UC Berkeley’s Moses Hall is unnamed; its namesake held racist beliefs

Bernard Moses, considered the UC's father of social sciences, held views that are incompatible with the university's guiding principles

February 7, 2023

The lettering on Moses Hall was removed this morning, Feb. 7, 2023, by a campus work crew prior to campus officials announcing the unnaming of the building due to the racist views of its namesake, Bernard Moses. (UC Berkeley photo by Julian Meyn)

Moses Hall today became the fifth building in University of California, Berkeley, history to lose its name because of the racist views of its namesake.

In a Dec. 5, 2022, letter to UC President Michael Drake requesting the unnaming of the hall that honored Bernard Moses, a prominent faculty member from 1875 to 1911, Chancellor Carol Christ wrote that “removing the Moses name from our campus — and acknowledging our historical ties to Bernard Moses — will help Berkeley recognize a challenging part of history while better supporting the diversity of today’s academic community.”

Drake approved on Jan. 13, 2023 the removal of the Moses name, which also is on a parking lot adjacent to the hall and is used in programming such as the campus’s Bernard Moses Memorial Lecture, established in 1937 by the UC president and the UC Regents. As of today, the building is temporarily being called Philosophy Hall.

At UC Berkeley, Boalt, LeConte and Barrows halls were stripped of their names in 2020; Kroeber Hall’s name was removed in 2021. The lettering on Moses Hall’s exterior was taken down this morning by a campus work crew.

Members of the Department of Philosophy, supported by the Institute of Governmental Studies and Global, International and Area Studies, analyzed Bernard Moses’ writings for evidence of racism. Then, three of them authored an unnaming proposal sent for consideration to the chancellor’s Building Name Review Committee. This photo was taken prior to the unnaming. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

The 1931 building houses the Department of Philosophy, Institute of Governmental Studies, and Global, International and Area Studies. Originally the Eshleman Memorial Publications Building, home to the Daily Californian and other student publications, it was renamed Moses Hall in 1965, when a new Eshleman Hall opened on Lower Sproul.

In their proposal to the chancellor’s Building Name Review Committee, which unanimously recommended to her the unnaming, the philosophy department’s graduate students, staff and faculty — with support from the building’s other units — noted the “intensity” of Moses’ racist and colonialist views.

“ … if any of the views held by Moses’ contemporaries deserve to be called ‘moderate,’ his would not be among them,” the 14-page proposal states. Further, it argues, Moses’ beliefs weren’t just personal, but woven into and explicitly defended in his academic work.

Retaining the name of Moses Hall “ … could reasonably be seen as an affront to students, instructors and staff of color,” the document continues. “The hurt that name has already caused to some in our community is what gave rise to this proposal.”

The unnaming, said Alva Noë, the chair of philosophy, “is an act of affirmation of the values of love and respect that are today the guiding principles of life here at the university.”

Current philosophy chair Alva Noë (left) and former chair Niko Kolodny stand outside former Moses Hall. It was unnamed today and will temporarily be called Philosophy Hall. (Photo by Brittany Hosea-Small)

Feelings of alienation in Moses Hall

In summer 2020, Professor Niko Kolodny, then-chair of the philosophy department, said he became aware via email that Moses’ name “had been deeply disturbing to several people of color with a home in the building who knew about Moses’ history.

“As the rest of our department read more, needless to say the sense of discomfort became more widespread. Were there other students, including undergraduates, who knew about Moses and felt similarly alienated by the name, but never said anything? I don’t know, and that is troubling in itself.”

Following an initial discussion in June 2020, about 20 members of the department divvied up and studied Moses’ major works, looking for evidence of racism, then wrote summaries that were completed in mid-February 2021. After that, the Moses Hall Name Review Committee was formed to review the synopses, along with a drafting subcommittee.

“The committee agreed unanimously, after reading the reports, to move forward with a proposal to unname Moses Hall,” said philosophy graduate student Milan Mossé, who was on the three-person subcommittee that then drafted the proposal.

The proposal was sent on May 26, 2021, to the chancellor’s Building Name Review Committee, which studied it and solicited and read more than 150 comments about it from the campus community before taking a vote. It sent its unanimous decision to Christ in a May 25, 2022, letter.

David Schaffer, the Hubbard Howe Jr. Distinguished Professor of Biochemical Engineering, is chair of the chancellor’s Building Name Review Committee. (Photo by Neil Freese)

David Schaffer, chair of the chancellor’s Building Name Review Committee, called the group’s proposal “scholarly and convincing.”

“The compelling evidence,” said Schaffer, professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, bioengineering and neuroscience, “comes from (Moses’) own published writings, which had a longstanding position that the Indigenous population in Latin America was genetically inferior to the colonial Spanish population. While belief in the genetic superiority of European-originating populations was certainly common at the time, this is clearly not consistent with the current values of our campus.”

Founder of Berkeley’s political science department

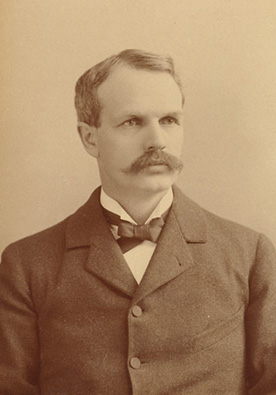

Bernard Moses was a prominent and influential faculty member in the early days of the University of California. He taught almost all of the campus’s economics, history and law courses during the first 15 years. (UC photo)

Bernard Moses was born in 1846 in Burlington, Connecticut. He attended the University of Michigan and the University of Heidelberg, earned a doctorate of laws degree, then began his teaching career in Michigan at Albion College. In 1875, he arrived at the University of California and for the next 15 years taught almost all of the campus’s early economics, history and jurisprudence courses.

In 1883, Moses created and chaired the former Department of History and Political Science, and in 1903, he established political science as a separate academic discipline and founded the Department of Political Science.

A preeminent authority on the history of imperial Spain and Latin America, Moses strove to understand economic history from the perspective of Latin American peoples and states, and he made frequent academic and official trips to and traveled extensively in Mexico and South America.

From 1900-1903, under William Howard Taft, who at the time was civil governor of the Philippines, Moses served on the Philippine Commission, which at first was the sole legislative body of the Philippines — then called the Philippine Islands — under U.S. control. In 1908, Moses was a delegate to the Pan American Scientific Congress in Chile, then in 1910, a member of the Fourth International Conference of American States in Buenos Aires. He also was assigned in 1910 as a minister plenipotentiary — a diplomatic agent given full powers to sign treaties or conventions — on a special mission to Chile.

On these trips, Moses acquired historical and political collections of materials on South America that he used after his retirement in 1911 to write about Hispanic American history.

The building formerly called Moses Hall will now temporarily be Philosophy Hall. (UC Berkeley photo by Julian Meyn)

Moses: ‘Blood’ causes racial differences

But in various published works, Moses also expressed racist views, particularly two: that races are differentiated from each other by inheritable physical, intellectual, aesthetic and moral characteristics, and that the white race is superior to all others.

Those perspectives conflict with both the assertion by chancellor’s Building Name Review Committee’s that the “legacy of a building’s namesake should be in alignment with the values and mission of the university” and with several of the Berkeley campus’s Principles of Community.

Evidence detailed in the philosophy department’s proposal reveals Moses’ belief that races are distinguishable by inheritable physical and mental characteristics — that race, as Moses often put it, is a matter of “blood.” Moses also believed that negative inheritable traits are associated with non-white races, and that positive characteristics are found in the white race.

“That is,” wrote the proposal co-authors, “he believed that non-white races are inferior to the white race.”

In “The Government of the United States, 1906,” Moses wrote, “The Spaniards, who settled Mexico and South America, intermarried with the Indians and as a consequence their descendants fell below the European standard.”

Moses Hall, pictured here before its name was removed, got that name in 1965. It opened in 1931 as the Eshleman Memorial Publications Building; when a new Eshleman Hall was built on Lower Sproul Plaza, Bernard Moses became the older building’s namesake. (Photo by Brittany Hosea Small)

Moses felt these differences among races explained the superiority, for example, of the English, who colonized America.

“The people of the United States have set out with the fundamental idea of equality which involves the abolition of race prejudice,” he wrote in “Results of the war between Russia and Japan,” “in spite of the fact that it is the preservation of this prejudice, or of race-respect, that has kept the English stock free from contamination of barbarian blood, and given its position in the world.

“It is, therefore, a matter of grave concern whether a nation in colonizing preserves its stock unmixed with lower elements or, becoming united with barbarians, leaves a posterity less effective than would have been descendants of unadulterated blood.”

Several passages in Moses’ writings highlight his belief that Indigenous heritage is an impediment to prosperity and progress. For example, he wrote, “Neither the Indian nor the mestizo was capable of originating and carrying on great enterprises,” in his book South America on the Eve of Emancipation (1898).

In Spain’s Declining Power in South America, 1730-1806, “the support Moses expresses … for the Jesuit project of educating Indigenous people in South America can only be seen as paternalistic,” the unnaming proposal states. The few Indigenous families that sent their sons to Jesuit schools “acquired a certain amount of elementary knowledge,” Moses wrote, “but difficulties arose when attempts were made to give them more advanced instruction. It was found that the barbarian was only a good beginner in learning.”

Only shadows remain of the words Moses Hall on the building’s north entrance. (UC Berkeley photo by Julian Meyn)

Intense white supremacist views

The racial superiority of the white race, Moses believed, underlies his identification of a “problem” that he discusses in several works, the philosophy department co-authors wrote, which, in Moses’ words, is how “the dominant nation of the superior race” should relate to “less developed peoples.”

The Moses Hall Name Review Committee report states that “ … the possible solutions (Moses) discusses as no longer available are the following: on one hand, exterminating non-white people or pushing them out, … and on the other hand, mingling of blood.

“Moses’ issue with the former possibilities seems to be practical rather than moral: The non-white inhabitants of an area are too numerous, or there is nowhere else for them to go. His objection to the latter is that it produces a ‘mongrel people’ so inferior to white people that it would take hundreds of years for the mongrel people to achieve the state of the white race.

“In other words, Moses rejects the latter on decidedly white supremacist grounds.”

Moses also wrote of the post-emancipation Southern U.S. and relations between whites and Black people, pointing out in his 1900 paper, “New Problems in the Study of Society,” that Black people “were not sufficiently civilized to be effective citizens,” the unnaming proposal states, and that it became necessary, in Moses’ words, to “meet the crimes of the barbarian with a method and a punishment that might be supposed to impress and deter the barbarian.”

The response, lynching, the proposal continues, “was not a way of dealing with ‘emergencies’ (i.e., immediate threats to civilization to which there were no legal remedies), but was rather a means of social control, a means of protecting the supremacy of white people and white culture.”

Moses’ perspective might have been common among white academics at the time, said the co-authors, “but it is at odds with the present values of the UC Berkeley community.”

Alex Mabanta, a Ph.D. student in jurisprudence and social policy, is the graduate student representative on the campus’s Building Name Review Committee. (UC Berkeley photo by Neil Freese)

Next steps: ‘an appropriate restorative approach’

In its recommendation to the chancellor, the Building Name Review Committee stressed that campus administrators should consider authorizing and providing a budget for a working group of faculty, staff and students, drawn from units housed in former Moses Hall, “to develop an appropriate, restorative approach to reckoning with the legacy of Bernard Moses, particularly in regard to communities of color, in the United States, Latin America and the Philippines.”

Alex Mabanta, a Ph. D. student in jurisprudence and social policy who is on that committee, said it’s important for Berkeley to “foster civic education across its landscape of public memory, including the construction of plaques, exhibits or murals that enrich and recontextualize collective knowledge of buildings and monuments from the perspectives of multiple parties.”

He said that Berkeley Law’s display, which was designed and installed in May 2021 following the decision to remove Boalt Hall’s name from its main classroom building, is a “highly-trafficked forum” that has facilitated conversations about racial justice and the Chinese Exclusion Act among law school students, staff, faculty, administrators, alumni and visitors. There is also a digital version of the Berkeley Law display.

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation has granted millions of dollars for universities nationwide to foster, narrate and uplift multiple histories and advance public dialogue, Mabanta added, and it might be helpful to the departments and units of unnamed buildings at Berkeley that each is tasked with creating a way to help its community reckon with a building namesake’s legacy.

But for today, and starting today, said Kolodny, “I hope that the building will feel more like the inclusive home for those who work and study there that it is supposed to be. More generally, I hope that it will make the campus’s commitment to the principles of diversity, equity and inclusion more consistently visible.”