To watch or not to watch? Berkeley expert’s tips on viewing graphic video

Alexa Koenig, co-director of Berkeley Law's Human Rights Center, talks about viewing — and how to view — violence online, such as Tyre Nichols' beating.

January 27, 2023

Violent videos, such as the one released today by Memphis law enforcement of Tyre Nichols being brutally beaten by police officers, should be viewed, if at all, with care, says Alexa Koenig, a faculty expert on psychological trauma and resiliency. (iStock photo)

A video was released today by Memphis, Tennessee, law enforcement officials that shows police severely beating Tyre Nichols, a 29-year-old Black man, after a Jan. 7 traffic stop. He died three days later.

Alexa Koenig is co-director of Berkeley Law’s Human Rights Center, which investigates war crimes and other serious violations of human rights with innovative technologies and scientific advancements. Her expertise includes trauma and resiliency in human rights work, and she co-founded the Human Rights Center Investigations Lab, where students are trained to mine videos on social media for suspected human rights violations or war crimes — and how to do so safely, both in terms of psychosocial security and cybersecurity.

Berkeley News spoke with Koenig about the role video plays in police brutality cases and how things have changed since the video of George Floyd’s murder in police custody on May 25, 2020, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. She also offered suggestions for safely viewing traumatic videos online.

Her book, Graphic: Trauma and Meaning in Our Online Lives, co-authored with Andrea Lampros, a Human Rights Center research fellow and communications director at the Berkeley School of Education, will be out in June from Cambridge University Press.

Alexa Koenig is co-director of the Human Rights Center at Berkeley Law. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Berkeley News: It’s been two-plus years since the murder of George Floyd and the video that served as a catalyst for social movements. What are you thinking about at this moment, and where we are societally, as we anticipate viewing another traumatic video of police violence?

Alexa Koenig: What I’m thinking about is how, within our communities and as a broader national community, we’re both raw and increasingly numb, even before we witness this. And I think having that as a baseline is a challenge for any society.

We are under extraordinary stress, given the pandemic we’ve all been living through and trying to figure out this new time that we’re all in. That cumulative stress that we have all collectively been experiencing over the last couple of years has left us in a place where we are already often feeling at our max. Whenever you are already in a very stressed and depleted place, to have a video like this come out that reflects some of the worst things that human beings can do to each other, from what I’ve heard about that video, we’re already not in a great place to be able to process and to handle the emotional onslaught that rightfully we all feel when we see something that is such a grave injustice.

One of the things that we’ve been learning in our book is some of the ways that people can take care of themselves, their families and their communities, while ideally also dealing with the social injustice of an incident like this. One of our big goals as human rights practitioners at Berkeley Law is to think through, “How do we make sure that people don’t just turn away from the painful things that are happening in our world but are actually engaging with it and constantly striving to make the world better for those who are suffering the most?” and doing that at the same time that we protect ourselves, so that we have the resilience and the fortitude to be able to continue that fight.

When these kinds of videos come out, they take a psychological toll. And I think that toll can either be constructive or destructive. The question becomes really how can we be mindful of the ways that we can prioritize the former and minimize the latter?

Resiliency techniques used at Berkeley’s Human Rights Center Investigations Lab, where students often view citizen videos that include graphic imagery from war zones around the world, include taking regular breaks from work — to reduce stress and exposure to troubling material — and reflecting on the meaning of their work, to stay motivated. (Photo by Andrea Lampros)

Your forthcoming book delves into your team’s work with the Human Rights Investigations Lab and includes coping strategies for viewing trauma around the world. What strategies have you found that we might all benefit from?

I think there are a few things that we learned that are important for people to think through as they gear up to watch a video like the one that we know is coming.

The first part is having awareness of yourself and your baseline functioning. So for a one-off horrific video, this may not be quite as relevant. But for people who are watching graphic videos repeatedly, or who are working in social justice and may come across a lot of these videos, just knowing how you usually sleep, how much you eat, how much you work out can be helpful. And then really tracking if, after watching a video like this, or multiple videos, or reading the news, you start to slip. That can be a sign that you’re beginning to be negatively affected in your resilience and your ability to process this information.

A second thing is awareness of what particularly affects you and what particularly affects the people around you. While we are all affected by violent graphic imagery biologically in very similar ways, the psychological side of it is impacted by our personal experiences and identities.

For example, if you are someone who has been harassed or beaten by police, you have a very different relationship to the video we’re about to collectively witness than someone who has never had a negative interaction with the police. It can easily retrigger your own experiences of trauma. On the one hand, you may find that watching it actually brings you closer in solidarity to others who’ve experienced violations like that. But for many people, it may bring back memories that are very hard to process over the weekend.

Knowing and having the awareness of what you can do to restore yourself can help people avoid some of the more negative numbing behaviors, like drinking a lot, using drugs, sleeping a lot, as opposed to the things that bring you kind of a healthier sense of pleasure, like talking with other people or going for hikes and being outside.

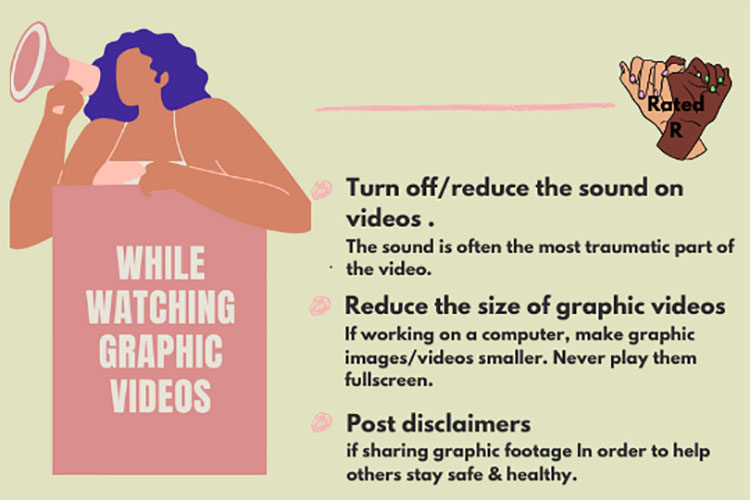

A webpage from Rated R, a site created by Berkeley alumnae trained at the Human Rights Center Investigations Lab, gives safer viewing tips for preparing to watch potentially distressing news videos on social media. (Image by Pearlé Nwaezeigwe)

Because of the toxicity of the cruelty, we sometimes think of that exposure as similar to exposure to toxic waste. Which part of your home do you not want contaminated, or your workplace, when you see this? What are the spaces that you need to safeguard? I would not recommend people watch this video while scrolling mindlessly on their phone in bed or on their laptop or late at night. The best practice for people who do this professionally is to sit at a desk. You want to view it somewhere that you feel like you’re in almost a professional or analytical capacity, and are prepared. You take a deep breath before watching it. And then watch it deliberately and intentionally in that space.

We also know a sense of surprise can be a tough one. Ideally, if you see the video on YouTube, for example, you can scroll thumbnails and get a sense of what you’re about to see without having the full resonance of the audio being loud and the video being large. We know that preparing your brain for what comes next can be a protective element, so that you are eliminating that aspect of surprise.

And a lot of professionals will actually watch the video first with the sound off or the sound down. Neuroscientists have shown that so much of the emotive content is in the auditory component of a video. It’s in the person’s pleading for their life or the mother screaming for their child. That’s what gets under our skin and is often very difficult to shake. So don’t play it as loud as you can. Ideally, don’t watch it on full screen or on a large screen TV. Bring it down to more of a human scale, or smaller, so that you are able to process that a little more effectively.

The other thing to think about is the people that you might share the video with. So let’s say you’ve watched it, and you want to bring greater awareness to what happened. When you’re sharing something like this, it’s important to not just share it mindlessly, like, “You’ve got to see this!” it can help the recipient to actually say to the person, “You’ve got to see this video, it’s of X, Y and Z. It’s a man being beaten by five police officers. It’s pretty graphic.” That will at least allow that person to make a conscious choice about when, where and even whether they want to watch the video in the first place.

A lot of the people that we have interviewed have said that they chose not to watch the video of George Floyd’s killing for a whole host of reasons, even though they are people who care deeply about social justice. Some of them said they didn’t need to see another killing of a Black man to know that violence against Black populations is very real in our country. And they felt that it was almost exploitive to do so. Some people have talked about “war porn” in the context of watching conflict videos, that it was almost exploitive to watch Floyd be killed in such a brutal way.

