Grad student Caleb Dawson: Do the things you love, in a community that loves you

Dawson leads Black Lives at Cal, an initiative to preserve the history of Black people at UC Berkeley

February 7, 2023

Graduate student Caleb Dawson is leading Black Lives at Cal, an initiative to preserve the history of Black people at UC Berkeley. (Illustration by Neil Freese)

This I’m a Berkeleyan was written as a first-person narrative from an interview with, and writings from, PhD. candidate in education, and leader of Black Lives At Cal, Caleb Dawson.

I am a Black feminist sociologist who brings critical theories of race, class and gender to bear on the study of universities and social action. As a Ph.D. candidate in UC Berkeley’s education school, what I love about my research is that I’m able to delve into some of these types of challenges Black folks experience in higher education.

But I also focus on what our community does to show up for each other — to be well.

Caleb Dawson with Berkeley undergrads and members of Black Lives at Cal at the Pacific Sociological Association meeting last year. (Photo courtesy of Caleb Dawson)

And that’s why being lead investigator of Berkeley’s Black Lives at Cal (BLAC) has been such a rewarding experience. I launched the multi-year initiative, in fall 2021, to research, preserve and publicize the legacy of Black people at UC Berkeley. We started with just me and three undergraduate students, and three semesters later we have grown to fund four graduate students who mentor 18 undergraduate research assistants for course credit through the Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program.

Our initiative emerges from a partnership between the African American Student Development Office and the Institute for the Study of Societal Issues, and we have been fortunate to have the support of the Department of African American Studies, Black Studies Collaboratory, Cal Black Alumni Association, Division of Equity and Inclusion, Big C Fund, Chancellor’s Office and more.

For us, Black history at Berkeley is not just a month to celebrate. It is our lived experience.

And our histories are worthy of careful and rigorous research. BLAC has given us an opportunity to make sure our community knows our history and that it is not hidden, minimized or misrepresented on this campus.

An elementary school photo of Caleb Dawson. (Photo courtesy of Caleb Dawson)

I was born in Seattle, Washington, the middle child of three brothers. My dad is a self-employed financial adviser from the Bay Area. My mom is an immigrant from Ethiopia who came to America to study biology at Sterling College in Kansas and is a social worker in public housing. They met in Washington, where our family would settle down.

Growing up in South King County, I was raised to appreciate my Black community. My grandmother was a community health nurse trained at UCSF who continues to mentor Black students with interests in the medical field, and my mother has been heavily involved in local government. I was encouraged to be civically-minded from a young age.

To pay it forward.

My parents also made sure that I knew being Black meant you had to have as many cards to play as possible in order to navigate and be taken seriously in a white supremacist society. So, having a quality education was stressed in our household.

My father made it clear to me that it wasn’t just the education you got, but the symbol that those degrees from well-known institutions have in society — especially for Black people, because our blackness works like a negative credential.

Our parents sacrificed a lot to send us to a private Christian school through elementary and middle schools, determined for us to know we are created with divine purpose. As a teenager, I went to Federal Way High School, a public school in Washington named after the city we lived in.

Dawson was featured on a local news broadcast in Seattle for his campaign to rebuild Federal Way High School in his hometown. (Photo courtesy of Caleb Dawson)

As a student, I excelled in most everything my teachers valued. Getting good grades and performing well in school was an expectation in our household. My mom, like a lot of immigrant mothers, always enthusiastically instilled in us that we had to get the highest degree possible. It didn’t matter what subject area, but it had to be some kind of doctorate.

And when it came to school, my parents really advocated to make sure we got the support in anything we needed whether that was mentors, after-school activities and/or volunteer opportunities.

I was always toward the top of my classes academically. And as president of the student body, I successfully campaigned for my school to be rebuilt, and I led major food drives to support our local food banks and a food pantry at my high school. And because I was seen as a “good” student/citizen, I felt like I was treated differently than other students of color.

Tokenized.

