Artist Eniola Fakile asks: What if a hamburger had feelings?

For the graduate student in art practice, her creations begin with questions, which lead to more questions, which take on lives of their own in a whole new universe of meaning

November 23, 2022

For the graduate student in art practice, her creations begin with questions, which lead to more questions, which take on lives of their own in a whole new universe of meaning

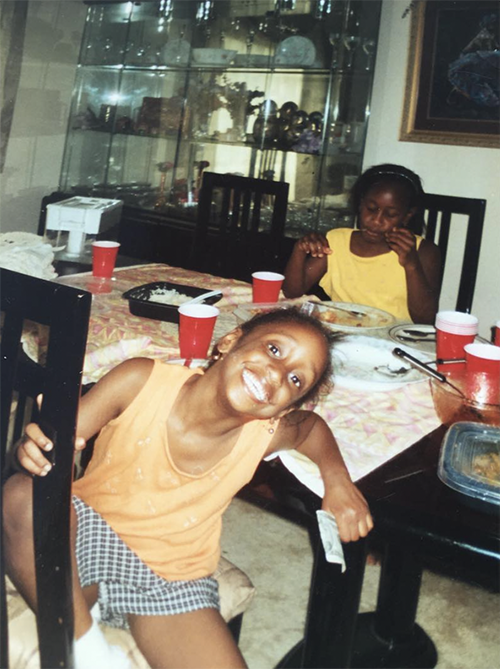

Eniola Fakile (pictured) is a second-year Master of Fine Arts student in UC Berkeley’s Department of Art Practice. This photo is from her series Mo ṣe fun e (I did it for you).

Eniola Fakile’s creations live in another world.

Fakile is a photographer. A performance artist. A filmmaker. A sculptor. A costume designer. She works in textiles, ready-made objects and assemblage. She’s not constrained by what has been or should be. Instead, she expands outward to see how far she can go. When an idea flashes in her mind, she imagines a new universe in which that idea, that creation, lives.

“I’m addicted to making things complicated,” she says. “I can never make something basic and easy. I like chaos of my own making because I made it.”

She builds sculptures. Some that people wear — and that she wears — and often posed meticulously. The harder the costumes are to build, the better. They might be made of fuzzy, neon-colored fabric. Or long, fluffy wigs. Or cotton balls and beads and crumpled tissue paper. Right now, she’s trying to figure out how to build a dress out of concrete — with an emphasis on the word “try,” she says.

As a Master of Fine Arts student in the Department of Art Practice, she says she feels encouraged by the faculty to go further, to push herself into new depths of self-exploration. It’s something she has been compelled to do since she was a kid — to put herself and her ideas out into the world, no matter how painful it might be.

Berkeley News spoke with Fakile about the process of creating art — “It’s 0.1% bravery and the rest is, like, I need to get it out,” she says — and how she’s learning to accept her wide-open nature, even when she doesn’t want to.

Berkeley News: Where did you grow up and what was your childhood like?

Fakile grew up with her parents and older sister in Stone Mountain, Georgia. “I wasn’t the kid who everyone was like, ‘Oh, they’re going to be an artist.’ I just did weird stuff. I liked to play outside, and I liked to talk to trees, play in the dirt.” (Photo courtesy of Eniola Fakile)

Eniola Fakile: I grew up in Stone Mountain, Georgia. I have two lovely immigrant parents who would do anything for me. My parents are from Nigeria. Even though I was born in America, the vibe in my house was like, “Don’t forget that you’re Nigerian. Don’t forget culture and family.” I’m exactly the same as how I was when I was a kid. I wasn’t the kid who everyone was like, “Oh, they’re going to be an artist.” I just did weird stuff. I liked to play outside, and I liked to talk to trees, play in the dirt. I was a bubbly kid. I cried a lot. I still do.

Have you always been interested in creating art?

I feel like I’ve always been doing art. I had an active imagination as a kid. The first time I really got into it was my freshman year of high school. My parents got me my first digital camera when I was a freshman in high school. It was this basic little point-and-shoot thing. I always had my camera with me. I was always taking photos. I took photos of my friends. I took endless photos of trees. I took photos of my feet. I took photos of my hands. I took photos of food. I just really wanted to reintroduce myself to the world through a camera lens.

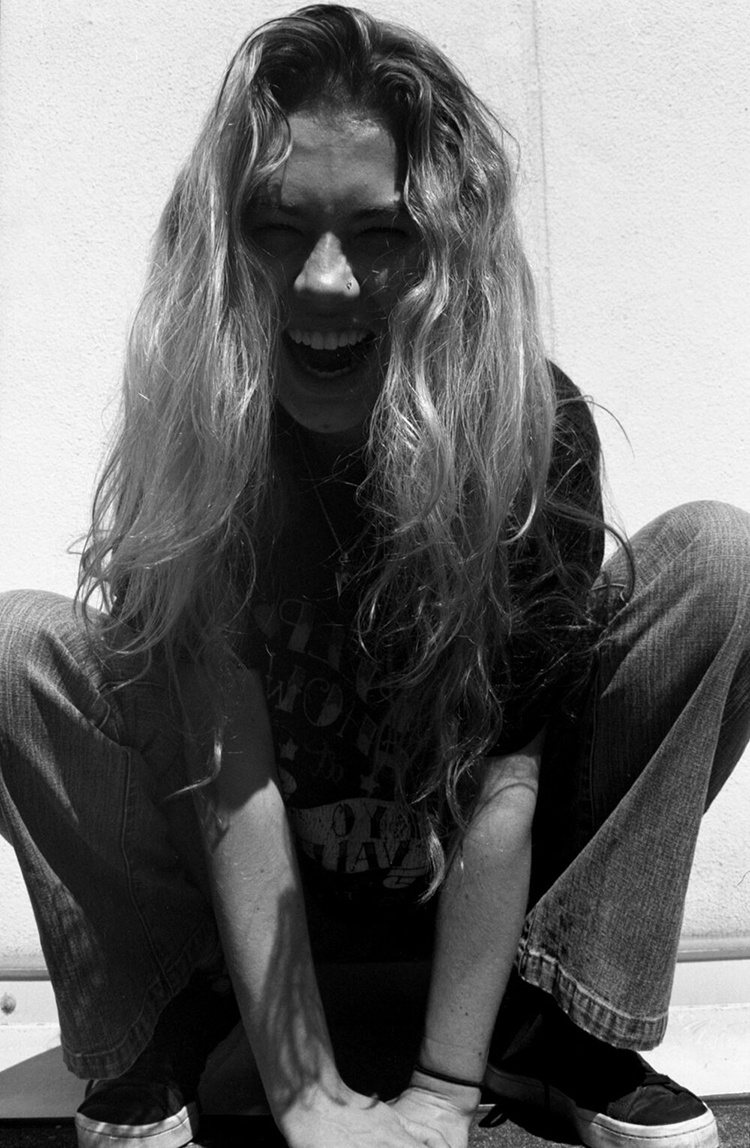

Photo by Eniola Fakile. As a sophomore in high school, Fakile took her first film photography class. “I fell in love with how physical of a practice it is,” she says. See other photos from her Black & White Film series.

As a sophomore, I took a film photography class. I fell in love with how physical of a practice it is. It’s learning how to handle things with care, working with chemicals, going out and making mistakes, going out again, making it better.

Now you shoot film in bigger formats. Why?

When you’re in the darkroom, you’re not only developing film, but you’re making prints, as well. What I love about large format is you can print really big images without losing any quality. Each digital camera you buy has a sensor that’s a certain size, so when you try to print bigger than what the sensor is capable of, then it starts to blur. But with a large-format camera, I could print as big as my apartment, and it would be fine. There’s nothing compared to the beauty and grace of a large-format camera.

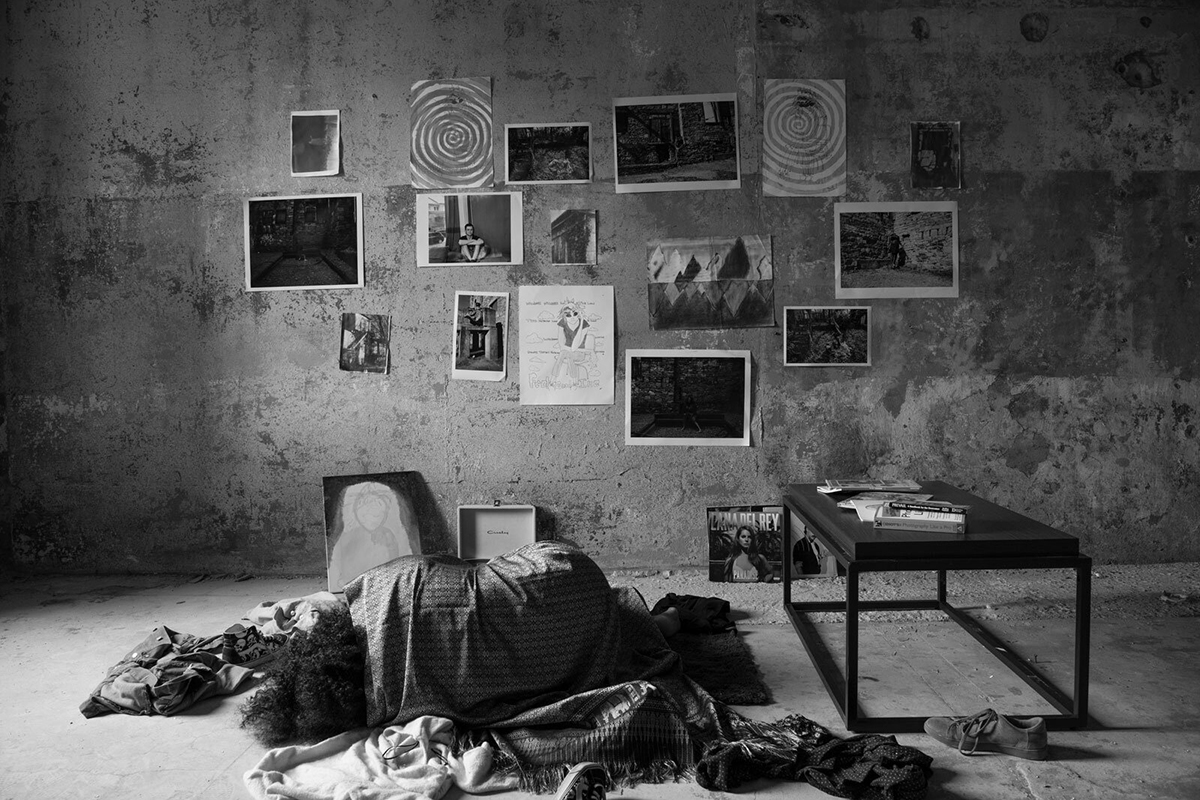

In your portfolio on your website, there are photos of you, often wearing your costumes and posed in different places outdoors. There’s one photo of you that’s part of a series — you’re in what looks like an abandoned warehouse, where you’re lying on a concrete floor with photos taped to the wall. It feels lonely and like we’re seeing a private moment, and I’m so curious what you were going through when you were creating that photo and series.

That series, where I’m lying in front of a wall with the table, it’s all about how I got in this really bad car accident when I was younger. And I feel like when you’re in your early 20s, you feel like, “I’m never going to die!” Until something happens and you’re like, “Oh, my God. I’m so close to death all the time.” And it really freaked me out so much. I was having an existential crisis every other day.

So, I made this artwork about how I feel, like how I’m trying to make myself comfortable in these uncomfortable spaces, these places abandoned by time. Because that’s going to be me one day. This place is old and gross, and it’s gone and deserted. But however many years ago, it was alive and full of people and stories and energy. And now it’s just gone. And that’s going to be me one day. So, I tried to figure out how to make a home there and accept the fact that these things happen. Even if now isn’t my time, my time is coming, so set up shop and get comfy with the whole point of all of that.

Self-portrait by Eniola Fakile. This photo is part of a self-portrait series that Fakile created following a car accident she was in. “I feel like when you’re in your early 20s, you feel like, ‘I’m never going to die!’ Until something happens and you’re like, ‘Oh, my God. I’m so close to death all the time.'”

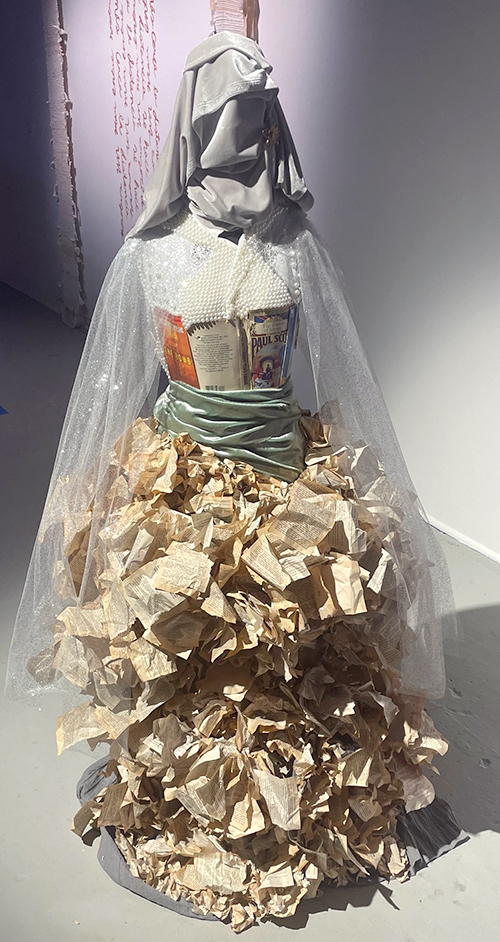

You also created a sculpture of your mom. Can you describe the piece and what it means to you?

