How community spaces can empower students to mobilize, explore their identity

UC Berkeley professor will host a panel discussion with Crip Camp creators as part of the Disability Cultural Community Center grand opening celebration.

October 21, 2022

UC Berkeley’s new Disability Cultural Community (DCC) center celebrated its grand opening on Oct. 25. in the space’s main multi-purpose room. As part of the festivities, Berkeley professor Karen Nakamura, right, moderated a panel discussion with the director, and cast member Judy Heumann, of the documentary Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution. (Photo courtesy of Ann Wai-Yee Kwong)UC Berkeley photo by Sofia Liascheva)

Growing up the child of cultural anthropologists, Karen Nakamura traveled around the world living in places like Indonesia, Australia, New Zealand and Japan. And while being exposed to different cultures and communities at a young age helped her to conceptualize the world around her, Nakamura said she didn’t have a real sense of her own identity.

Karen Nakamura

“It was hard for me to identify as just one thing,” said Nakamura. “But as I began to explore different community spaces, I came to realize that I could exist across the various parts of myself. That my identity didn’t have to be so monolithic.”

Now, as a UC Berkeley cultural anthropology professor, Nakamura, who is part of the Asian American, queer, genderqueer and disabled communities on campus, has focused much of her Berkeley Critical Disability Lab research on thinking through formation of identity and how people can create movements and spaces for identities to flourish.

The lab’s unofficial motto is “making better crips since 2018.”

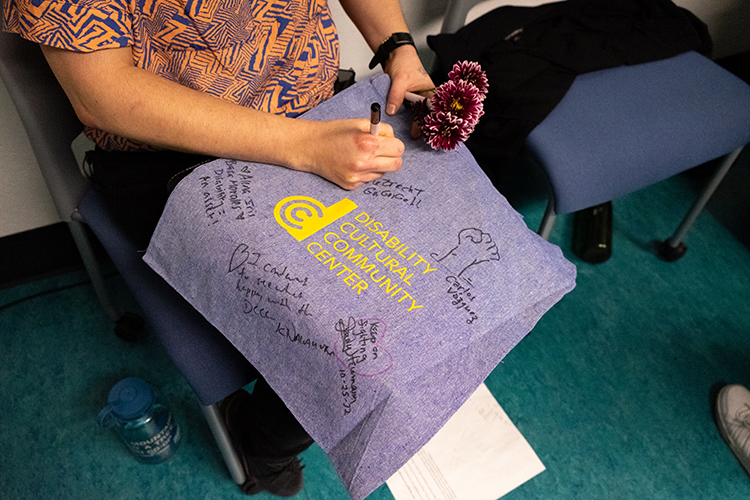

On Oct. 25, Nakamura moderated a Berkeley panel with Jim LeBrecht and Judith Heumann — the director and cast members of the documentary Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution — and discussed disability movements from the past, present and future. The event was part of the grand opening celebration of Berkeley’s Disability Cultural Community (DCC) center, located in the Hearst Field Annex (Suite D-25).

The DCC is one of the first college campus centers in the country to be dedicated solely to the disabled community, said DCC Director Ann Wai-Yee Kwong. With over 2,100 square feet of space, the center will provide student programming, resources, and counseling. It will also host community events and conferences for Berkeley’s disabled students.

Hearst Field Annex’s D-wing. The surrounding area near the center “is flat, accessible and it has great access to restroom areas, which is very important. … and it is very close to Sproul Plaza,” said Nakamura. (UC Berkeley photo)

Students like Alena Morales advocated for a disability cultural center. (Photo courtesy of Alena Morales)

Nakamura said the center will, more importantly, serve as a space to build community for disabled students away from medical-related services. A place where students can explore their intersectional identities together and mobilize.

“It was really the students who, for years, advocated and protested for this space, often in front of California Hall, and really forcefully stated that they needed a center,” Nakamura said. “They were part of their own movement that has now created the DCC for generations of students to come.”

Berkeley News spoke with Nakamura recently about how new community spaces can help build political power and why it is important for students to understand the history of the disability movement to move forward.

Berkeley News: Do you think the public-at-large sees folks in the disabled community as a monolith?

Karen Nakamura: Yes. But I think a lot of the new media and films, like Crip Camp, are doing a lot to help dispel what a disabled person looks like.

Recently, there has been a lot of discussion at Cal about invisible disabilities, one of the largest areas of growth in DSP. The number of students who are using wheelchairs, or who are blind, has remained relatively the same over the years. The largest growth has been in people with learning and psychological disabilities.

And in some ways, those disabilities are more of a challenge for the university and how it functions. We know how to create ramps, automatic doors and visible fire alarms, but when people are saying they have chronic fatigue and have issues with their normative time of completing requirements to graduate, that’s a fundamental change that the campus has to address.

An updated proctoring center opened recently in University Hall. It provides 100 seats and specialized services for disabled students who need more complex exam accommodations, such as assistive technology, a reduced-distraction environment and extra time. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

I think there is a change, internally on campuses, in how disabled people are seen, especially with the inclusion of invisible disabilities. There are these student movements that are changing the national image of disabilities, and that is impacting what resources are available to students now.

At Berkeley, it was really the students who, for years, advocated for a space like the DCC, often protesting in front of California Hall, and really forcefully stated that they needed a place where they could meet together as disabled students, separate from the DSP. They were part of their own movement that has now created the DCC for generations of students to come.

How valuable is it for students to have this new space on campus?

We call the current generation of students “the ADA Generation,” and they often come to college without a strong sense of their own disability identity. They may have used some services in high school, but don’t identify as disabled.

And so, it’s when they come to Cal that they start to grasp their sense of identity within the community. They’re realizing that their disability identity isn’t shaped by the services they use or by the medical community’s interpretation of their disability. Disability is existing in a world that isn’t designed for you. That’s what forms their identity.