For some authority figures, I was the “good” and “exemplary” Black student who acted in an acceptable way. Black students weren’t seen as academically viable, so they saw me as less Black, and they put me on a pedestal that was actually very alienating.

I wasn’t interrogated for walking through the halls without a hall pass like my Black peers, and I was given academic opportunities and support that they didn’t have access to. The classic micro-aggression was the shock and spectacle that was made at times when I spoke. “Oh, wow, you’re so articulate,” they would say to me. As if Black people can’t be articulate?

It got to a point where I was tired of being their Black articulate student.

As a high school student Dawson said: “For some authority figures, I was the ‘good’ and ‘exemplary’ Black student who acted in an acceptable way.” (Photo courtesy of Caleb Dawson)

Looking back, I feel as though I was used in racist ways to disparage blackness and normalize whiteness. In some cases, I was construed as a “good Black” that could be held up to discipline and dehumanize other students as the “bad Blacks.” In other cases, I was regarded as not Black or even white because I was “good.” It was confusing and very uncomfortable to be treated as both the “good Black” and not Black.

Our school was very diverse, but I often was one of the only Black students in my advanced classes. I realized many Black students didn’t have the same resources of going to private school and having the same academic training that I got, despite having parents who wanted the best for them, too. Many were put on a learning track at a very young age that constrained their educational trajectories and didn’t take their learning seriously.

Still, like our high school mascot, we rose like eagles against the odds.

In 2013, when I graduated high school and moved on to Gonzaga University for my undergraduate studies, I took those experiences and perspective with me moving forward. And I identified education as a preferred site and a tool to mitigate suffering and improve local circumstances for disadvantaged communities.

Dawson celebrated with family at his graduation from Gonzaga University. (Photo courtesy of Caleb Dawson)

As Gonzaga’s first Black student body president in more than two decades, I successfully led initiatives to reform the university’s mission statement and create the Critical Race and Ethnic Studies Department. And to improve underrepresented students’ experiences, I hosted forums for peers, co-led professional development for professors and helped found the university’s diversity and inclusion committee.

I graduated with honors with a double major in sociology and economics, but not without recognizing that I needed more from higher education. I wanted to be a professor. But I also realized that the issues I wanted and needed to learn about were not always readily available in university curriculums, which were often Eurocentric.

And that was frustrating.

When I enrolled at UC Berkeley in fall 2017, I felt like it was a campus that had more opportunities for me to delve into academia relevant to my research interests. It was also refreshing to see that there was much more infrastructure for Black people on campus than I had experienced in the past.

There’s the Fannie Lou Hamer Black Resource Center, an African American Student Development Office and an African American Studies Department with many Black faculty. And I had never had a Black professor in my entire undergraduate studies.

Dawson with mentor and former UC Berkeley education school dean Prudence Carter in San Diego for the 2022 American Educational Research Association annual meeting. (Photo courtesy of Caleb Dawson)

I enrolled in graduate school as an advisee of sociologist Prudence Carter and Black studies scholar Michael Dumas in the Critical Studies of Race, Class, and Gender program. Those mentors helped develop several of my research projects that address diversity and opportunity amidst structural inequality, such as how college access is sometimes arranged to prey on low-income students for profit.

And although I was devastated by my mentors’ eventual departures from campus, my current dissertation committee and Black community at Berkeley have given me the support to continue to organize and delve deeper into my research.

As a Black Studies Collaboratory fellow with the African American Studies Department, I have received funding to focus more freely on advancing my dissertation project about anti-blackness and the equity work of Black people at UC Berkeley. More substantiatively, the fellowship has provided the ultimate incubating environment for me to contend carefully with the stakes of my research for Black people within and beyond the university.

On Feb. 8, with invited guests — Doctors Adia Harvey Wingfield and Bianca C. Williams — I will host a talk entitled, “Caught Caring: (Un)freedom and the Costs of Service Labor in the University,” as part of the Black Studies Collaboratory’s Spring Speaker Series. This fellowship has generously created the conditions for me to dream and scheme about the Black futures that are truly free.