“Mom” by Eniola Fakile

There’s a sculpture that I call “Mom.” It isn’t really a representation of her, exactly; it’s a representation of our relationship. It’s how I feel about her, how she feels about me, the things that we’ve been through, all thrown into her [sculpture] body. I wanted to choose a design that was classical, in the sense that it reminded me of old Hollywood, because I think my mom is classic 1950s, you know, wearing headscarves everywhere.

I fashioned the bottom of her dress out of this book paper, because when I was growing up, books were such a big part of my mom’s life — at least that’s what I thought as a kid. And I wasn’t allowed to read some of them just because they were grown-up books. And I hated that there was this piece of her that I couldn’t have.

Initially, when I was making the bottom of the dress, you know, you rip the pages out, you ball them up, and then you stick them together, and it makes this beautiful round shape at the bottom. I thought that I was doing her love of reading justice by making the dress out of paper, but then I realized that I was destroying a representation of what she loved, but also using it as a way to build something else that she and I can both share.

I put pearls all over it and things that shine and sparkle. Her head is a scarf. There’s a really beautiful flower brooch, and the whole thing is made out of a lab coat because my mom is a scientist. She loves that piece so much. She was like, “Oh, you made me look so beautiful.” And I’m like, “It’s not just you; it’s us.”

I love your video series. There are four videos — each one digs a little deeper into who you are. The first is titled, “An Introduction Into Who I am”; the second is, “More of Who I am. More of What I am”; then, “Digging Deeper, I’m Almost There”; and the last is called, “The Last Piece.” Is it meant to be a progression of you, showing a little bit more of yourself every time?

What do you think?

I think so — because at the beginning, there are little moments, little slices of life where you’re showing your daily existence: You’re dumping out a box of Ikea furniture that you have to assemble, like, “Here we go.” It’s so relatable. Then, you keep going, and toward the end, there are a lot of shots of you in the shower talking about what’s on your mind, about being a Black woman and how that feels for you. So, for me, it did feel like you were going deeper and deeper each time. But I’m curious if that was your intention.

Well, I think it is a progression. With each video, I wanted to dig deeper, but then, I also wanted the filming to get better. So, I was trying to progress as a videomaker. I made it over a year, and during that time, I started to become more and more comfortable with myself in front of the camera, talking about these things. And I’m always trying to be really careful about how I talk about being Black in my work because the way I feel about it is complicated.

Don’t get me wrong — I love being Black. But I feel like I want to make work about being Black without being exclusionary. So, I try to make work with little markers that I know other Black people can identify with, but then also everyday things that I know other people will respond to, so that it’s work that anyone can feel connected to. But especially Black people.

So, the series is about all those things. It’s about me as a Black woman dealing with my body image issues or how to deal with my hair. But it is also about me as a person dealing with the stress of everyday life, imposter syndrome, not feeling like I’m good enough. All of those things.

Costume and photo by Eniola Fakile.

There’s a part in one video where you’re in a conversation with someone, and you’re talking about how open you are and maybe you shouldn’t be, and that you should protect yourself more. Is that a driving force of your artwork — feeling compelled to share who you are even when it feels like a big risk?

Yeah. I’m glad you picked up on that because even when I watch that specific video, I hate it so much because I’m like, “Take your own advice.” It’s something that I struggle with so much. It’s a very distinctive quality that I have. I’m just so open all the time, and I really wish I weren’t. But I’ve come to the conclusion that that’s how I am. That’s also how the work is made.

Especially with some of the work that I made, that was recently in a show at SOMArts. There are different pictures of me wearing a cloak made out of crochet and different pictures of my face and body. Some of them are naked, some of them are clothed — I’m crying in different positions. And people really praised me for being vulnerable. They’re like, “Oh, my God. I could never do that. You’re so brave and strong.” And I’m like, “I’m not doing these things because I’m brave. I need to get it out.”

That’s how the work manifests itself: Even if it makes me uncomfortable, I respect the work too much to keep it hidden away. Once it gets out of my body and takes its own physical form, I respect it as its own being.

How do you approach creating art? Once you get an idea, where do you begin?

Every time I start a new series of work, I buy a journal, and I write down what I want to talk about. The process involves a lot of crying. It involves watching the same things over and over again to get the design juices flowing. Like, I’ll watch New Girl over and over again. I’ll watch Cruella — love that movie. The Devil Wears Prada. There’s a show called A Discovery of Witches with a season set in Elizabethan England.

When I get an idea for a sculpture or costume or whatever you want to call them — I still don’t have a name for them — it’s like a quick flash in my mind. I’ll do a really quick, messy sketch. Then, I try my best to build it. And it changes along the way.

My ideas manifest out of everyday things, like a hamburger. I’ll think: What is a hamburger? What if that hamburger had feelings? How do I turn that into a shoe? It sounds ridiculous. It involves a lot of fantasy and imagination, and I love doing it.

See more of Fakile’s work on her website and Instagram page.