A “misfit” between yourself and the world, to quote Rosemarie Garland-Thompson.

So, being this misfit makes you realize you have to change the spaces you occupy. But also that you exist as this unique being who really needs to be recognized. And I think the push to create the DCC was the realization that students really needed a space to organize and build community that wasn’t DSP or the Tang Center or anything related to a medical context.

A space that they could have where students could interact with each other, build community and explore their identities together. The DCC also gives students a place where they don’t have to feel embarrassed or have to convince someone why they need something specifically for their disability.

Everyone just knows.

How important is the location of the new DCC?

The new Disability Cultural Community Center will be in the Hearst Field Annex on campus. It will be near other centers that serve what Nakamura call’s the campus’s “subjugated communities.” (UC Berkeley photo by Steve McConnell)

Well, I’m excited that it’s three doors down from my Critical Disability Lab. The Hearst Field Annex is flat, accessible, and it has great access to restroom areas, which is very important.

We also have this really great courtyard area to have barbecues or just hang out, and it is very close to Sproul Plaza.

The (DCC) is one of the first college campus centers in the country to be dedicated solely to the disabled community.”

– Ann Wai-Yee Kwong

So, I think there was a real attempt to just make it a place that everyone could locate. It is also near the Fannie Lou Hamer Center, Queer Alliance and Resource Center, and other centers that serve what I call campus’s “subjugated communities.”

I don’t know if that was deliberate or not, but I think it benefits our campus to give students an opportunity to build community in the different spaces that they identify with. And that’s not just for classic disabilities, that also extends to being non-binary, queer and/or being Asian American, Latinx, African American and so on.

I think there is a mutual understanding and connection that is made with other people that feel the same way about a world that so often marginalizes us. That kinship, I think, provides an opportunity for our students to really explore the intersectional identities they encompass and to mobilize.

Do you think having a strong community like that can really help build political coalitions and power?

I think that the goal of the disability movement on campus is to have disabled people feel that they have this home to network and build bridges between other movements. Many of the questions around disability access are things that we share across a broad spectrum.

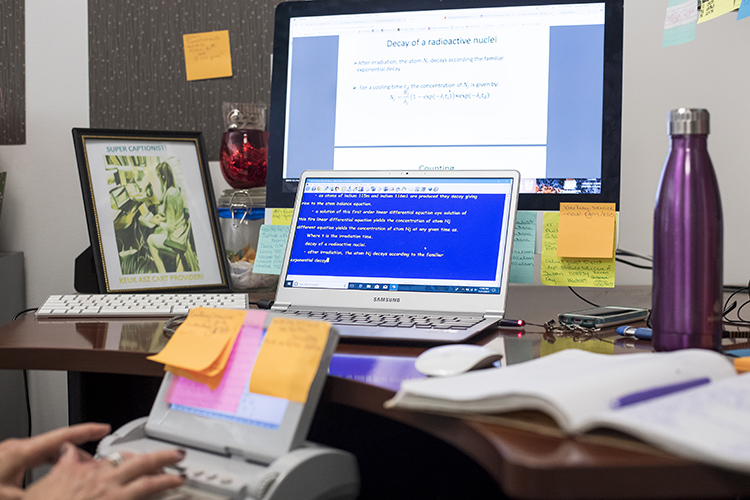

To give an example, in 2017 Cal took down their YouTube channel with 20,000 videos of lectures and talks rather than caption them. The disability community of faculty and students instead tried to advocate for their captioning because captions don’t only help disabled students, they also help students who are having to commute to campus — they can watch the videos on the bus with captions — and it also helps immigrant students who may read English better than they speak it. Or, it could help student-athletes who might need a text transcript to read through quickly because of all the time they have dedicated to their sport.

Staffers at UC Berkeley’s Disabled Students’ Program transcribe a written instructional slide for students who would not be able to easily read the screen during a course lecture. (Photo by Noah Berger)

We can also see how extending normative time to fulfill requirements for disabled students to graduate can also help student-parents, or students caring for elderly family members, who may need that time as well.

So, disability access can help different communities and people on campus. And that is how power and movements grow, when the needs begin to impact more and more people, allies and relationships with other communities are created. And the DCC gives students a space to build those connections.

What do you hope people took from the conversation you had with the creators of Crip Camp?

It’s been over 60 years since those campers met at Camp Jened in the 1960s and birthed the second wave of a disability movement. This span of time can seem almost incomprehensible for students. Has progress been made?

In some ways, I think what I wanted to show is that some of the needs and battles have changed, but we are still a community in need of some basic resources.

Judy Heumann had to really fight for the right to be educated. For students now, that battle has shifted. The focus of the crip camps was on physical disabilities, and so the conversation has shifted also to the struggle around other types of disabilities.

Judy Heumann, left, and Ed Roberts join a 28-day San Francisco protest over housing discrimination in 1977. (Photo courtesy of Bancroft Library)

And so, part of my goal was to show that, in some sense, things have changed significantly. We’ve managed to create a world that has been much more open in a way that is absolutely incredible, but that there’s still remaining tasks, and it’s really sort of incumbent on the students now to take on that mantle, while also respecting history.

In some ways, the disability movement has been really great for people who are white men, upper- or middle-class, and disabled, but hasn’t been as successful for people of color or women who are disabled, or who are poor and disabled. So, we need to really pull that together and start working on issues around intersectional disability.

So, I hope that during this discussion and grand opening we were able to celebrate all the generations of activists that changed the world for us — and who were just totally kick-ass pioneers. But also acknowledge that the struggle has been real, and there are still a ton of things we still hope to accomplish.

And we need continued funding and support to do that.