Student des marie jackson: ‘Find purpose by staying centered in your passions’

How a Berkeley student is reimagining the research of California’s rural areas

June 30, 2022

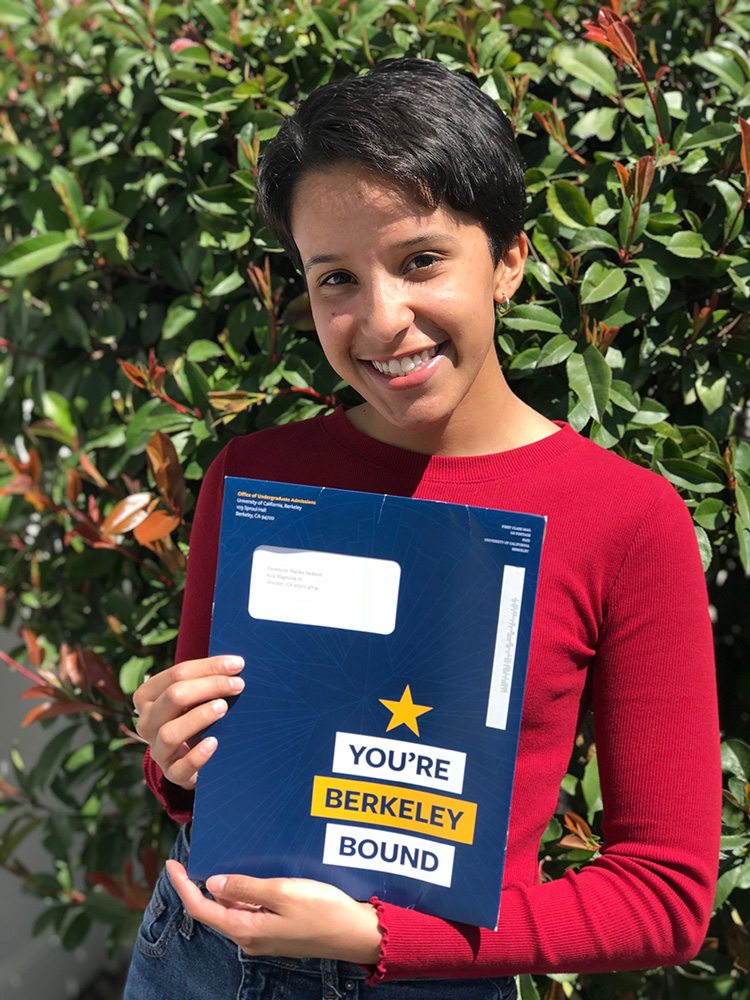

Berkeley student des marie jackson is reimagining the research about California’s rural areas informed by their life growing up in Atwater, Calif. (Photo courtesy of des marie jackson)

This I’m A Berkeleyan feature was written as a first-person narrative from an interview with des marie jackson. Have someone you think we should write about? Contact [email protected].

I’m an Afro-Latinx, non-binary, queer, trans poet and activist. I want to be a scholar that troubles academia.

I want to reveal social inequities and conduct research that lifts the veil off the nebulous of white supremacy and post-colonial oppression. I want people to care about Central California’s rural areas and the farmers that feed us, because that’s where I’m from.

I want to write poetry that is therapeutic and disruptive. Writing that empowers my communities and the people around me. I want my family to be proud of who I am. I want my brother to have the resources he needs as a disabled person.

Poetry has been an outlet for jackson to express new emotions and thoughts around the intersectionalities of their identity. (Photo courtesy of des marie jackson)

I want to give back to my communities with integrity and without compromise. I want to share my journey in the hopes that it will help others who have had similar experiences.

I want to change the world around me.

When I was a child, my parents were unfit and didn’t have the resources to take care of my brother and I. So, at the age of 2, I began living with my grandparents.

My grandfather served in the Air Force and Army for 27 years and traveled around the world, but decided that Atwater, California, was where he wanted to retire and settle down with my grandmother.

Atwater is a really small rural town in the Central Valley. I like to call it the heart of the state because the area produces so much agriculture, and it is geographically located in the center.

Growing up in a middle-class suburb of Atwater, there wasn’t much to do, but my family always found a way to keep me busy. My brother and I spent most of our time playing and dreaming in our backyard. We loved to build things with Legos together to make little worlds and spaceships that came from our imaginations.

Childhood photo of jackson, right, and their older brother in Atwater, Calif. (Photo courtesy of des marie jackson)

My family tells me that as kids we were so close that I was the only one who could translate what he was trying to say — on account of his speech impediment. We have always had each other, no matter what.

My grandparents loved us and gave us everything we needed, but we grew up in a very strict Mexican Catholic household, so I often felt pressure to be perfect. The community, which was predominately white and Mexican, had a similar culture. I found that my worldview was very different from those around me, and at the same time my experiences and mixed identities meant it was not safe to be QT.

I had learn how to be loud.