Sometimes giving yourself permission not to watch, or to read only secondhand materials or experience more packaged reporting, as opposed to the raw, full video itself, can be a way to ensure you’re still informed, while you protect yourself.

RowVaughn Wells, mother of Tyre Nichols, a 29-year-old man who died Jan. 10, 2023, after being beaten by Memphis police officers, smiles at supporters at the conclusion of a candlelight vigil for her son. (AP photo by Gerald Herbert)

Do you think the video of the murder of George Floyd changed the paradigm of on-camera police violence? And to that end, do you think psychologically we are in a different space now to view something like this then maybe we were three years ago?

Absolutely. In a few different ways.

One, I think we are probably more likely to come across videos like this. There’s such a proliferation of ways to access digital material that we stumble upon these things, even when we’re not actively seeking them out. One thing that I would recommend for a lot of people who use social media is to turn off autoplay on all of your platforms, if you don’t want to be shocked by particularly graphic material these days and want to make conscious decisions about what you view and when and how you view it.

The world has shifted to online witnessing of so much information, particularly during the shutdown of the pandemic, that as we see these videos come out one after the other, it’s easy to lose our sense of collective hope for change. That can lead to this kind of mass depression. It also can feel like these things are out of our control, and there’s nothing that we can do. And that can lead to a collective sense of anxiety that can really begin to interfere in a lot of aspects of our lives that are not directly related to social justice or online witnessing.

One task is to think about how we retain hope or generate hope. Can we see little wins in the fact that we are all condemning this video? That there is widespread condemnation of it? That there are growing calls for reform?

And then, on the control side, how can we contribute to those fights for reform — whether it’s participating in nonviolent protest, or it’s writing to a congressperson, or it’s educating others in our communities about the ways we may take action, or brainstorming that action, educating ourselves where we have gaps in our own knowledge of certain experiences. And then really thinking about what our responsibility is to help to address tragedies like these and help to minimize their frequency.

Vicarious, or secondary, trauma is indirect exposure to a horrifying event that can cause emotional, behavioral, physiological, cognitive and spiritual symptoms such as grief, anxiety, nightmares, negativity, cynicism, substance abuse, physical pain and loss of hope and purpose. (Photo by Monica Haulman)

Given the criminal case in Memphis and the apparent role that video has played and might play in the near future, what are you thinking about in terms of the prosecution, and the ways that video contributes to such a case?

A couple of things. On the more overarching level is the long history of the ways that graphic imagery has often helped spark social change. So going back to some of the slavery images that come out of the Civil War and the beating of former slaves, to Emmett Till, who was killed in the South in the 1950s, to Rodney King, up through some of the stuff that we’ve seen with Abu Ghraib. We’ve got Vietnam. Ukraine has been another space where visual witnessing has led to international outrage.

This video, from the sounds of it, is going to take its own place in that long history. But I think the introduction of video in the courtroom is also a very positive development. There was a lot of room before videos like these for there to be a “he said, he said” or “he said, she said” phenomena. But witnesses can be fallible in their memory, and they can be discredited, and they can ultimately be painted in a negative light. It’s helpful to have information that corroborates their testimony.

We all trust what we see with our eyes. So having something so visual, connected to the resonance of the auditory material, means that we will have a different emotional connection to the testimony than we would otherwise.

Do you plan to watch the video? Why or why not?

I do plan to watch the video. In my position as co-director of the Human Rights Center and as someone who supervises both students and professionals who are likely to see the video, it’s important that I know what they’ve experienced so that I can support them — as well as support the broader social justice community that is responding and will continue to respond to atrocities like these. But I will watch the video at my desk, with the sound relatively low, ideally while there’s still daylight. And I will take the time to process what I’ve watched and think about my responsibility to take action, and how I can do so in ways that have positive impact, acknowledging that I’ve just witnessed the brutal beating of a fellow human being — not just move on to the next thing in my social media feed as if nothing important has happened.

What haven’t we discussed here today that you want to convey to the public?

Just that I’m so sorry that we’re here again and about to witness another video like this one. And I hope that we can all take a deep breath and think strategically and carefully about how we honor the memory of Tyre Nichols, and how we can take some positive steps forward.