Follow Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast about the people who make UC Berkeley the world-changing place that it is. Review us on Apple Podcasts.

See all Berkeley Voices episodes.

Yesterday at sunset marked the start of Ramadan, the ninth and holiest month of the Islamic calendar. For Ali Bhatti, a Ph.D. candidate in science and math education at UC Berkeley, it’s a time to remember what he’s thankful for.

“This is a month that has obligatory fasting within it,” says Bhatti “From about sunrise to sunset, you’re not eating, and you’re not drinking any water. … I try to flip those moments of hunger, try to flip those moments of thirst into a moment of consciousness, of awareness of something that you’ve been blessed with or something that you have.”

In this episode, Bhatti describes what Ramadan means to him. He also talks about how 9/11 shaped his childhood in New Jersey, finding his Muslim community at Berkeley and how Islam, and the support of his family and Berkeley community, helped him get through the hardest time of his life.

(This piece was written as a first-person narrative from an interview with Bhatti.)

Ali Bhatti (right) with him mom, Nabila. (Photo courtesy of Ali Bhatti)

Read a transcript of Berkeley Voices episode 109: Ali Bhatti on Ramadan and how his faith guided him through deep loss.

Anne Brice: This is Berkeley Voices. I’m Anne Brice.

[Music: “Spindash” by Blue Dot Sessions]

At sunset yesterday, on March 22, marked the start of Ramadan, the ninth and holiest month of the Islamic calendar. For Ali Bhatti, a Ph.D. candidate in science and math education at UC Berkeley, it’s a time to feel closer to God, to break habits and to remember what he’s thankful for. In this episode, Ali describes, in his own words, what Ramadan means to him. He also talks about how 9/11 shaped his childhood in New Jersey, finding his Muslim community at Berkeley and how Islam has helped him through the deepest loss of his life.

[Music fades out]

Anne Brice: Part 1: Fasting for Ramadan

Ali Bhatti: Really, one of the biggest physical expressions of being Muslim is fasting, is participating in the month of Ramadan. This is a month that has obligatory fasting within it. From about sunrise to sunset, you’re not eating, and you’re not drinking any water. It’s one of the pillars of Islam, one of the pillars of the religion. And this is a pillar that everyone who is healthy enough to do and who is able enough to do is required to do for the 30 days that are within Ramadan.

So, fasting is a physical — this is how I’ve always viewed it — it’s a physical representation of a very spiritual process that you’re trying to go through. And connecting the physical and spiritual is not easy. Oftentimes, it will just be a feeling of “I’m very hungry. I’m very thirsty.”

But spiritually, I think there’s a lot more going on, and that’s something that I’m, personally, on a journey of trying to reach.

[Music: “Aourourou” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Within the Quran, there’s a specific verse that states that fasting has been prescribed for you. And, to me, I start reflecting on that, like, “Why was it prescribed?”

Ultimately, the prescription is to be God-conscious, to be more conscious of God, because you try your best to think about God more during this month than any other time of year. Think about your blessings. Think about the things that you have, things that are a part of your life, the people, things like that. So, the God-consciousness starts to build up more and more.

And one of my personal habits is when I feel like, “I’m hungry,” or “I’m thirsty,” trying to think, “OK, what am I thankful for right now?” You know, “I’m really thankful that I’m here at Berkeley,” or “I’m in a home,” or things like that. Try to flip those moments of hunger, try to flip those moments of thirst into a moment of consciousness, of awareness of something that you’ve been blessed with or something that you have. So, that ends up being a personal practice of mine.

[Music fades out]

Anne Brice: Part 2: Growing up Muslim in New Jersey after 9/11

Ali Bhatti: I was actually born in Pakistan. I was born in a city called Gujranwala, Pakistan. I came here when I was a young kid. I was 2 or 3 years old. I came here with my parents, my mom and dad, and we moved to New Jersey, and I stayed there up until graduate school, which was 2019.

Ali (right) in Pakistan with his mom, Nabila; his dad, Obaid; and his older sister, Almas. Ali was born in Gujranwala, Pakistan, and moved to the U.S. with his family when he was 3. He grew up in New Jersey five miles from where 9/11 happened. (Photo courtesy of Ali Bhatti)

I grew up about five miles away from where 9/11 happened. And to grow up in the tri-state area as a practicing Muslim, someone with a Muslim name, there was a lot to go through in that process. It’s normal to go through some sort of growing periods of bullying and things like that. But it was very tough to be in a situation where something that I hold so deep and true to me, which is my faith and what I practice, for that to be front and center as, like, I am the Muslim kid in class. I am always the Muslim kid and the only Muslim kid in class. That ended up being a front and center thing that propagated throughout my education. And it really just kind of put me in a space where I just understood this idea of being othered or feeling like I don’t belong.

