Exploring the sound of the American Indian occupation of Alcatraz

Ethnomusicology Ph.D. student Everardo Reyes' research looks at how music and radio were used during the 1969 takeover of Alcatraz Island to capture mass attention and amplify the Red Power movement

November 8, 2022

Follow Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast about the people and research that makes UC Berkeley the world-changing place that it is. Review us on Apple Podcasts.

See all Berkeley Voices episodes.

On Nov. 20, 1969, a group of Indigenous Americans who called themselves Indians of All Tribes, many of whom were UC Berkeley students, took boats in the early morning hours to Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. They bypassed a Coast Guard blockade and took control of the island. The 19-month occupation that followed would be regarded as one of the greatest acts of political resistance in American Indian history.

Everardo Reyes is a Ph.D. student in ethnomusicology at Berkeley. After taking several classes with John-Carlos Perea, who last year was a visiting associate professor in Berkeley’s Department of Music, Reyes was inspired to research how radio and music were used during the Alcatraz takeover to capture mass attention and amplify the Red Power movement.

Members of the activist group Indians of All Tribes stand on Alcatraz Island on Nov. 25, 1969, five days after the 19-month occupation began. (AP Photo)

Read a transcript of Berkeley Voices episode 102: Exploring the sound of the American Indian occupation of Alcatraz.

(Music: “Cornicob” by Blue Dot Sessions)

Narration: On Nov. 20, 1969, a group of Indigenous Americans who called themselves Indians of All Tribes took boats in the early morning hours to Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay.

The federal prison on Alcatraz had been closed for six years, and the 89 protesters aimed to occupy the island, stating that the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie required that unused federal land be given back to Native Americans.

This was happening at a time when Native American livelihoods and cultures were acutely threatened by ongoing termination policies in which the U.S. government terminated the status of more than 100 tribes, withdrawing aid and services and seizing millions of acres of Native land.

Many of the protesters were Bay Area college students, including two of the group’s leaders: Richard Oakes, an Akwesasne Mohawk, from San Francisco State University, and LaNada War Jack, a member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, who was attending UC Berkeley.

As the activists neared Alcatraz, they bypassed a Coast Guard blockade, which had been set up after earlier takeover attempts.

The group made it to Alcatraz Island and took it over. The occupation would become one of the greatest acts of political resistance in American Indian history.

I’m Anne Brice, and this is Berkeley Voices.

(Music fades)

Once they were on the island, the occupiers issued a proclamation to President Richard Nixon and the United Nations that said they would purchase the 16 acres of land for $24 in glass beads and red cloth — an equivalent price to what the U.S. government paid for Manhattan 300 years before.

Everardo Reyes is a fourth-year Ph.D. student in ethnomusicology in Berkeley’s Department of Music.

Everardo Reyes: What ends up happening when they first take it over is there’s just so much support from people within the Bay Area. They start getting generators. They get food shipped in, and there’s powwow drumming. This is the stuff in my research that I’m trying to uncover now. They had meetings and budgets. They had huge plans for the island to really just become this amazing cultural center.

Narration: As the takeover gained more attention and support, President Nixon ordered the Coast Guard to play a role of relative non-interference as long as the occupation remained peaceful. At some points, there were more than 400 Native people and their supporters on the island.

Reyes’ research looks at how sound and music were used during the takeover to capture mass attention and amplify the Red Power movement, a civil rights movement formed by Native American youth in the second half of the 20th century. And Reyes explores how the occupation of Alcatraz — along with other acts of political resistance — led to big changes in federal Indian policy.

Everardo Reyes: Richard Oakes talks about, in interviews, that the ability to play Indigenous Native American music on the island was just so fundamental in that first month that they were there.

And he talks about how they were playing music all night long around the drum — that it was bringing together Native American people from across the United States, but also Indigenous people from Mexico and Canada and South America. So, music is just so fundamental in bringing together communities in this intertribal connection.

