Connecting across differences can be scary. But this trans poet says it’s worth it.

"It’s about recognizing their common humanity and figuring out how to create a space where both people can exist," said Julia McKeown, a bridging project coordinator at UC Berkeley's Othering and Belonging Institute

June 13, 2023

Julia McKeown, who graduated with a master’s degree in folklore from UC Berkeley in 2022, is now a bridging coordinator for the campus’s Othering and Belonging Institute. (Photo courtesy of Julia McKeown)

It was a freezing night in rural Morocco, and Julia McKeown was huddled under a stack of blankets watching Janelle Monae music videos on their phone. It was fall 2018, and McKeown, whose pronouns are they/them, was living in a beautifully tiled, but drafty, apartment in Missour province, where they were working as a youth and development volunteer for the Peace Corps.

And it was while they were watching Monae dancing with abandon, looking incredible in a suit, that McKeown thought, “Why can’t I wear a suit?”

It was a simple, but loaded question. As a teenager, McKeown felt the way many of us have — that their body was public property, something that others had a right to comment on and control, in subtle and overt ways. McKeown often felt like they were performing the role of “girl,” one they were uneasy in, but weren’t sure why.

“I think it took me a while to figure out that I was performing gender because I was performing everything,” said McKeown.

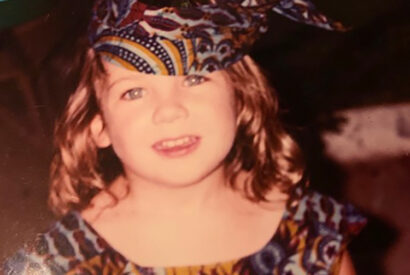

When McKeown was 6 weeks old, they and their family moved to Senegal. The family moved back to the U.S. four years later to a small town in Massachusetts. “It was a place where being weird meant being alone, being on the outskirts,” said McKeown. “I learned pretty fast not to be weird.” (Photo courtesy of Julia McKeown)

McKeown was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1994. When McKeown was 6 weeks old, their parents, both of whom worked in global public health, moved the family to Senegal, where McKeown’s dad got a job on a project with Tulane University and local partners. Four years later, they moved back to the states, this time to Ashland, a small town in Massachusetts.

“It was a place where being weird meant being alone, being on the outskirts,” said McKeown. “I learned pretty fast not to be weird.”

But it wasn’t easy. McKeown, who had spent the first four years of their life in West Africa, showed up in Massachusetts wearing vibrant, colorful clothes and speaking French and Wolof. By the time they got to kindergarten, they began to get unwanted attention for how they looked and sounded.

“I came home and told my parents, ‘I don’t want you to speak French to me anymore. Everyone already thinks I’m weird.’”

After their freshman year of high school, McKeown and their family moved to Chapel Hill, North Carolina. It was during a time in McKeown’s life when gender roles and expectations became more defined and oppressive. And McKeown found these expectations especially difficult because of their body’s size.

“I also grew up fat my whole life, and it’s still difficult for me to disentangle dysphoria and dysmorphia,” said McKeown. “As a teenager, I learned that the only way to perform gender effectively at my size was to become sort of sexualized in a really particular way because I was never going to be allowed to be desirable — and being desirable was the only thing that mattered.”

So, McKeown just kept performing. It didn’t feel good, but it was familiar.

And years later, when McKeown asked themselves, “Why can’t I wear a suit?” they realized they didn’t feel like a woman, that the gender they were assigned at birth didn’t match how they felt about themselves. It never had.

Realizing this in Morocco, though, was complicated. Same-sex relations are illegal in the country, punishable by prison time. Gender roles and spaces are strictly defined and queerness isn’t often visible in public spaces. To show a person’s queerness in public brings with it significant risk.

McKeown in 2019 at their 25th birthday celebration in Missour province, Morocco. Later, they celebrated their newly realized nonbinary identity in a quiet way: By cutting their hair short and changing their pronouns. (Photo courtesy of Julia McKeown)

So, McKeown celebrated their newfound freedom in a quiet way: On their 25th birthday, they cut their long hair short and told their Peace Corps cohort that they were nonbinary and were going to begin using she/they pronouns. Over time, McKeown became more comfortable claiming their trans identity and now exclusively use they/them pronouns.

“I really wish I had known I was trans sooner because it would have made my childhood so much more full of potential,” said McKeown. “It would have been hard in a million other ways, but my gender wouldn’t have had to be another thing that I just couldn’t get right because of things out of my control.”

“Being trans is just not, for lack of a less Gen Z word, vibing with the gender that you were assigned at birth,” McKeown continued. “It’s just looking at it and for whatever reason saying, ‘This just doesn’t feel like me.’ And it can be in the smallest ways or in the largest ways. It can be you want to change your body, or you want to change your name, or it can be that you just wish the world would stop putting certain labels on you based on the way they view your body.”

At UC Berkeley, McKeown would set out to find their community. But a global catastrophe made it harder than they expected.

Using folklore and poetry to explore queerness

A few months after they finished their Peace Corps service, McKeown came to Berkeley in January 2020 to begin their master’s degree in folklore.

Before they arrived, they knew what they wanted to study: queer narratives in Morocco. It was a topic that was more or less off limits, and yet deeply affected many of their Moroccan community members, when they were working for the Peace Corps. But here in the states and as a student at Berkeley, they could explore it more fully and in the open.

McKeown got a grant to return to Morocco and planned to research the many, more private ways that queerness is expressed in Moroccan culture and how these narratives are just as important and valid as how queerness is expressed in the U.S.