The biggest things that end up coming to my mind are, you know, just some of the bullying, some of the jokes. You know, you hear a watch beep, someone’s going to say, “Oh, is that a bomb that you planted?” Or something doesn’t go your way, someone will saying something like, “Oh, are you going to blow the school up now?” Or like when Osama bin Laden was killed, you know, “Sorry for your loss.”

[Music: “Idle Ways” by Blue Dot Sessions]

You know, as a kid, you just try to laugh with them, rather than saying, “Don’t make fun of me.” You kind of just try to (air quotes) “be cool” about it, if you will.

But eventually, at some point, you do want to take a stand, and you want to make clear that this is not something that you’re for or not something right to say. And I think, really, it just came down to being proactive about that, like, presenting myself and the things that I do and the way that I act in a way where hopefully someone would feel bad about making fun of me in that way.

The discussions at home were all about recognizing the fact that no matter what anyone says, you are who you are, and that is supported by the faith that you practice. And so, to see that perspective of, use this as an opportunity to better yourself and better the people around you and be a better Muslim.

[Music fades out]

As much as it was a pressure to feel like an example, it was a motivator to me. You know, partying or drinking or anything like that, those things, as normal as they seemed or as sort of rite of passage as they were, weren’t part of my growing up, that wasn’t part of who I was. If anything, it was something to really hold me and ground me in a way where I saw it as like, “OK, I am unique in this aspect of growing up as a teenager in America.”

Friday is generally a day to go out partying, but for us, it’s actually our holiest day. It’s the day that we go to the mosque and we have Friday prayers and we listen to a sermon. That’s the juxtaposition that ended up being a big part in my head of, like, “OK, I can see this as a characteristic of mine that differentiates me in a positive light in a way that is unique.” And I really started to take that on.

Anne Brice: Part 3: Five daily prayers

Ali Bhatti: There are five daily prayers within Islam. And one thing I’ll tell you is that this is something that I’ve grown to do more of. During my high school time, I didn’t pray during the day. I would kind of just make up those prayers when I came home. And that’s allowed. It’s acceptable. But for the most part, it’s preferred to pray them at the correct times, because those five daily prayers happen at specific times, and you have sort of windows to pray them.

Ali prays at his mosque in Berkeley. (Photo from a video by Stephen McNally for UC Berkeley’s Light the Way campaign)

The first prayer is before sunrise. It’s called fajr. There’s a specific call that says, “Prayer is better than sleep. Prayer is better than sleep.” Then, there are two prayers during the sunlight hours, pretty much an early afternoon prayer and a late afternoon prayer. Those are the ones that, if I’m on campus, usually I’ll have to find a room to pray in. And then, there’s a sunset prayer. And the last one is the night prayer.

Ultimately, the whole point is to just, again, have a remembrance of God during the day and throughout the day in these moments.

Once I came to Berkeley and was on my own, I felt like this would be something that would help me ground myself in something that I’m familiar with, but also something that brings me a sense of calm, a sense of spirituality, a sense of peace.

One of the things that’s difficult is when you’re praying, we’re praying in the Arabic language, and most Muslims don’t speak Arabic, actually. They don’t understand. They don’t have a vocabulary that is in Arabic. As a Pakistani, I speak Urdu. That’s our native language. It’s not Arabic, but we have to memorize in Arabic. We have to learn how to read Arabic. We have to learn how to recite Arabic. We don’t necessarily have to learn how to translate that into our language, unless you’re an Arab from an Arab country. But this is, again, one of the things that is something I’m trying to work on, a lot of Muslims try to work on, is to understand the Arabic that they’re speaking and praying in.

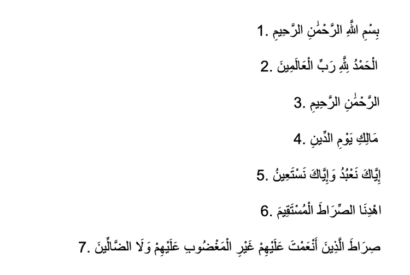

Every prayer has the opening chapter called fatiha (pictured).

Every prayer has the opening chapter. It’s called fatiha. It’s the opening chapter of the Quran. Every prayer requires that. It’s part of the requirement of a prayer. And then, after that, you can sort of choose verses that resonate with you, or verses that are on your mind, or verses you’re trying to memorize, things like that. But every Muslim has the opening memorized, so I’ll recite it here.

(Recites fatiha in Arabic)

Anne Brice: Part 4: Profound loss and how he moved through it

[Music: “Anippe” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ali Bhatti: My mom passed away in my first year of graduate school. Unexpectedly, tragically, she passed away, and I didn’t think I could continue with graduate school. I didn’t think it was possible to be that far away from home, all the way in New Jersey. My dad was alone. My sisters also live in different areas. I didn’t think it was possible to continue. And that was very, very difficult. It was undeniably the hardest moment of my life because of the instant nature and tragic nature of it.

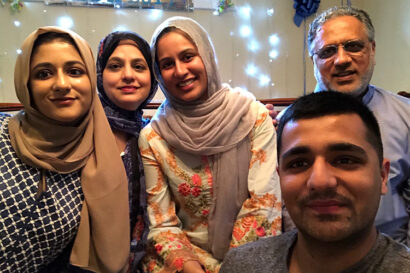

Ali with his mom, Nabila; his dad, Obaid; his older sister, Almas; and younger sister, Fatima. Ali’s mom passed away suddenly during his first year of graduate school at Berkeley. “The only reason I got through that the way that I did is because of my faith and because of my family and the support system I have here at Berkeley, including my advisers.” (Photo courtesy of Ali Bhatti)

The only reason I got through that the way that I did is because of my faith and because of my family and the support system I have here at Berkeley, including my advisers. This is a big part of what makes me proud to be a Muslim is the fact that I can rely on something so strong, so foundational in me that it can get me through the difficulty, the pain, the real anguish of losing your mom unexpectedly while being a graduate student away from her. And that was very, very hard to do.

But as Muslims, we like to say, “Alhamdulillah.” We say, “All praises be to God.” For good and for bad, for whatever you are going through, to view it in the light of, “This is something that is a test on you and your faith and your well-being and who you are as a person.” And to have Islam as my faith and to be a practicing Muslim and to be able to use that as a means of not just coping, but growing from the most difficult part of my life, has been huge.

[Music fades out]

Anne Brice: Part 5: Muslim at Berkeley

Ali Bhatti: As a graduate student here at Berkeley, I really want to see people like me and people who are practicing Muslims like me in spaces like academia. Just mainly because there’s, especially in the world where I study, in the sciences, there’s often this tension between science and religion. But what’s weird for me is that religion and the study of science, specifically, reaffirmed my religious faith.

[Music: “Across the Table” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ali with his housemates, all of whom are Muslim. “We have this opportunity to go through this month together,” he says, of Ramadan. “There’s a whole different atmosphere that ends up coming within the house, within yourself, within the people that are practicing around you during this month. And it’s really, really special.” (Photo courtesy of Ali Bhatti)

UC Berkeley and Berkeley as a whole has a strong Muslim community, which is great. There’s a mosque in Berkeley, and that mosque has daily night prayers, as they’re called, during Ramadan.

It has been really, really amazing as a Berkeley student, mainly because of the fact that I’ve been at the same house that I’ve lived in since I came here, since 2019. We’re all Muslim graduate students, so we have this opportunity to go through this event, this month together, pray together and fast together during this month. So, there’s a sense of immediate camaraderie, an immediate sort of brotherhood, if you will, in the house itself, which has been a huge impact in my success or feeling of spirituality during this month.

There’s a different feeling, there’s a whole different atmosphere that ends up coming within the house, within yourself, within the people that are practicing around you during this month. And it’s really, really special.

Anne Brice: Ali Bhatti is a Ph.D. candidate in science and math education at UC Berkeley. I’m Anne Brice, and this is Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs at UC Berkeley. If you enjoy Berkeley Voices, tell a friend about us — it really helps get the word out. And you can follow us wherever you get your podcasts. We also have another show, Berkeley Talks, which features lectures and conversations at Berkeley. You can find all of our podcast episodes with transcripts and photos on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

[Music ends]

Listen to other Berkeley Voices episodes: