, as you describe it, it has been a debate and a conflict in American culture since the 19th century, at least. And I wonder how the debate has changed?

Kristin Luker: Actually, it’s surprising because it has not changed that much. To me, that’s the surprising part.

We have data back to the colonial periods of people trying to end unwanted pregnancies with herbs and horseback riding and throwing themselves down stairs. But one of the things I point out in that book is that until the 1920s, there were no accurate pregnancy tests, so there was no reliable way to figure out if you were pregnant.

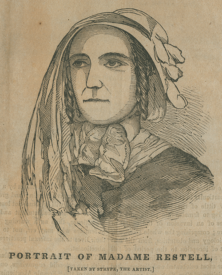

British-born Ann Lohman, whose alias was Madame Restell, performed abortions and distributed contraception in New York City in the mid-19th century. (Illustration by Frederick C. Strype)

Anne Brice: Luker says abortion in the 19th century was actually quite common. There were ads in newspapers for “female pills” that brought on menstrual periods. Abortifacients, or substances that would cause miscarriages, were openly advertised in storefronts.

Although there were few female physicians, some women called themselves “female doctors” and provided abortions. And midwives specialized in women’s health, contraception and abortion.

Kristin Luker: It was considered something that women did. It was part of the women’s world. In San Francisco and Los Angeles, there were clinics for ladies who said they would take care of “menstrual obstruction from any cause.” Now, for a healthy, sexually active woman, the main cause of menstrual obstructions was probably pregnancy.

Anne Brice: It was a common perception that if a woman hadn’t felt the fetus move, or “quicken,” then abortion wasn’t particularly controversial, says Luker. After all, in a time before sonograms, quickening, which usually happens in the second trimester, was the only way to know for sure that a woman was pregnant. An abortion was generally considered immoral or, in some cases, illegal after quickening.

[Music: “Checkered Blue” by Blue Dot Sessions]

In the mid-19th century, though, things were changing.

Luker says there was a very special group of doctors — highly educated, white, upper-middle class doctors called “regulars” — who, after realizing that married women were having abortions, became enraged and began to agitate and pass abortion laws beginning in the late 1850s.

Kristin Luker: And I make the argument that these doctors are engaged in what a sociologist would call a professionalization project, meaning they couldn’t actually cure people. They didn’t really have much to offer people.

But what they could do was stake a moral claim. And the moral claim they made was it’s a baby from conception onwards, which is, as you know, the language that’s being used now.

Anne Brice: Between 1860 and 1890, doctors wrote abortion laws through their state medical associations. By the late 1800s, all states had laws to restrict abortion, with exceptions in some states if a doctor said the abortion was needed to save the life or the health of the patient, or for therapeutic reasons.

Kristin Luker: Which means that an abortion is completely legal if a doctor thinks it’s necessary, but it’s completely illegal if a woman thinks it’s necessary. So, I point out this is a profound contradiction, which is, either it’s a baby from conception onwards or it’s not. But you can’t have it both ways, which is what American doctors did.

Anne Brice: As abortion became criminalized, the stigma surrounding it grew.

[Music fades out]

Edward Lempinen: Thinking of life before Roe v. Wade and after Roe v. Wade, how did the availability of legal abortion change women’s lives? And, more broadly, how did it change American culture?

Kristin Luker: I think it changed everything. The book I’m finishing argues that contraception and abortion changed American life on a par — it was so revolutionary, I argue it was on a par with the American Revolution or the French Revolution.

And the reason I say that is because it changed how people thought about it. It changed how people talked about it. It changed how people experienced it. And, most importantly — and this is, by and large, being left out of the current debate — it permitted women, that is, women like me, to invest human capital in themselves, confident that they would not have to interrupt their education or their professional career by having a child.

And I tell this story: When I was in graduate school at Yale, there was a very plum fellowship that I was eligible for and I was told I couldn’t have it because I was a woman and I might get married and have children. The man who was given the plum fellowship funnily enough got married and had children long before I did. But nobody thought that was a problem for men.

The political philosopher, Susan Moller Okin, says that in political philosophy, women have always been mothers or potential mothers. They have never been citizens. I believe that with Roe v. Wade and with contraception, they became citizens for the first time ever. That’s what at stake right now.

Edward Lempinen: Wow. In the introduction to your book in 1985 you wrote, “The abortion debate is likely to remain bitter and divisive for years to come.” And looking at that now, it was amazingly prescient. But I wonder, why do you think this debate has remained, across these years, so prominent and so intense?

Kristin Luker: I believe abortion brings up questions of what sexuality is supposed to be for. Can it only be used for procreation, or can it be used for something else? It brings up issues of marriage that, as you probably know, people, the demographers, call it “the retreat from marriage.” And it brings up questions of gender.

And I think the most subtle thing, and this has become much clearer on the horizon, is it brings up the issue of social worthiness. So, people who who oppose abortion imagine that women are casually going out and ending their pregnancies because they have better things to do.

We have data from UC San Francisco — The Turnaway Project — that [find], you know why women get abortions? They get abortions because they cannot afford to have another child, and they get abortions because of their commitments to other people — to the children they have, to elderly people, to their families. So, far from a selfish decision, it’s exactly the opposite. And I think for most women, it’s a very carefully thought-through and least-worst solution.

[Music: “Kallaloe” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Abortion rights rally in New York City on June 24 after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. (Photo by Elvert Barnes via Flickr)

I profoundly trust women to know what’s best for themselves and for their families.

I’m a person who’s been converted to the notion of reproductive justice rather than reproductive rights. Reproductive justice insists that reproduction includes the right to have a child, the right to raise a child in dignity and some measure of comfort, and the right to build a family in whatever way you see fit. I’ve always been a reproductive justice person. I just didn’t know it.

Anne Brice: Luker says the recent Supreme Court ruling has shown us that the abortion debate and conflict isn’t going away any time soon.

Kristin Luker: Two things that I find interesting. One is, I think this is, in part, a symbolic battle. This is a way of validating the traditional heterosexual married couple as the only form of legitimate sexuality. And it’s not surprising that some of these same people are going after LGBTQ rights because, in fact, those rights have come into being by much the same logic as abortion came into being.

On the symbolic plane, the second thing is, and I think they’ve been remarkably successful at this, I think the pro-life people want to stigmatize abortion. They want women to go back to the generation I grew up in, where women were terrified and ashamed and silent. And I think that’s, in large part, what this debate is about.

People not that much younger than I am grew up with abortion being legal, and they cannot imagine a world in which it’s illegal. How that’s going to play out is anybody’s guess. Do I think women are going to go back to the kind of normative sexuality and reproduction we saw in 1950? I don’t think so. And, well, I guess it’ll be interesting to see.

Anne Brice: Kristin Luker is a professor emerita of law and of sociology at UC Berkeley, where she taught for more than 30 years. She is co-founder and faculty director emerita of Berkeley Law’s Center on Reproductive Rights and Justice. You can learn more about the center at law.berkeley.edu.

This is Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast from UC Berkeley’s Office of Communications and Public Affairs. I’m Anne Brice.

You can follow Berkeley Voices on Spotify or wherever you listen. If you like what we do, please follow us and leave us a rating and a review. You can find all of our podcast episodes with transcripts and photos on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

Listen to other Berkeley Voices episodes: