Student exhibit at Berkeley Hearst Museum aims to decolonize Philippine history

A new DeCal course empowers students to rewrite Berkeley’s colonial past in the Philippines using archival photos and artifacts

October 31, 2022

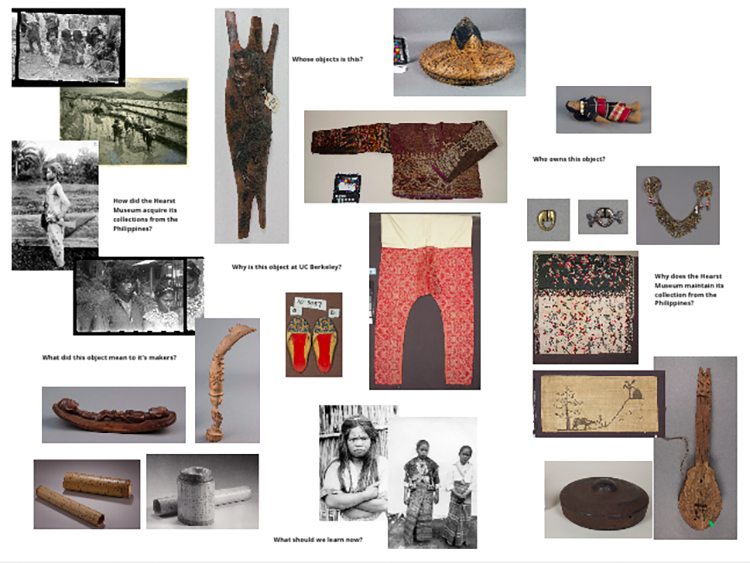

A new UC Berkeley DeCal course empowers students to rewrite Berkeley’s colonial past in the Philippines by curating a student-driven exhibit using photos and images of artifacts from the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. (Photo courtesy of the Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology)

Nina Sanchez says she feels her whole childhood was “whitewashed.”

The daughter of Philippine immigrants, Sanchez grew up in San Francisco’s Pacific Heights neighborhood, going to a private Catholic school with a predominately white student population that would often wrongly assume her ethnicity.

At home, her parents never spoke their native Philippine dialects — Tagalog and Ilocano — opting to make sure she felt more American than Filipinx by speaking English only. She knew nothing of Philippine dances like Tinikling, or Filipinx American labor leaders like Larry Itliong, or iconic poets and writers like Jessica Hagedorn.

Second-year student Nina Sanchez examines a museum exhibit at the Ethnic Studies Library. (UC Berkeley photo by Sofia Liaschaeva)

“I lived in this little bubble and didn’t really know my culture,” said Sanchez, a second-year political science major at UC Berkeley. “I was very in tune with all the white privileged girls, but I struggled fitting in. … I never fully felt comfortable in my own skin.”

But at Berkeley, Sanchez has found a Filipinx American community and begun her own journey of self-discovery through a new DeCal class that has exposed a hidden history — between the Philippines, United States, and of UC Berkeley — she never knew.

Sponsored by the Department of Art History, the two-credit course — UC Berkeley, the Philippines and Filipinx America — began this semester and examines the centuries-long relationship Berkeley has had with the Philippines and the global Philippine diaspora. Students also research the contributions that members of Berkeley’s campus community have had on American and Philippine histories.

More specifically, it examines the early 1900s, during the Philippine-American War, when UC administrators like David Prescott Barrows played leading roles in colonizing the country’s education system and wrote white supremacist textbooks describing “the white, or European, race is, above all others, the great historical race.”

Alex Mabanta is a Berkeley Ph.D. student in jurisprudence and social policy. (UC Berkeley photo by Neil Freese)

Taught by Berkeley Law graduate student Alex Mabanta, the class is also working with campus faculty, librarians and staff on long- and short-term projects to unearth and investigate the Philippines archives and collections across campus.

At the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, DeCal participants are creating a student-curated exhibit that includes images of items chosen from more than 5,000 artifacts from the Philippines, some of which were taken by military personnel during the American colonial period. The items were obtained by the museum — from Barrows and others affiliated at Berkeley — as far back as the museum’s founding in 1901.

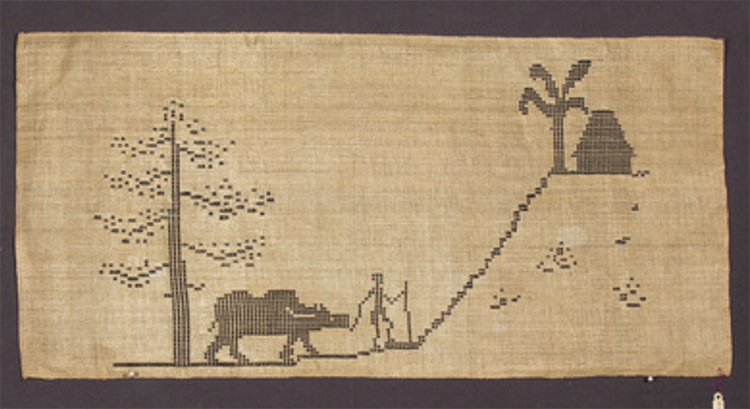

Items in the collection include weapons, musical instruments, clothes, baskets, literary works and over 1,000 photographic prints and negatives. While the majority of the artifacts were collected from living people in the Philippines, some were archaeological and even taken from grave sites in the island archipelago.

The items were initially given to the museum to serve educational purposes, though more archival review is required to document and understand the research they may have been used for, said Berkeley art history professor Lauren Kroiz, who is the course’s faculty sponsor and the museum’s faculty director.

“Through this student exhibit, our class is asking important questions about ethics, imperialism, decolonization and the potential repatriation of these items,” said Mabanta. “What do these objects mean to their original makers? Why are they at UC Berkeley? How were they acquired? Why are they still maintained in the Hearst Museum collection? And should they be returned to the Philippines?”

Countering ‘cultural violence’

“Typical ‘historical’ depictions of Filipinos are represented as primitive and barbaric. Sometimes they are just photos of them disrobed,” said student Cameron Yetta. (Photo courtesy of Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology)

Mabanta designed the DeCal course, in part, as a response to an October 2021 Doe Library exhibit — “Celebrating 50 years of Excellence: South & Southeast Asia Scholarship and Stewardship at Berkeley” — that highlighted Barrows and Alfred Louis Kroeber, another Berkeley professor known for white supremacist views, in a display about the Philippines. The previous year, Barrows Hall and Kroeber Hall, named after Barrows and Kroeber respectively, had been unnamed.

The exhibit was protested by Filipinx and Filipinx American stakeholders on campus after months of campus discussions and a rally on the front steps of the Doe Library. Campus leaders issued a formal apology for the exhibit, “for reinforcing colonial hierarchies of race and nation.”

Berkeley Art History Professor Lauren Kroiz is the course’s faculty sponsor and the Hearst Museum’s faculty director.

The new exhibit at the Hearst Museum, Mabanta said, is an opportunity for students to counter the “cultural violence and historical amnesia intrinsic to representations of Philippine history, and communities, that comes exclusively from the lens of white supremacists and American imperialists.”

Kroiz, whose research delves into early 20th century art and modernism in the U.S. through an ethnic studies framework, has reserved three hallway exhibit cases at the Hearst Museum for Mabanta and his students. The student-driven exhibit will be completed in November and it will continue to be displayed until March 2023.

“Phoebe Hearst thought she was giving us all these objects so that the citizens of California could learn from them. But her idea about what education was then, and what it is now, are different,” said Kroiz. “So, what do we learn from these items now? What stories can we tell with them? How can we make them live on this campus, and for who? … And so, I think the idea that they would live for Filipinx students at Berkeley is really compelling.”

One of the exhibit cases in the hallway of the Hearst Museum that students will use to display their class project. The students have created an outline in each case showing where things will be placed. The exhibit will be completed in mid-November. (Photo courtesy of Cameron Yetta)

Rewriting the narrative

Cameron Yetta, a Filipinx American architecture student, said the exhibit will be a two-fold narrative with juxtaposing — colonial and decolonial — representations of the Philippines. She hopes this representation of the artifacts will show a more authentic view of Filipinx people from that time, and challenge the stereotypes and generalizations the public may already have.

Berkeley architecture student Cameron Yetta has been integral in curating the new Hearst Museum exhibit.

“Typical ‘historical’ depictions of Filipinos are represented as primitive and barbaric. Sometimes they are just photos of them disrobed,” said Yetta. “So, we’re going to show images of them clothed and featuring a lot of their advancements in indigenous culture and technology. … Indigenous wisdom that has been devalued and has gotten lost over time.”

As a Southeast Asian studies major, Jeremy Ramirez said he was “mortified and appalled” when he read DeCal course material that delved into the misrepresentation of Philippine history during the American colonial period.

“This is an opportunity for us to tell our history and present our cultural heritage in a non-derogatory way, outside of the colonialist and imperialist lens,” said Ramirez. “This is a step in the right direction for the university, as all future exhibits should work with the communities they aim to represent.”

Continuing a legacy of activism

Berkeley Filipinx and Filipinx American students played a large role in the transnational organization Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino (KDP). Here a KDP member is dragged out of a building after protesting the U.S. support of Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the 1970s. (Photo courtesy of KDPlegacy.com)

For Mabanta, the course is just one of many ways he has modeled how Berkeley may foster belonging as an institution where Filipinx Americans may thrive. This year, in coordination with the DeCal class, Berkeley, for the first time, held events and celebrations to acknowledge October as Filipinx American History Month.

Mabanta has worked with other libraries on campus to build and invest in community-based exhibits, like the Bancroft Library’s online exhibit that centers on Philippine and Filipinx American histories, and the Ethnic Studies Library’s digital guide that focuses on transnational Filipinx activism in the 1970s.

Mabanta has also connected his students to Filipinx and Filipinx American Berkeley alumni and civil rights leaders from the past. On Oct. 19, Mabanta organized a panel discussion with founding members of the Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino (KDP), a transnational organization from the 1970s — co-founded by Berkeley students and faculty — that fought for Filipinx and Filipinx American civil and political rights in the U.S. and abroad.

The 11 item exhibit at the Ethnic Studies Library highlights the civil rights work of Berkeley students part of the KDP during the 1970s and 80s. (UC Berkeley photo by Sofia Liaschaeva)

The event also celebrated the month-long exhibit at the campus’s Ethnic Studies Library dedicated to the KDP — “An Unfinished Revolution: Transnational Filipinx Activism in the 1970s” — and curated by Berkeley alumnus Michael Castaneda.

“As a library that was born out of the social movement for ethnic studies, it feels important to uplift histories of activism, especially in this global moment,” said librarian Sine Hwang at the Ethnic Studies Library. “Putting this exhibit up for Filipino American History Month was a way to bring more visibility and to support the larger movement for recognition on this campus.”

Former KDP member Maria Abadesco said that intergenerational teaching and sharing of history in the Filipinx American community is paramount to helping Berkeley students continue the legacy of previous activists.

Maria Abadesco, Berkeley Labor Center organizer, speaks at the Oct. 19 event at the Ethnic Studies Library about the importance of passing on the history of civil rights work in the Filipinx American community. (UC Berkeley photo by Sofia Liascheva)

“These bits of history are really important to understanding the foundation of activism in our community,” said Abadesco, who is currently a labor specialist and organizer at the UC Berkeley Labor Center. “… But it’s important for us to not just recognize our history, but also to figure out mechanisms in which we can pass that on.”

And making that history legible for Filipinx and Filipinx American students at Berkeley is something Mabanta said he hopes will continue after he graduates.

“The hope is that new students on campus take up the mantle and continue that rich legacy of civil rights we have here,” he said.

While Mabanta’s DeCal course ends this semester, Sanchez said she will take the lessons and research she has acquired from the class with her, moving forward. She said she hopes the Hearst Museum exhibit really “strikes a chord emotionally” for the greater public.

“These artifacts were stolen by UC Berkeley and held underground, collecting dust. And this should be important to my culture and everyone who goes to Berkeley,” she said. “And learning about the success that my Filipino community has actively had in the past, especially Berkeley students, empowers me to have pride in our history and to be proactive in passing it on to others.”