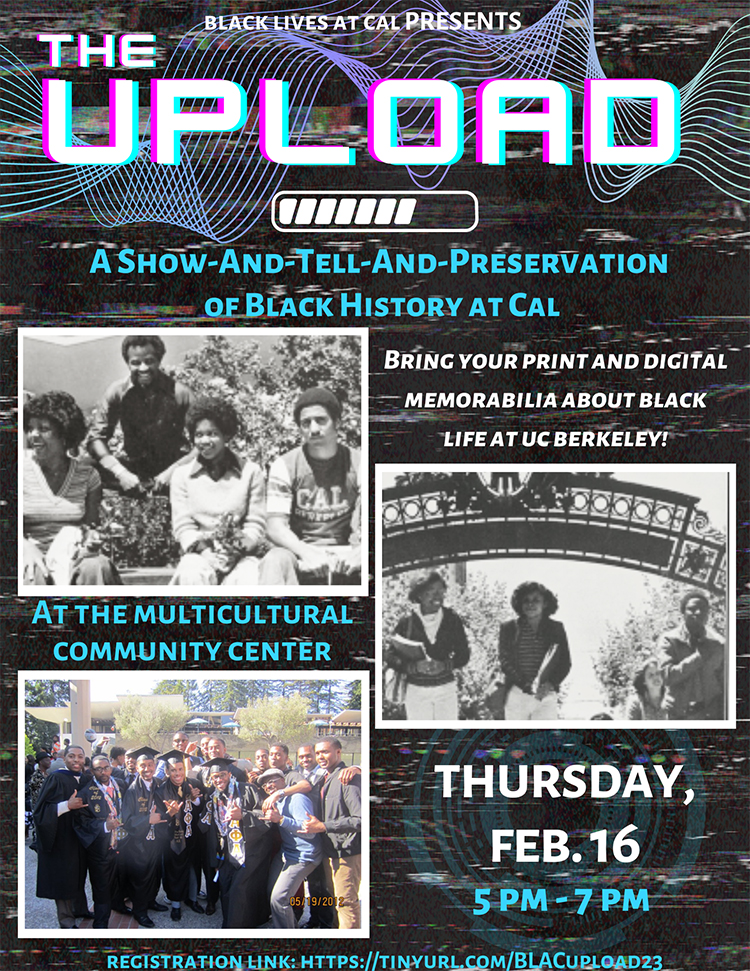

I have every intention to work towards that future and recreate the conditions for more people to dream with us. In fact, with Black Lives at Cal on Feb. 16 we’re inviting our community to bring their digital and print memorabilia to the Multicultural Community Center for a show-and-tell of Black history called “The Upload.”

Black Lives At Cal is one of those dreamy, world-building projects. We’re building a better future for Black people at Berkeley and beyond by taking seriously the history of those who have come before us and keeping record of history as it unfolds in the 21st century, whether that’s the history of Black student activism, award-winning teaching and scholarship, trend-setting milestones of alumni, or the everydayness of cultivating joy and community despite institutional and interpersonal racism.

We want to honor the past, preserve the present and advance Black futures. And how we do that is no less significant than what we do.

We have created this initiative about Black history by drawing on the expertise of graduate students to support our undergraduate students with their research and professional skills – students who are often overlooked for group projects, clubs and research opportunities. Plus, they get the benefit of connecting with current, former and future members of the Black community at Cal, as BLAC forms the glue that brings various groups and generations together.

I can hardly imagine something more beautiful than creating the conditions for Black people to do the things we love, for community, in a community that loves us.

Dawson with Berkeley alumni — (left to right) Blackbook University co-founder Ibrahim Baldé, retired administrator Ben Tucker and emeritus professor Vernard Lewis — at the Black Lives at Cal launch party in April 2022. “I can hardly imagine something more beautiful than creating the conditions for Black people to do the things we love, for community, in a community that loves us,” said Dawson. (Photo courtesy of Caleb Dawson)