As a child, having to sift through and understand all of these different identities I had was hard. Atwater also had a lot of conservative, xenophobic and white supremacist groups like the Proud Boys. This racial tension was everywhere, and I felt it even in grocery stores and restaurants I visited with my family. In school, I was always one of the smartest students, but was told that I was too talkative and to “watch my attitude.”

Things you thought stopped happening in the 1950s were still alive and well in this little rural town. And these microaggressions really made me curious about why my community was the way it was.

Being in band gave jackson a community to be their genuine self. Here they pose with a fellow high school marching band member in Atwater. (Photo courtesy of des marie jackson)

In high school, I found an accepting community by playing clarinet for the band. It’s funny, they say if you want to find the QTs at any school, go to the band or theater departments. It’s a stereotype, but it was true for me. I made lifelong friends — my real besties — that I felt safe being around.

We created spaces for each other to be ourselves.

After graduating from Atwater High School as valedictorian in 2018, I knew I wanted to leave Atwater and go to college somewhere else. I felt like the education system in the area was underfunded, conservative and not as open to teaching critical curriculums as others might be. While the educators at local community colleges were becoming more critical, I wanted the chance to explore new places while I had the time and money.

Jackson’s grandparents always instilled the importance of education in them as a young kid. (Photo courtesy of des marie jackson)

As someone who is mixed-race, I still had a lot of questions about race and how it positions certain people over others. And the discourse I needed to understand myself and the world around me was not being provided.

Why, as a lighter-skinned person of color, was I treated differently and seen as more Latine than my brother, who is visibly Black? Why was it easier for me to access my Mexican identity because of that? How did I benefit from this in a predominately white, anti-Black, rural town?

I chose to go to Berkeley because I knew these critical questions were being discussed. And I knew the Bay Area would be a safe haven for me as a poet, scholar and activist. When I stepped on campus, I fell in love with it: My world, my bubble, for the first time existed beyond Atwater.

It was a surreal experience.

As a scholar, my academic interests at Berkeley flourished. I majored in comparative literature, French and Latin, with a double minor in African American studies and education. My mentors and campus leaders — like Dr. Kerby Lynch and Dr. Tianna Paschel — have helped expand my perspective through Black scholarship and intellectualism that has been fulfilling and regenerative for me.

For jackson, Berkeley represented a safe haven for the queer community and an opportunity to participate in critical discourses important to their identity. (Photo courtesy of des marie jackson)

Berkeley’s Black community really allowed me to get in touch with my Black identity. As an African American Initiative scholarship recipient, I have also been given the privilege and time to stay deeply involved in the queer and trans communities of color on campus.

I am an active participant in the Gender Equity Resource Center and have served as an intern for the Black Student Union. As a former resident assistant, I have worked to create welcoming spaces for Black students in campus dormitories.

I also worked as the Black Themtorship Lead for Central Valley Scholars, a program that provides resources for Black, undocumented, first-generation college students in need of support. This year, I’m on the planning committee for October’s UC-wide BlaQout conference, which is for Black, queer and trans students across the state of California to gather and build community.

I plan to graduate in spring 2023, and my honors thesis is about language discourse and colonialism. This topic has been inspired by all the critical theory courses I have been able to take at Berkeley that have allowed me to make tangible connections between the lived realities I take with me from my hometown and the patterns of oppression that persist in other rural areas in California.

How does historical land ownership allow for white supremacists to easily insert themselves into these rural local governments? Why are these people the ones distributing resources and exploiting labor? How do they get to define the lived experiences of oppressed people in Atwater? How do all of those things happen?

Doing this work and research at Berkeley has been really dope. It has allowed me to connect my academia with my deep connections to the Central Valley and my hometown. It’s a real full circle moment for me.

When jackson first came to Berkeley, they said the beauty of campus was a surreal experience. (Photo courtesy of des marie jackson)

Thanks to my Berkeley mentors, and the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship, this summer I am attending an intensive research training program at the University of Chicago for future professors. It begins to give you all the resources, critical connections, and relationships you need to be a great scholar.

I am building bonds with like-minded students who also want to turn this ivory tower on its head.

It gives me hope, but with so much opposition to progress, this work is not easy. I find strength in my family, especially my brother, who always reminds me to be kind and patient.

To forgive.

While I am on this scholarly path, I try to stay open to opportunities that come my way. I see my purpose in life sometimes like a Venn diagram, and I’m trying to find the center where my passions, my skills, and how I can be useful or give back, all meet.

But I find purpose by staying centered in those passions and the people and communities I care about. And coming from a place of privileged academia, I deeply feel I have a responsibility to give back with integrity and without compromise. Given my lived experiences, and the communities I come from, it’s also about a means of survival for me.

I’m from a community where people are still living on water wells, through droughts and with a lack of the basic needs to live. My family, my loved ones, and countless more live in this community, so this is not a game for me, or for us.

I want my research and work to build sustainable, survivable and thriving futures for them and others. And as a scholar at Berkeley, that’s what I’ve been able to advocate for, and I now have a real stake in making that happen.

So, this journey has really come full circle for me. I’ve found my center.