“There is a whole spectrum of queerness that exists in Morocco that is incredibly culturally tied in,” said McKeown. “There are a lot of queer Moroccans who would like to be seen and understood and get married and have parades and all of that. And there are a lot of queer Moroccans for whom being able to have a same-sex relationship that is not public allows them to have their family, their religion, their culture be a part of their lives and to have their same-sex relationship be a part of their lives, as well.

From left: Molly Robinson (left) and Kate Brock (right), friends of McKeown’s from Berkeley’s folklore program, on a sail boat in Yorktown, Virginia, in summer 2022. (Photo courtesy of Julia McKeown)

“It was really interesting to learn about this and explore what it can teach us about the way we’re talking about queerness in the U.S. We’re erasing these narratives here because we are so focused on how countries don’t accept queerness instead of looking at how queerness is shaped by the systems and cultures queer folks exist in.”

And folklore, an academic discipline that McKeown defines as a way for people to tell their own stories, would help McKeown bring queer Moroccans’ stories to life.

But just two months after McKeown’s program started, the pandemic hit, and in-person instruction on campus was moved online.

“When I showed up at Berkeley, I was looking for community and really excited to share my ideas with people,” McKeown said. “Then, I had to work through a bit of heartbreak after the pandemic made that harder to do. I didn’t feel like I was joining a community of scholars.”

A trip to Morocco was off the table, and McKeown had to figure out how to do their research from afar and how to build their own community on a sprawling campus and city under lockdown.

The isolation got to McKeown. Although they’d made a couple of fast friends in their tiny program, they felt frustrated, unable to find resources for queer students at Berkeley. So, with the help of poetry professor Chiyuma Elliott, they got a grant to come up with a list of resources that the campus offered. This led McKeown to start a poetry workshop in fall 2021 for queer and trans people on campus through the Arts Research Center called Calling the Elders. It was created in partnership with the Queer Alliances Resource Center and graduate student Drew Kiser from the Sexual Orientation and Gender Advocacy Project.

“A Call to the Elders”

Read McKeown’s poem that inspired the title of their poetry workshop.

For McKeown, teaching a poetry workshop to queer and trans people was a dream, a place where they felt most alive.

“Honestly, it was magical,” said McKeown. “I never in my life feel so much like I’m not doing work as when I am crafting a workshop.”

The workshop wasn’t about creating a grand production or performing for a big audience. Instead, it was an opportunity for people to share their own stories in a welcoming and supportive environment.

“One thing that I learned during undergrad in North Carolina was that a poetry workshop has to be an accessible space,” McKeown said. “That doesn’t mean you can’t talk about intense prose or styles, but it needs to be a place where people can show up and feel like they don’t have to be an English major to enjoy the space. Some of my biggest joys were just watching people who hadn’t engaged with poetry produce some beautiful work.”

After McKeown graduated in 2022, having earned an almost entirely “pandemic degree,” as McKeown put it, they joined the Othering and Belonging Institute as a campus bridging project coordinator.

This time, it was a role that McKeown not only wanted to engage in, but one that would challenge McKeown to develop ways to bring people together in a country known for its deep and growing divisions.

Bridging and belonging at Berkeley

At the Othering and Belonging Institute, McKeown works with a team that’s figuring out how to help individuals and groups of people who might see themselves as very different from one another to build bridges of connection between them.

“The institute notices moments when people are pulling away from each other, where they’re saying, ‘You’re not like me, and therefore we cannot build something together,’ or, ‘You are not like me, and therefore, I don’t see you as human,’ and it’s saying, ‘OK, how do we work on this?’”

The act of bridging, McKeown said, isn’t about one person proving to another that they’re wrong; it’s about recognizing their common humanity and figuring out how to create a space where both people can exist.

McKeown in March 2023 near Santa Fe, New Mexico. (Photo by Molly Robinson)

In their role, McKeown is working to scale up and make more sustainable some of the bridging workshops and events that the institute is organizing, and to help people understand what bridging is and to connect them with resources.

Although bridging, when done right, has potential to break down and rebuild systems of power, said McKeown, it can also be scary, especially for marginalized groups.

“As someone who is trans, I have really hard days with this, where I sit and I think, ‘How do I sit down and bridge with someone who doesn’t want me to exist? Who is actively trying to write me and the people I love so dearly out of existence? Who is putting us in danger? I am so afraid.’

“When I get to, ‘I am so afraid,’ sometimes, when I am well-resourced, and I have someone to hug me through thinking about these things, I can say, ‘They are also so afraid. They’re only doing these things to me because they are also so afraid.’

“It doesn’t take away from the fact that they’re using their power to hurt other people. It doesn’t take away the fact that they have put me at risk. But they’re afraid, and I’m afraid, and maybe we can start there.”

McKeown’s work in bridging, along with their poetry and research, reminds them that there isn’t a right or a wrong story or just one way to live, but that we can always reach toward building more human connection. We’re all somewhere in between, living in the liminal spaces, trying to figure out how to survive and hopefully find joy.

“That’s what fascinates me and keeps me going, is just saying, ‘We’re all a mess. Somewhere in that mess we might actually have more to talk about than we thought.’”

McKeown’s poetry workshop has continued on campus, and has expanded through the Othering and Belonging Institute under the title Poetic Bridges. The ongoing series, open to everyone, will be taught again in fall 2023 and spring 2024 by its facilitator Camille Santana Considine. McKeown will also be teaching a one-credit course, called Bridging and Belonging, during fall and spring semesters next year.

Learn more about the concepts of bridging and belonging on the Othering and Belonging Institute’s website.

Read more about the bridging project and listen to podcast episodes about bridging and belonging.