Everardo Reyes is a fourth-year Ph.D. student in ethnomusicology at UC Berkeley. “For me, as an Indigenous scholar, I’m trying to really think critically on what music is and who defines it and what that means,” he says. “And sometimes my research doesn’t deal with music with a capital M, but I’m thinking of music as law, as art, as land.” (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Narration: Reyes is a musician — he plays several instruments, mostly self-taught — and he’s part of the Designated Emphasis in Indigenous Language Revitalization program at Berkeley. So, this connection among different Indigenous communities that happened on Alcatraz feels especially meaningful to him.

Everardo Reyes: My grandfather was Raramuri, which is an Indigenous community in Chihuahua in the Sierra Madre mountains. I mean, Alcatraz, it reverberates and it influences me when I read pamphlets of them talking about the importance of language and the importance of having a space for students to come and feel comfortable with their Indigenous ways of knowing. Even though that happens in 1970, it resonates with me now, and so I feel like I have that connection.

(Music: “Secret Pocketbook” by Blue Dot Sessions)

Narration: The activists on Alcatraz were reaching and connecting with other Indigenous communities by doing interviews with local and national media, but also by broadcasting regular reports of the occupation over the radio.

Using borrowed and donated radio equipment, the activists set up a broadcasting station in the main cell block. The first live broadcast of a show they called “Radio Free Alcatraz” was on Dec. 22, 1969, on KPFA, a station in the city of Berkeley on the Pacifica Network. John Trudell, a Santee Sioux from Nebraska, was host of the program.

(Music fades)

Everardo Reyes: So, we see the ways that media was used, like radio, to really talk about the issues happening on Alcatraz and it allowed for the Indians of All Tribes to be able to control the narrative and counter false information that was given by the United States government.

(Music: “Now that the Buffalo’s Gone” by Buffy Sainte-Marie)

Narration: Each episode of “Radio Free Alcatraz” began with Cree singer-songwriter Buffy Sainte-Marie singing, “Now that the Buffalo’s Gone.”

Lyrics:

Can you remember the times

That you have held your head high?

And told all your friends of your Indian claim

Proud good lady and proud good man

Your great-great-grandfather from Indian blood sprang

And you feel in your heart for these ones

Oh it’s written in books and in songs

That we’ve been mistreated and wronged

Well over and over I hear those same words

(Music fades)

John Trudell: Good evening, and welcome to Indian Land radio from Alcatraz Island in San Francisco. This is John Trudell, on behalf of the Indians of All Tribes, welcoming you. This evening we’ll be hearing… (Fades out)

Narration: In the broadcasts, Trudell often spoke to activists on the island about why they were involved in the occupation and about their activism for American Indian rights.

Here he is in January 1970 talking to War Jack, who, two years earlier, was the first Native American student to be admitted to Berkeley. And in early 1969, she was a leader of the Third World Liberation Front strikes on campus, which resulted in the first ethnic studies courses to be included in the university’s curricula.

Jan. 19, 1970 episode of “Radio Free Alcatraz” from Pacifica Radio Archives:

John Trudell: LaNada is a student at the University of California at Berkeley, and I understand LaNada had some trouble there last spring because of the Native studies courses. Would you care to tell us about that, LaNada? I heard you were arrested there.

LaNada War Jack: Yes, I was involved in the Third World Strike at Berkeley for Native American studies. I was arrested for felonious assault on an officer, which I understand is the usual charge that they charge some of the strike people with. (Young child makes sounds) My son is just leaving… (She laughs)

Narration: In the broadcasts, Trudell discussed ways the federal government was violating Native American rights — by restricting hunting access, setting unfair prices on tribal lands, removing Native American children from local schools and providing inhumane conditions on reservations — to name just a few.

Here’s an episode in which Trudell interviews Bernel Blindman, a Lakota from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, and a student in social welfare at Berkeley.

Dec. 31, 1969 episode of “Radio Free Alcatraz” from Pacifica Radio Archives:

John Trudell: I’ve never been to Pine Ridge. Now, I’ve been to the Rosebud Reservation, my reservation, Sioux reservation, is in Nebraska, and I know how conditions are there. But, how are the work opportunities at Pine Ridge for Indian people?

Bernel Blindman: There isn’t any work on a reservation.

John Trudell: Alright, here’s one thing I’d like to clear up —I know this used to happen to me: People find out I’m Indian and would tell me how lucky I was because I had the government to take care of me. Somewhere along the line, they believe I used to get these fantastic checks of great amounts of money to just do with as I pleased. This isn’t true, is it?

Bernel Blindman: No. Not on the reservation.

John Trudell: I know at home on our reservation, the older people live on social security and government commodities.

Bernel Blindman: That’s about all they live on on the reservation. Most people. Except the people who work for the welfare.

John Trudell: At Pine Ridge, didn’t the government set up new housing there several years back, three or four years ago?

Bernel Blindman: Yes, but most of them are set up for the people who work for the government because they can afford to pay for it.

Narration: Reyes was first inspired to research the impact of sound and music of the Alcatraz movement after taking several Berkeley classes — including one called Indigenous Musics in Unexpected Places — taught by John-Carlos Perea, who last year was a visiting associate professor in Berkeley’s Department of Music.

(Music: “Anamnesis” by John-Carlos Perea and Everardo Reyes)

Perea was born in Dulce, New Mexico, and grew up in the Bay Area.

John-Carlos Perea: The role of Indians of All Tribes in bringing in an intertribal American Indian voice to that time period in the Bay Area — that was central to me growing up, right? In terms of, I would hear people talk about Alcatraz. I would hear people refer to the importance of Alcatraz.

Narration: Perea is chair and associate professor of American Indian studies in the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University, where he was an undergraduate student in the 1990s. He remembers watching footage of the activist-students speaking from Alcatraz.

John-Carlos Perea: And being so incredibly brilliant in showing what you can do, not just with academics, but with culture, with humor, with art. They showed a kind of change and continued to show, for me, a kind of change that I very much identify with.

(Music fades)

Ethnomusicologist John-Carlos Perea was a visiting associate professor in UC Berkeley’s Department of Music last year. This year, he is continuing his collaborative work on the Berkeley campus with the Center for New Music and Audio Technologies. (Photo by Brandon James Yung)

Narration: Perea earned his master’s and doctorate in music from UC Berkeley in 2005 and 2009, respectively. He’s part of the third generation of Native-identifying students in the country to earn a music research Ph.D., along with his wife, Jessica Bissett Perea, a professor of Native American studies at UC Davis.

John-Carlos Perea: That’s just the Ph.D., right? If we went back further, and we looked at individuals who both came before us, who were working with some of the folks that are considered founders of the field, but who don’t get the credit in the same way. For example, thinking about folks like Francis La Flesche, as just one person, then we have many more generations who have come before us, in terms of who have participated.

But just in terms of institutional history, being in a department and pursuing these degrees, we understand, as far as the research we’ve done so far, that we’re only the third generation of Native-identified people with music research Ph.D.s.

Narration: Perea says music was central in creating intertribal connections on Alcatraz and in sharing the experiences of American Indians in the U.S.

John-Carlos Perea: Buffy Sainte-Marie singing about “Now that the Buffalo’s Gone” and those songs in that time period for her, they were historical documents. She was writing about what was going on. And then she was getting on stage and singing it. She was playing a song, but she was also doing the news, right? I mean, she was literally, you know, telling people what was going on.

Narration: For Grammy Award-winner Perea, who this year is continuing his collaborative work on the Berkeley campus with the Center for New Music and Audio Technologies, says creating and performing music today isn’t about leaving the past behind, but adding to it — remembering the stories of those who came before him and building on those stories. Then, sharing the stories with others.

(Music: John-Carlos Perea on cedar flute and Everardo Reyes on guitar)

Last spring, Perea and Reyes performed together in Hertz Hall at Berkeley — Perea on the cedar flute and Reyes on the guitar — as part of the music department’s 69th Annual Noon Concert Series.

John-Carlos Perea: I have an auntie who once said to me, “When you get up there, you’re up there with all the people in the past, even the people you don’t know who made it possible for you to be here and who, in some cases, died for you to be here.”

We have responsibilities to continue remembering, continue telling those stories, to continue learning new stories and to continue making sure those become a part — but again, as an accumulative process, right? We’ve got to try to remember as much as we can. It’s always going to be incomplete, which is why we need each other, right? Because in that sense, those different energies coming together allow for that greater understanding.

Narration: It’s what Reyes aims to do with his research — to remember the stories of the activists on Alcatraz, and to explore how music, radio and other sounds from the occupation influenced and continue to influence Indigenous activism and laws concerning Indian tribal policy today.

(Music fades)

The occupation of Alcatraz ended after 19 months on June 11, 1971. Leadership struggles and interlopers not dedicated to the cause were some of the problems that led to the protest’s decline. At the end, the federal government removed the last 15 or so protesters still on the island.

(Music: “Betty Dear” by Blue Dot Sessions)

Although the occupiers weren’t granted ownership of the island, the protest — which people could follow by listening to “Radio Free Alcatraz” — was a catalyst for decades of Indigenous activism and was a turning point toward Native American self-determination.

In 1975, President Nixon ended the termination laws and implemented the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, giving back tribes’ rights to govern themselves. He also funded nationwide policies for Indian tribes, which recovered millions of their acres of land.

Many of the activists involved in the occupation of Alcatraz went on to participate in other demonstrations and actions, particularly within the American Indian Movement.

In 2016, Indigenous protesters stopped the construction — at least, for now — of the Dakota Access Pipeline through unceded Native lands on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. LaNada War Jack has said the protest was representative of the spirit of resistance on Alcatraz decades before.

The fight for Indigenous rights, says Reyes, is far from over. And the occupation of Alcatraz — in his view — hasn’t necessarily ended.

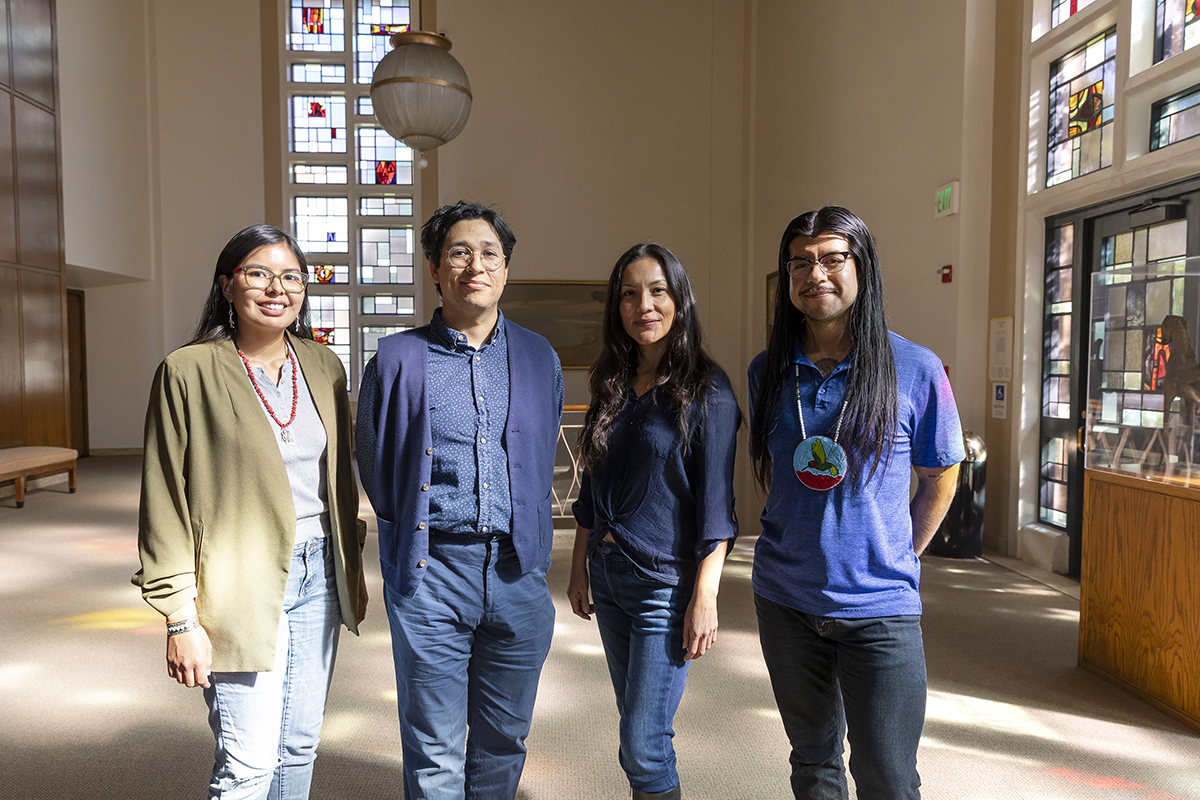

From left: Graduate students Sierra Edd, Everardo Reyes, Lissett Bastidas and Valentin Sierra are in the Indigenous Sound Studies working group on campus. Reyes and Edd started the group in 2020 to make a space for Indigenous scholars to talk about the intersection of sound, law, performance, gender, sexuality and other areas of study. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Everardo Reyes: There’s still a lot of activism happening around it. And, you know, there’s a fine line between activism and research sometimes, right? Or, sometimes there isn’t. And so, it’s hard to know or hard to say: Could Alcatraz happen again? I’m not completely convinced that Alcatraz is complete, you know, that it’s over, right? I still think it’s an ongoing occupation. And yeah, who’s to say Alcatraz won’t happen again? And learn from those lessons and learn from a lot of the elders and people who were there about what worked and what didn’t work and finally complete and finish what a lot of activists started out doing.

Narration: Every year since 1975, Indigenous people and allies have gone back to Alcatraz Island to participate in a sunrise ceremony to honor the memory of the 1969 stand.

(Music: “Hey, Little Bird” by Buffy Sainte-Marie)

Lyrics:

Hey, little bird

I remember you

You and your dreams up higher than you could fly

I remember you

Hey, little bird

Perched in the southern sun

Those were the days when your feathers were new

And I remember you

Little bird now you know where you’re at

Now the clouds are your habitat

But more than that we meet again and you’re still my friend

So, little bird, the times have changed considerably

I am a thrush now and you are a peacock indeed

So flash your colors and I will sing

Glide into time with the moon on your wing

Little bird, little bird, little bird

(Music fades down)

Narration: I’m Anne Brice, and this is Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs at UC Berkeley. If you enjoy Berkeley Voices, tell a friend about us — it really helps get the word out. And you can follow us wherever you listen to your podcasts. You can find all of our podcast episodes with transcripts and photos on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

(Music comes back up)

Lyrics:

Like a gull of the sea, your resting place

Can be heaven or countless oceans far from me

So, little bird, take my blessings to the stars above you

And scatter my wishes to the ones who love you

Take off often on a trip transcendent

And sink in the waves and then rise resplendent

Fly with your friends in a “V” formation

And sing to your flocks from your vantage station

Out in the stars beyond hell’s dominion

And rest at my feet in between migrations

Little bird, I remember you

Hey, little bird, I remember you

(Music fades)

Listen to other Berkeley Voices episodes: